When it was time to make his way downstairs from the 78th floor of One World Trade Center, he didn’t panic.

Michael Hingson has been blind since birth. What most people consider a disability hasn’t hindered him, though, not even during that life-or-death situation. That’s because his guide dog, Roselle, was by his side.

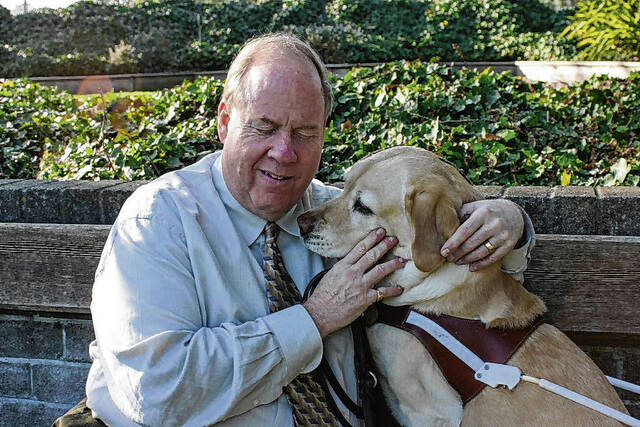

Hingson will present a lecture titled, “Labrador Lessons from a Canine Hero,” Thursday at Franklin College’s Napolitan Student Center. His current guide dog, Alamo, will join him.

“I rely on listening to what’s going on around me,” Hingson said. “I could ride my bike and hear the echoes of the tire on the road and hear when there’s a parked car in front of me. The best way to understand it is, it’s another way to do the same thing. I use auditory cues I can get. It’s sometimes a side people should use but don’t use.”

He got his first guide dog in 1964, when he was 14 years old. Guide dogs are less common for blind people to use than a cane, and there is no superior method for blind people to get around, Hingson said.

Canes rely on the person using them to interpret their surroundings to navigate, while dogs automatically avoid an obstacle, he said.

“I can teach you to use a white cane in five minutes, but the confidence to use a cane takes many months. It’s not just having it go out in front of you, but the confidence to do that and interpret information. It’s not any different than growing up and learning to see,” Hingson said.

“The school decided it would be best for me to use a guide dog. A cane is a contact device and a cane hits something and you can decide how to go around it. A dog will automatically go around things it can go around, or will stop until you give it commands to direct it.”

In 1999, Hingson got Roselle, a labrador retriever who was by his side on Sept. 11, 2001. It was the same year Hingson started working with Quantum, a California-based company centered around data storage. When the company decided it wanted an office in the World Trade Center, Hingson was called on to lead the office as the mid-Atlantic sales manager, he said.

“In the World Trade Center, I spent a lot of time learning what to do in case of an emergency. I learned where things were. As the leader in the office, I needed to be as effective in moving around the complex as anyone was. If I wasn’t effective, how could I sit at a meeting and negotiate a contract if they viewed me as less of a human being?” Hingson said.

“I needed to be able to not only be as effective, but know other kinds of information other people didn’t know but should know. Where were the emergency exits? You would rely on signs to tell you where the exits are. For me, my way of life is to make sure I know what to do in an emergency to help other people get out.”

At 8:46 a.m., hijackers crashed American Airlines Flight 11 into the side of Tower 1, between floors 93 and 99, less than 20 floors above where he was standing.

David Frank, a co-worker, was with Hingson that morning as they prepared for a seminar. When Frank saw burning paper, fire and smoke outside the windows of Tower 1, he started to panic, but Hingson remained calm and collected.

“I kept saying, ‘slow down.’ Guests were moving toward the exit to the office and David said, ‘you don’t understand, you can’t see it.’ It’s not what I didn’t understand, it’s what David didn’t understand,” Hingson said. “I understood what David did. There was burning paper and fire and smoke. But what David didn’t see was, I had a dog next to me sitting and wagging her tail and not giving any fear indication. I knew Roselle’s fear reaction. She was afraid of thunderstorms.”

With Roselle in front of him, Hingson, Frank and the Quantum seminar guests made their way down the 77 flights of stairs to the lobby. It took about an hour, he said.

“Every time we got to the bottom of a flight of stairs, I had to tell her, ‘go left,’ to the next set of stairs,” Hingson said. “The discipline I have with dogs is, I want them to wait for commands. Getting to the bottom and getting left and left and going down more stairs, it was not automatic. I still gave her commands and wanted her to hear my voice and that I was making it. If I was nervous, she would get worried and not do her job. It was important for me to keep the team focused.”

After finding his way out of the World Trade Center with Roselle, they made an appearance on Larry King Live, the first of five interviews with King.

“Along the way, I had been urged to write a book, starting in 2002,” Hingson said. “It took a while to come to fruition.”

King wrote the forward for it. The book, titled “Thunder Dog,” published Aug. 2, 2011, and became a New York Times bestseller. The book includes 10 lessons of “guide dog wisdom.” Since 9/11, he’s also given speeches around the country about his experience.

“One of the major points I try to deal with when speaking to audiences, they have a strong misconception about blindness,” Hingson said. “People can live, work and be in the world, just in a different way, just like how left-handed people do things in a different way.”