Indiana Army National Guard 1st Sgt. Joseph Stringer remembers the first plane that landed at Indianapolis International Airport last year filled with Afghans fleeing their country as the Taliban rushed back into power.

As he grabbed his bullhorn, an Afghan who spoke English instinctively reached up for it, expecting to be needed to translate.

But there was no need. Stringer, a Greenfield resident and Greenwood native, addressed the group in perfect Dari, a language spoken throughout Afghanistan.

He and his unique skill were part of the mission that processed thousands of evacuees at Indiana National Guard Camp Atterbury in September 2021 following the War in Afghanistan. It’s just one of the ways he’s used his language abilities throughout his service in the National Guard, an experience that’s taken him across the world in a variety of roles and shaped his perspective of humanity.

‘Volunteer for everything’

The 40-year-old grew up in Greenwood and has lived in Greenfield with his family since 2013.

Stringer enlisted in the Indiana Army National Guard in 2000 while still in high school. As he was contemplating that decision, he called his cousin, a U.S. Army recruiter, in search of counsel. His cousin gave him two pieces of advice. One was to never let his drill sergeant know his name during basic training. The other was to volunteer for everything.

“You’re going to wind up doing some things you don’t like, like cleaning bathrooms and scrubbing toilets,” Stringer recalled his cousin telling him. “But you’re also going to get to do cool stuff because you volunteered to do the not-cool stuff. I’ve done a lot of my career based on the fact that where there was a need, I volunteered to go do it.”

He’d already had a passion for foreign languages and cultures, having lived in Spain between his junior and senior years of high school. Stringer came into the Guard wanting to do something with languages, so he started out in a military intelligence role that required him to be fluent in another tongue. He wanted to go to the Defense Language Institute to learn Arabic, but his proficiency in Spanish already checked a box needed for his position in the Guard.

In 2004, however, while studying at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Stringer and his Guard contemporaries received an email asking if any of them were interested in what would be the first-ever yearlong Dari language course at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California. Stringer didn’t know what Dari was, but he knew he’d always wanted to go to that school. He was single, could pick up and move easily, and a year in Monterey didn’t sound so bad either. So he replied in the affirmative.

“I never thought it would lead to all the other different opportunities that open up after that,” Stringer said.

An in-demand skill

To learn a new language, one has to think creatively outside the constructs of their own language, Stringer said.

“You have to be willing to break your rules in order to learn someone else’s,” he said.

Throughout his military service, Stringer has also picked up Farsi and Tajiki — Persian languages closely related to Dari. He knows some Pashto too.

“There is a logic to how languages are structured,” he said. “One of the things I love about Persian is everything has a root to it, a root idea or concept.”

By the time Stringer was studying Dari, the Sept. 11 attacks had happened and the U.S. was at war in Afghanistan and Iraq.

He recalled being young and naive at the time about where his service would take him.

“I’m in the Guard, right?” he remembered thinking. “I’m not going to get deployed. It’s one weekend a month and two weeks in the summer.”

But he had orders to go to Afghanistan before he even finished the language school. Two weeks after graduating, Stringer was in Kabul, going on missions and speaking with Afghans.

“Having that immersive experience, it really developed my fluency,” he said.

Stringer would go on to return to Afghanistan twice throughout his National Guard service, and he served in Kuwait as well. In 2018, he cross-trained in Japan with members of the country’s ground defense forces.

Lone linguist

Last year, Stringer was working for a program at Camp Atterbury as an observer and evaluator for military exercises. He was getting ready to transition out of full-time Guard work and pursue a civilian career as a paramedic when he got a call that he was needed at the camp. Stringer had a feeling what it was about, having been keeping up with what was going on in Afghanistan as the regime the U.S. had removed from power 20 years earlier quickly recaptured the capital.

“I devoted over a decade of my life to understanding that conflict, so to see everything unraveling is very shocking,” Stringer remembered.

He learned he was the only Afghan linguist at Camp Atterbury.

“I don’t think anybody planned it that way,” he said. “It just so happened Camp Atterbury was selected to be one of the host facilities, and there was an Afghan linguist on Camp Atterbury already there. And I don’t think anybody realized it, that’s not why they selected Atterbury, but what are the odds of having an Afghan linguist in the middle of Indiana?”

Soon he and his fellow service members were welcoming Afghans fleeing their quickly changing homeland.

“They had a really good team of people that really wanted to help take care of people that were having not just the worst day of their life, they were having the worst month of their life,” Stringer said. “We had a team that really worked around the clock constantly.”

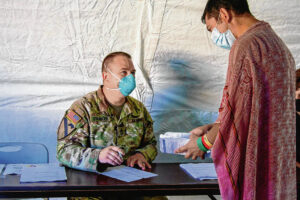

Stringer drove back and forth between Indianapolis International Airport and Camp Atterbury for about five days. He estimates several thousand Afghans arrived in that time period. Stringer would catch some sleep in his car between flights, which landed about every couple hours. Speaking in Dari through intercoms for passengers on commercial airplanes and through a bullhorn for passengers on military aircraft, he welcomed the guests to Indiana and explained what would happen next. Soldiers would help with their luggage and get them onto buses, he’d tell them, which would take them to Camp Atterbury, where they’d have food, shelter, clothing and representatives to help them from the defense and state departments as well as the Red Cross.

“I understood that for Afghans, sharing your home is an honor, especially for someone in need,” Stringer said. “So I couldn’t be more proud to have the opportunity to share my home, and so that’s something that I really wanted to make sure that every single person that came understood — I’m not happy that this happened, but anything I can do to make this experience better for you, I’m going to make sure that I try to do it, and we all are because that’s why we’re here.”

‘Huddled masses’

Stringer remembered one cold and rainy night when a military plane’s rear door came down, revealing the Afghans who were sitting in seats but also on the floor close together. A passage of the poem accompanying the Statue of Liberty immediately came to mind.

“That classic American ‘Give me your … huddled masses (yearning to breathe free),’” he said. “And I’m like, this is exactly it. This is what we stand for as a community and as a broader American people. That was extremely moving to me to be there and see that.”

He also recalled an Afghan of a recently landed flight on a Friday, the Muslim holy day, asking him if they could pray as the sun was coming up before heading out for Camp Atterbury. Stringer and his fellow Guard members were happy to wait, and he helped them determine which direction to face toward Mecca.

“You had an entire team of people who understood that this entire mission says everything about who we are as a people, from small things like that to the larger things of building that structure and making sure the medical care is there, and making sure there’s a process identified to getting people built into the right communities,” Stringer said.

Stringer remembered helping one of the Afghan guests pick up the spilled contents of their suitcase that had opened. The luggage was filled with photographs.

“Everything that meant the most to them in the world was with them,” Stringer said. “They didn’t bring clothes, they brought pictures, because they can’t get those back.”

He later helped at a clinic set up at Camp Atterbury by explaining to the Afghan guests the vaccinations they’d receive and information about medical screenings. Stringer, whose National Guard service by that point had trained him in his growing passion for health care, eventually took a civilian position at that clinic as a paramedic.

He currently serves in the C Company 2-238th General Support Aviation Battalion based in Gary, through which he maintains his capability as a helicopter medic. Stringer also works full time as a community paramedic for an Indiana University Health pilot program on Indianapolis’ east side traveling to homes of mobility-restricted Medicare patients for primary care follow-up appointments.

While serving in the clinic at Camp Atterbury, the Afghan guests would often ask him what the U.S. is like and where they should live. While Stringer knew many would likely end up in Afghan enclaves like Fremont, California and Alexandria, Virginia, he’d tout Indiana whenever he could, including its job opportunities.

“There’s so many questions and so much uncertainty out there on that road ahead of them, that I can only hope that we added that level of normalcy while they were here in Indiana that helped set them up for success when they move on to wherever they’re going to become Americans,” he said.

Story by Mitchell Kirk (Greenfield) Daily Reporter.