Every story was another treasured piece of a life well-lived.

When Valerie Stewart first started visiting Ruth Haynes as a volunteer for Main Street Hospice, she quickly felt an connection. The way that Hayes, a patient with the hospice, spoke and laughed drew Stewart closer. The pair would sit together, and Hayes would tell stories from her life.

The tales were fascinating, so much so that Stewart asked if she could record them.

“It took 20 to 30 minutes to realize I was going to learn so much from this woman. I just wanted to celebrate her, because she is extraordinary,” she said. “Even though I wasn’t thinking at all about this kind of project, I thought this was something I could do, a way to serve that family. Who doesn’t want to read their family’s stories, especially generations later?”

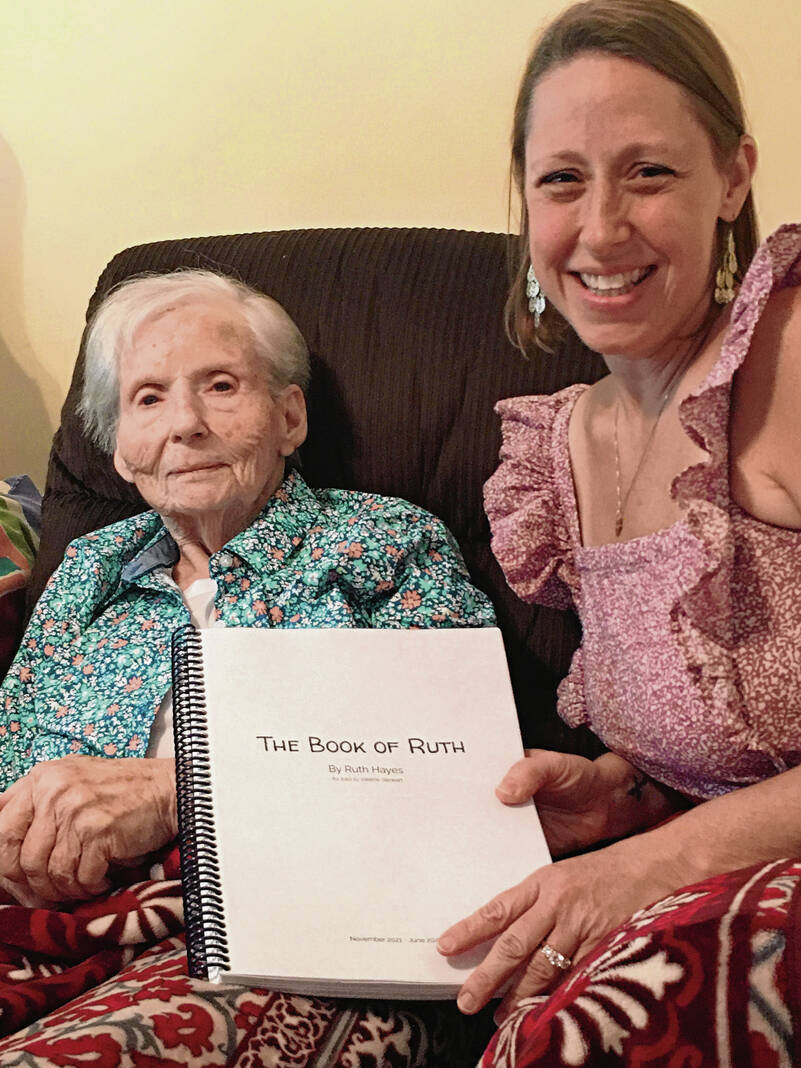

Those stories became “The Book of Ruth,” a writing project that Stewart compiled from November to early this year. At more than 100 pages long, the book offers glimpses into Hayes’ life, from childhood to now. The pages are filled with witticisms and advice, including poignant realizations as she recognized her life drawing to an end.

Photographs from the years add a visual element to Hayes’ stories.

Stewart was able to present the finished copy of “The Book of Ruth” in early June — right after Hayes’ 83rd birthday. Though her health is failing, the collection represents her legacy, and provides a history that her family can cherish forever.

“It’s going to be something the grandkids can read when she’s gone. It’s a passed down family legacy there,” said Kathy Kephart, Hayes’ daughter. “When Valerie brought that up, we said, yeah, by all means, get them down now while she still remembers.”

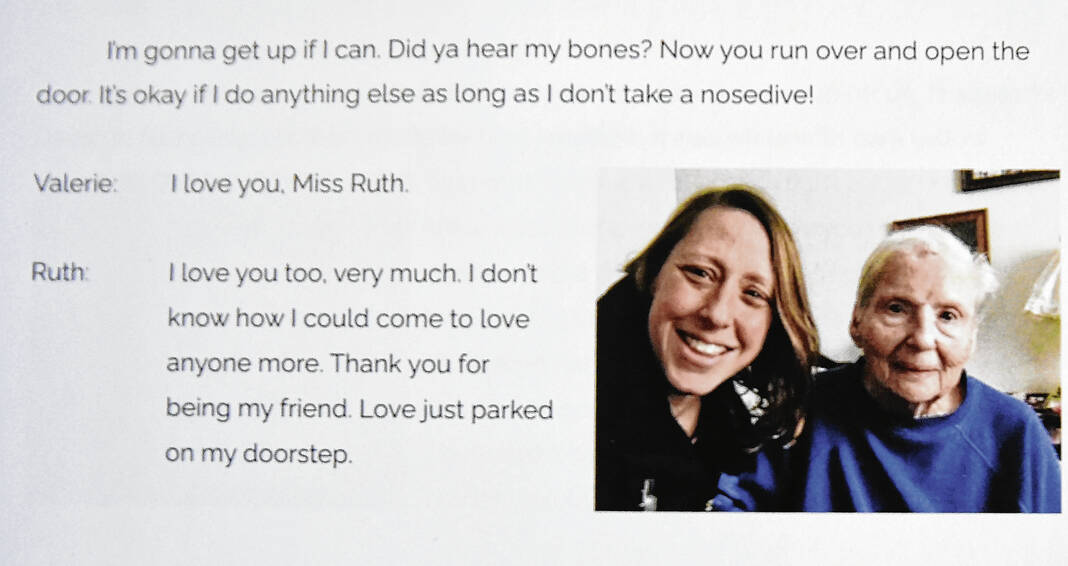

Outside of an introduction by Stewart, the book is entirely Hayes’ own words, even capturing the idiosyncrasies of her speech. That was important; Stewart wanted her family to be able to hear her voice when they read it.

“I told her, you’re the author now. You tell me what you want me to write. I’m the humble secretary and I’ll write it just the way you say,” she said. “One of the triumphs of this book is her unique way of speaking and describing things. It pulls you in, right away.”

So many of the stories tell of good times: hi-jinks with her siblings growing up, her kids flying airplanes made of paper and wooden clothespins, family vacations down south.

Others talk of more difficult times. One of the stories recounted the death of her husband, Rex. She spoke about how they went to the hospital to treat a diabetic wound in his ankle.

After being cleaned up, they were on their way out when he collapsed. He was killed by a blood clot.

“She was honest about the heartbreak in her life, but she was always ready to look at the positive and laugh her way through life,” Stewart said.

Stewart first signed up to be a volunteer with Main Street Hospice in September 2021. She wanted to be of service to patients and families going through times of illness and grief.

“Of all of the times that someone needs love and support, isn’t it at those times, of anticipated grief and stress and anxiety that exhaustion, that it’s needed?” Stewart said.

During her first few months as a volunteer, she would visit with different patients sporadically. But Hayes was the first patient who she saw on a regular basis.

Hayes, who lives north of Franklin, has been a patient of Main Street Hospice for about a year after being diagnosed with multiple cancers.

From that first meeting in November, Stewart was charmed by Hayes vigor and perfectly timed stories. Not 30 minutes into their introduction, she asked if she could record their conversations and stories.

“I don’t know how the universe conspired to get us together, but I’m so, so glad it did. I probably never would have met her otherwise,” she said.

From that point forward, the pair would meet every Monday. They would talk for two of three hours, with Hayes telling the stories and Stewart hanging on her every word. They also went through old photo albums, to find photos that corresponded with the stories.

Once their meetings were over, Stewart would rush home to type up their conversations.

“There are many parts, where they could find the photo album we were talking about, and they could literally hear her play-by-play of every photo. They could go through in order so they knew exactly what she felt and what she remembered from each of those stories,” she said.

Many of the stories recounted her childhood. Hayes told about her hard-working mother who was a cook at the Masonic Home, and she loved a good practical joke. Once, she hid Hayes’ father’s false teeth in the freezer as a prank.

Hayes also shared tale after tale of her kids growing up.

One was about the time her son, David, put her daughter. Kathy. in a big cardboard box, and set her afloat in their family farm’s pond.

“The old box is comin’ apart, an’ she was screamin!’ An he’s standin’ on the side just laughin!’ She’s only about three years old! I make him go get ‘er,” Hayes said.

The most moving aspects of the book come as Hayes acknowledged her remaining time left and the cancer overtaking her body. She won’t sit and cry about her situation; God wants her to use her optimism and sense of humor to help others.

And she included a message for her own children.

“This is what I want to say to my kids: don’t worry. Be yourself. And don’t worry about me. Because I seen my road. I’m going to a good place. I hope they will know that I loved them well. They’re both like me,” Hayes said.

During the conversations, Stewart made it clear that this was Hayes book; she could do with it whatever she wanted. Initially, the plan was that they would keep writing until she couldn’t tell stories anymore, and then Stewart would have the book bound to present at Hayes’ funeral.

But during the spring, after Stewart presented what she had compiled up to that point, Hayes began talking about sharing the book while she was still alive.

“So I printed it up, and took that to her. She was just tickled about that,” Stewart said. “It became clear at that point she wanted her family to enjoy it while she was still with them.”

The rough draft of the stories became the talk of the family, and any time people came to visit Hayes, they asked to see it. They’d just laugh and laugh, Stewart said.

Hayes’ health had declined over recent weeks, and Stewart wanted to present “The Book of Ruth” to her and her family while she was still well enough to enjoy it. She chose the day after Hayes’ birthday, June 5, to do so.

During a small birthday party at the hospice, the bound book was given to her and her family.

“We were amazed, simply amazed at everything that was there. There were some things that I had forgotten about, and some things I didn’t even really know about,” Kephart said.

Since that time, the books have been passed around from person to person enjoy and revel in the memories.

“Anyone who comes in wants to borrow it. I’ve heard so many times they come in and just read it through, 115 pages. They can’t put it down. They laugh and they cry, and that’s exactly what I do with it,” Stewart said.

With the experience she’s had with Hayes, Stewart wants to help other hospice volunteers compile stories from their patients as well. She spoke to a group of Main Street Hospice volunteers earlier this year, sharing tips on how to approach it and the best way to put the stories together. She described how to respect and honor the patient, protecting their vulnerable talk while being true to the project.

She also intends to stay in contact with Hayes and her family for a long time.

“They’re just such a special group of people,” she said.