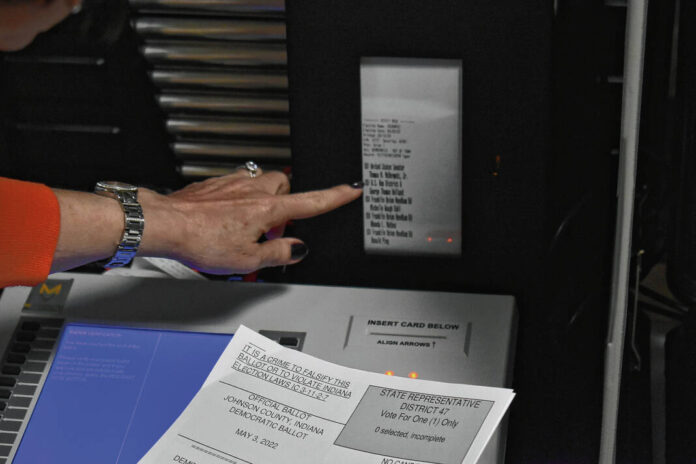

Michelle Ann Graves, a proxy for Phil Barrow, a Republican member of the Johnson County Election Board, casts a sample ballot during a public test of the county’s election machines in the basement of the Johnson County Courthouse in March. The test included the VVPAT (Voter-verified paper audit trail) system.

Daily Journal File Photo

A concerned citizens group has expressed concerns about how Johnson County residents voted in 2020, but election officials say the county’s systems are secure.

Members of Indiana First Action, a grassroots citizen group whose mission is to ensure that Indiana’s elections “represent the will of Hoosiers.” The group, which was formed in July 2021, uses “evidentiary analysis” to “discover the truth” about Indiana’s elections, according to the group’s website.

The Johnson County Voter Registration office has been receiving many public records requests for Vote Cast Records, also known as Cast Vote Records, including from Indiana First Action. The record lists a person’s voting history for a particular election.

Along with members of Indiana First Action, at least one other individual has come into the county’s voter registration office asking for a copy of these records. However, the county cannot give out that information, as it is considered by the county’s election vendor, MicroVote, as confidential, Johnson County Clerk Trena McLaughlin told the county’s election board on Aug. 29.

State officials also say the record is considered confidential, citing Indiana law regarding keeping ballots confidential, according to Indiana First Action. The group disagrees with this assessment, saying that they are not asking for the actual ballot itself, but for a report that could allow the group to “see trends in tabulation that may look awry,” according to a press release on the group’s website.

“It does not in any way encroach on the secrecy of any voter,” the press release said.

A few weeks ago, McLaughlin, members of the county’s voter registration office, along with a clerk from Knox County, took part in an hour-and-a-half meeting with Indiana First Action where members of the group expressed concerns about how elections are run with voting machines, McLaughlin said.

“They think that we need to be voting on all paper ballots. They don’t want us using the machines,” she said.

The group has been traveling across the state to ask questions about elections, however, several county clerks have refused to talk to them, McLaughlin said.

Members of the group later verbally asked election officials to keep Johnson County’s 2020 election records for a longer period of time. The county’s 2020 voting records were scheduled to be destroyed this month, McLaughlin said.

Per Indiana law, the county is required to keep records from each election for 22 months. These records include boxes of absentee ballots and papers printed from VVPAT, or voter-verified paper audit trail, systems, she said.

During the Aug. 29 meeting, McLaughlin recommended that the county keep the records for a longer period of time, saying there is no reason why the county couldn’t keep the records longer.

“I think we all want to let the public know that our elections are fair,” she said. “There was nothing illegal with them, so I don’t have a problem keeping those records.”

Later, McLaughlin recommended that the county keep the records until the end of 2023. Kevin Service, the Democratic representative for the election board, made a motion based on McLaughlin’s recommendation, which was unanimously approved.

Members of Indiana First Action also gave county officials several records they wanted election officials to research where someone may have died and they were still showing up on voter rolls.

For some of the records, members of the group went door-to-door and asked people if they voted on Election Day in 2020. The person said yes, but when the group pulled up the records on a portal that allows public access, it showed that they took part in Early Voting, McLaughlin said.

McLaughlin said that the reason why the person answered this way could be because when people vote early, they think of the day they voted as Election Day. For example, the county has early vote centers leading up to Election Day, and it’s possible a person could have voted on a Saturday and thought it was Election Day, she said.

Another factor is the period of time that has elapsed since the 2020 election.

“They just went out and did this canvassing the last couple of months,” McLaughlin said. “So (the election) was two years ago. Most people are not going to remember the day they voted or even where they voted.”

Phil Barrow, the Republican Representative for the election board, doubted that this was an issue. He said that he’d trust the voting record better than someone’s memory of how they voted two years ago. Sometimes people get confused, Barrow said.

County election officials also discussed the VVPAT system with members of Indiana First Action. VVPATs, which print off a receipt that shows how a person voted onto the voting machine, may show the person’s vote record, but members of the group told McLaughlin they were concerned that the vote was not actually being logged onto the machine, she said.

The records are being logged onto the machine, and all VVPAT records are kept by the county, McLaughlin said.

McLaughlin believes that the public records requests are going to continue for the foreseeable future, and officials want to be as open as they can.

“I feel like I can let them know that our elections are secure and we will do everything we can to help them,” she said.