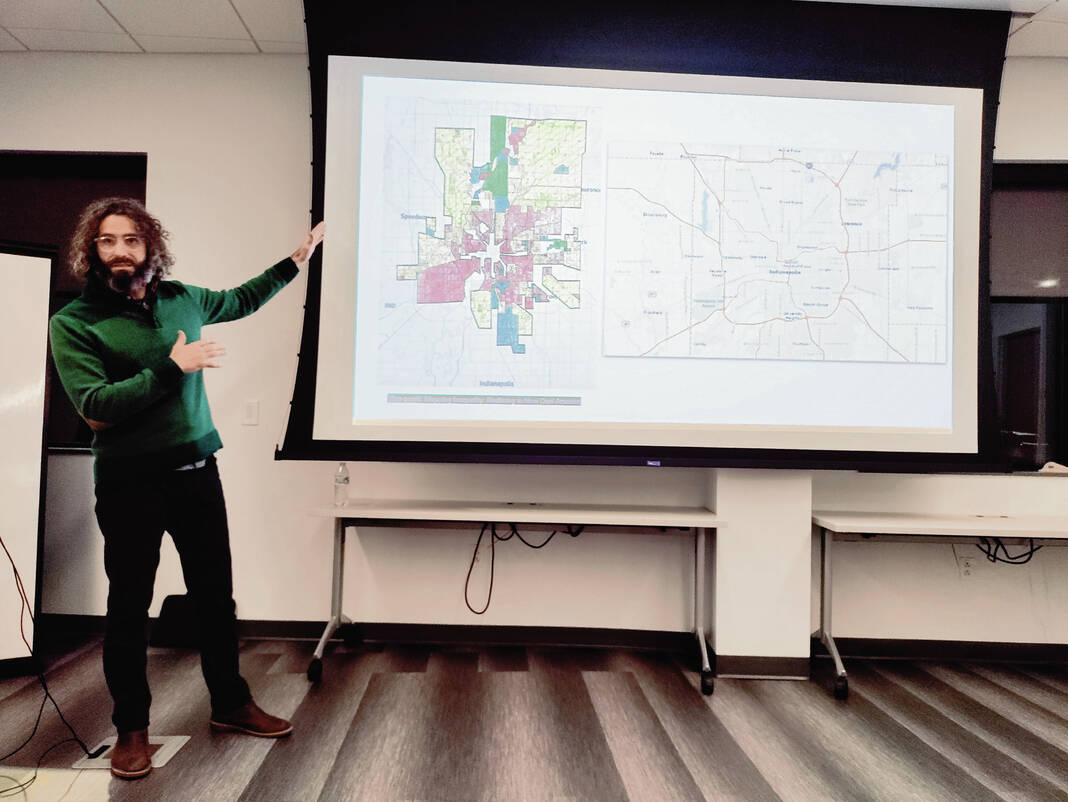

Public historian Ben Clark discusses redlining during a lecture about white privilege and environmental racism Tuesday at the Clark Pleasant library branch.

ANDY BELL-BALTACI | DAILY JOURNAL

The Clark Pleasant branch of the Johnson County Public Library hosted a talk Tuesday on environmental racism, white supremacy and their impacts on predominantly Black neighborhoods in Indianapolis.

Public historian Ben Clark, a graduate research assistant for the IUPUI Arts and Humanities Institute, delivered the talk, titled “Building Bridges: White Supremacy and Environmental Racism.” The talk, which about 20 people attended, was part of a series of lectures Clark has given for almost a year around central Indiana and as far as Richmond and Lafayette, but was his first appearance in Johnson County.

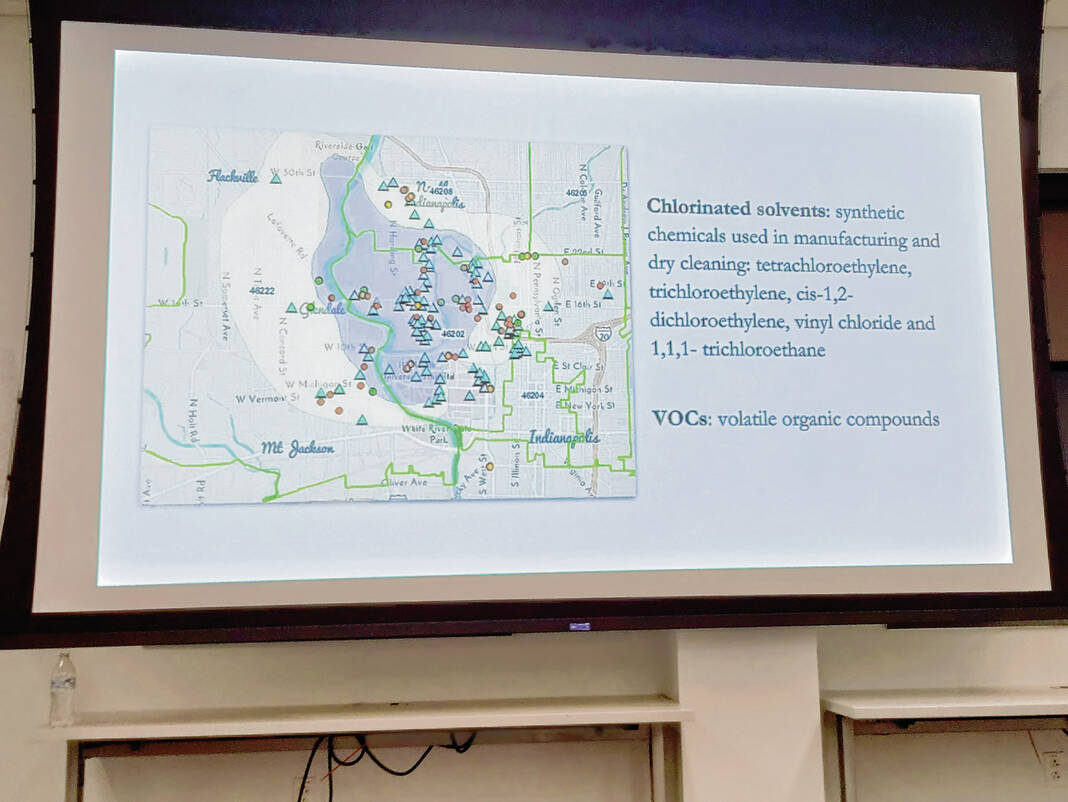

During his lecture, Clark discussed the impact of environmental negligence on two predominantly Black Indianapolis areas: the Martindale-Brightwood and Riverside neighborhoods. In Riverside, chemicals from dry cleaners contaminated the groundwater, resulting in a high level of chlorine solvents in volatile organic compounds. Even when the water was declared safe for drinking, the risk of vapor intrusion through crawl spaces in basements remains, Clark said.

In the Martindale-Brightwood neighborhood, the American Lead smelter factory was a location for reclaimed lead in car batteries from 1946 to 1965. While many former white residents were able to move out of the neighborhood because of incentives from the G.I. Bill, which was created in 1944, Black World War II veterans were often denied the ability to move into the same suburban neighborhoods because of discriminatory housing policies, meaning a significant number of Black residents had to stay in neighborhoods like Martindale-Brightwood, even as lead contamination affected their health, Clark said.

“White privilege meant white people could move out, but Black people stayed behind,” he said. “The lead smelting factory came and operated for 20ish years, caught fire and then could no longer operate. American Lead pulled up stakes and left, but there were still tremendous amounts of lead pollution in the soil.”

The lead remained in the soil for decades until 2005, when the Environmental Protection Agency required the lead company that owned the smelter to excavate tarnished soil from about 220 homes.

Beyond the two neighborhoods, an even larger swath of Marion County has been affected by redlining, a practice that started in the 1930s, for which government and real estate officials would highlight certain neighborhoods in red as a hindrance for development because those areas were deemed as undesirable. Those neighborhoods were often predominantly Black. Redlining also led to the practice of building interstates through low-income neighborhoods, which can be seen in Indianapolis. Before lead was banned from fuel in the 1990s, leaded gasoline particulates would shower down from the interstates onto those poor Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, causing contamination, Clark said.

“For red areas, you wanted to say away from those. They were not a good investment because that’s mostly where the lower-class Black people lived. This is the type of language they used on these government documents,” he said. “These are areas the interstates run through. These neighborhoods have been decimated by the interstate, and that’s how the lead got there for the most part.”

Along with being knowledgeable of environmental racism and its effects, it’s important to try and change things for the better through advocacy, said Karen Lunsford, a Greenwood resident who attended the lecture.

“Every person who is concerned about the environment must keep the issue in front of our legislators. Petroleum and chemical corporations as well as corporations that use harmful chemicals in their businesses have a big influence on congress and legislators,” she said. “As we are approaching the start of a long legislative session, we must be vigilant about what is happening the legislative committees. Everyone concerned about the short and long-term effects on the environment must keep the issue in front of the Indiana legislature.”

Clark recommended attendees call lawmakers and get friends to do the same when they are concerned about a bill so legislators know the potential effect on their constituents.

John Kooi, also a Greenwood resident, discussed the importance of voting.

“I came just because I’m interested in the health of the state. I moved here four years ago and I’m starting to collect information about where Indiana ranks in important issues like air pollution and groundwater pollution,” Kooi said. “More people should pay attention to that kind of stuff when they head to the polls. It’s more about people than about statistics.”