Upstream Prevention Project Coordinator Erica Ratz holds up a NARCAN nasal demonstration device during a Layperson Naloxone Training at the Johnson County Public Library’s White River Branch Thursday.

Noah Crenshaw | Daily Journal

Opioid overdoses happen every day, often without catching the public’s attention.

Time is critical when responding to these overdoses, so a local public health organization has been hosting trainings to teach the public about what to do in these situations.

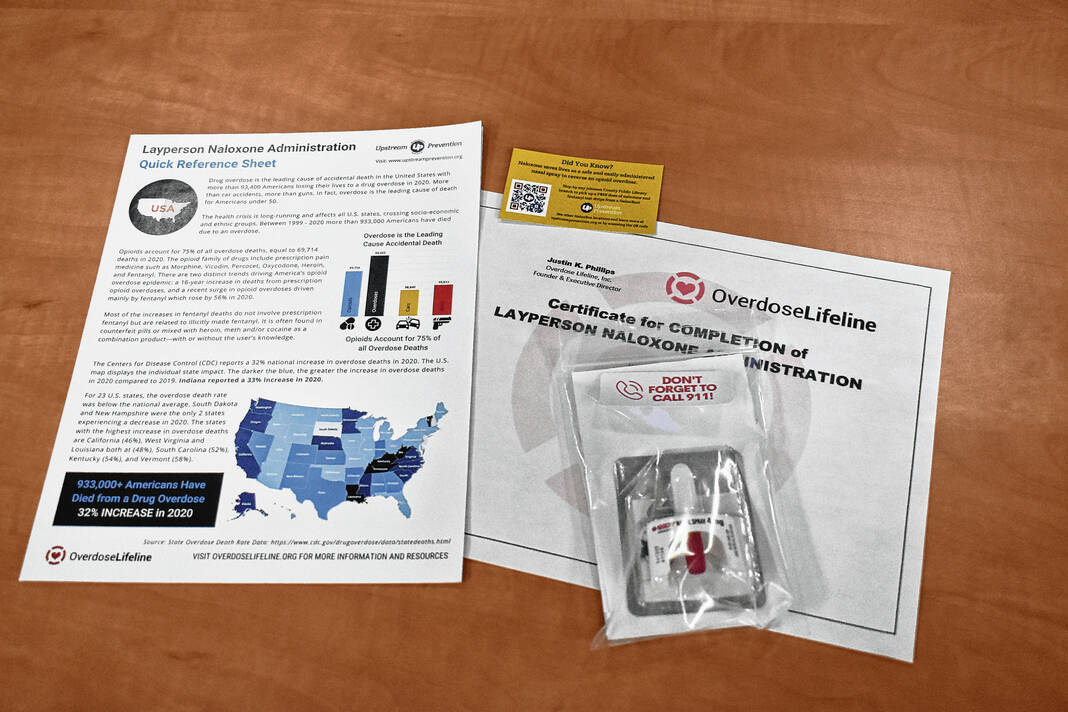

Upstream Prevention has been holding Layperson Naloxone trainings to teach residents facts about addiction, how to recognize the signs of an opioid overdose and how to administer the opioid overdose reversal drug Naloxone, also known as NARCAN. At the conclusion of the training, attendees are given certificates and receive a free dose of nasal Naloxone as part of an overdose rescue kit.

Substance Use Disorder, often referred to as addiction, is a chronic brain disease that causes someone to use a substance uncontrollably despite its harmful consequences. It’s an illness that can affect everyone, regardless of race or socio-economic status.

“It affects all walks of life. Anybody can become addicted,” said Kaleb Lane, a peer recovery coach for Upstream Prevention.

The illness often leads to someone to overdose, which often leads to death. For the last decade, overdose deaths have been continually increasing across Johnson County, Indiana and the United States.

In 2021, there were 108,000 deaths across the U.S., said Erica Ratz, a project coordinator for Upstream Prevention. Locally, Johnson County reported 40 overdose deaths in 2022, a slight decrease from 45 deaths the year before, according to the Johnson County Coroner’s Office.

On Thursday, Lane and Ratz facilitated a training at the Johnson County Public Library’s White River Branch, which was made free through a partnership between the library and Upstream Prevention. They addressed common myths about opioids, overdoses and Naloxone.

For example, one common myth is that fentanyl or fentanyl analogs are resistant to Naloxone. This is not true as Naloxone is designed to specifically respond to opioids, including fentanyl, Lane said.

“If someone’s not responding to Naloxone, it may need more time, you may have to wait two to three minutes and administer another dose,” he said. “More than one dose may be needed after the person has been without oxygen for too long.”

Another myth about fentanyl is that someone can overdose just by touching it. In reality, it has to be introduced into the bloodstream or through a mucous membrane in a nose to feel the effects, he said.

The duo later discussed the role of harm reduction in the opioid public health crisis. Harm reduction has been utilized outside the opioid crisis, and other outside examples include bicycle helmets and sunscreen, Ratz said.

For the opioid health crisis, Naloxone is an example of harm reduction, along with fentanyl test strips, medication-assisted treatment and syringe exchange programs. Education, along with access to support services are also examples of the harm reduction philosophy, she said.

Lane and Ratz also explained the common signs of opioid misuse and overdoses. Some signs of misuse include covering arms with long sleeves to hide track marks, an unhealthy look and constricted pupils. Environmental factors include spoons with burn marks, along with aluminum foil or gum with burn marks, Ratz said.

Signs of overdoses include paleness, limpness, or blue fingernails and/or lips. The person can also feel clammy or cold to the touch, Lane said.

If these signs are present and the person is overdosing, people should call 911 first before using Naloxone. This is because the drug often lasts longer in the body than the Naloxone, and a person could re-overdose without medical treatment, Ratz said.

“Once the Naloxone wears off, a person can start to re-overdose again,” she said. “That’s why it’s always really important to call 911 and get them to treatment.”

It is impossible to overdose on Naloxone, so using it multiple times is allowed, Ratz said.

“There are some people who, unfortunately because the fentanyl is getting stronger in the community, have taken four or five Naloxones to revive them,” Ratz said.

Additionally, if the person isn’t actually suffering from an opioid overdose, the use of Naloxone is still safe. It does not cause adverse effects on people who are not overdosing, Ratz said.

When someone is overdosing, people should make sure to turn the person on side in a recovery position. The person could vomit after Naloxone is used, and this will help keep their airway clear, she said.

Trainings like this are important for the public to take part in because you never know when this could happen, Lane said.

Some people can show clear signs of addiction, while others, like young adults, can just be experimenting with a drug when they overdose. Parents being able to recognize the signs of an overdose and having Naloxone on hand to provide first aid while you wait for first responders can be life-saving, Lane said.

“It’s just adapting to the world we live in,” he said. “So I would rather have it and not need it than need it and not have it.”

Taking part in layperson Naloxone training is similar to taking part in CPR or First Aid training, and it has the same goal: being prepared to help others in the community. It also helps reduce the stigma around addiction/substance use disorder by educating the public about the issue and how to respond to it, Ratz said.

“The more we talk about it, the more people feel comfortable to seek treatment,” she said. “If (an overdose) does happen, to know how to respond, I wouldn’t want feel helpless in that kind of situation and I’d be able to help one of my neighbors or friends.”

Ratz hopes this stigma will eventually fade away like the stigma around mental health has started to. Substance use disorder is a chronic illness, and not a choice people make, she said.

“It’s not a weakness. It’s not some kind of a moral failing,” Ratz said. “It is a disease, and we should learn how to help other people.”

For more information on the trainings or to schedule one, people can visit UpstreamPrevention.org or email Ratz at [email protected]. Trainings can be scheduled for free.