School is back in session in southern Johnson County.

Inside the sturdy brick walls of Union Joint Graded School No. 9, former classrooms will become bedrooms, sitting rooms and kitchens. Wood floors have been revealed, and ceilings have been removed to fix beams and joists. A leaky roof has been fixed and the foundation has been waterproofed, among dozens of other smaller projects.

Stacie Grissom and her husband, Sean Wilson, knew that fixing up the old school building, which sits halfway between Nineveh and Franklin, would be a challenge. They were not discouraged.

“Restoring things is a lot harder than building things new. It means a lot to have something with history,” Grissom said.

For the past year and a half, the couple — with the help of family — have been transforming the former school-turned-home. The project is ongoing, with hopes for the couple and their two children, Arlo and Margot, to move in later this year.

Their vision for the historic building is grand, with redone bedrooms for themselves and their children, a raised patio for entertaining, and spacious central rooms filled with natural light from dozens of windows.

The opportunity to carry on the history of the school has sparked excitement in the family.

“Everyone around that area has some story about the school. They all had ancestors who went there, or it’s part of their childhood or young adulthood. If it had been torn down, a lot of people would not be happy,” Wilson said. “So it’s cool to keep it alive.”

The pair are both Johnson County natives, who grew up in the Hopewell area and attended Hopewell Elementary School.

Since 2012, they had lived in New York City. But they had always dreamed of moving back to the Midwest at some point.

“As we got older and older, the Midwest became Indiana, and then, oh, maybe Bloomington. Then we had a baby in 2021, and I woke up one day and said, ‘I want to move back to Franklin. I want to be by my family,’” Grissom said.

Searching for a house in the area, they were interested in something unique to work on. Their real estate agents, Hemrick Real Estate, suggested the old Union Joint Graded School No. 9, a building Grissom remembered from her childhood.

“In the email subject line, (our real estate agent) said, ‘Don’t judge me.’ He knew we wanted something quirky, but he thought this was too quirky,” Grissom said. “I sat up straight and started calling my mom. And we bought a school.”

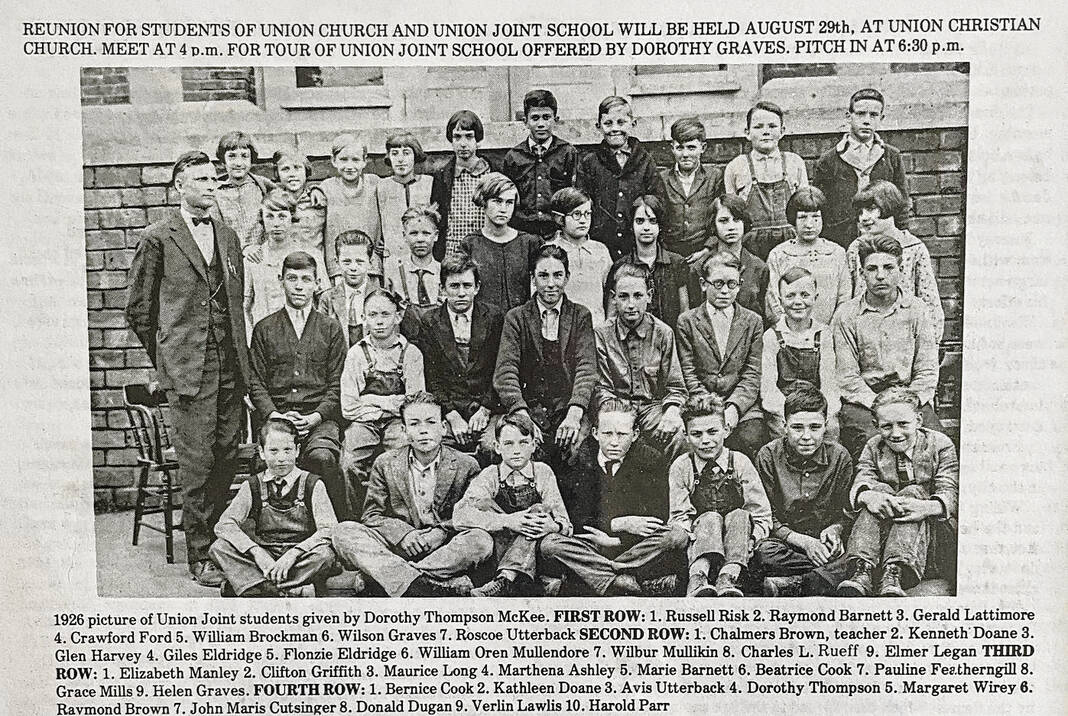

Union Joint Graded School No. 9 had been built in 1914 along County Road 300 South to accommodate children in far-from-town areas of both Nineveh Township and Franklin Township. The idea was to bring students together in a multi-grade building, which would give them a better education than a single-room schoolhouse.

Use of the school was discontinued in 1935, when it was determined that it was too expensive to operate. The structure was purchased and used for apple storage, then passed to another buyer. For a time, Rural Youth used it to conduct its meetings. In 1956, it was purchased by Dorothy and Charles Graves, who turned it into a two-apartment home.

“Charles was thrilled to death,” Dorothy Graves, a former student at the school, said in a 1999 Daily Journal story. “But the place was a mess when we came.”

Graves lived in the schoolhouse apartment for most of her adult life, and one of her daughters and son-in-law lived in the other apartment.

So the structure had already been transformed into a living space.

“It’s a big building to take care of, and we’re really thankful they kept it alive, because so many of those types of buildings aren’t here today. It’s here today because of them and the community around them that it’s still here,” Grissom said.

But that doesn’t mean it was ready to move in when the couple purchased it. The roof needed to be replaced. Floor joists throughout the structure needed to be fixed. Excavations around the foundation were required to make additional repairs.

Work started almost immediately. With the couple still living on the East Coast, they relied on family, including Grissom’s parents, who work in commercial realty. They could help identify what work needed to be done, and serve as a contact point with contractors as the project gained momentum.

“It’s hard enough if you’re actually there with a huge project like this. Obviously, doing it remotely is even more challenging. But we’ve had a lot of support from family,” Wilson said.

Still, even with the work needed, the house has enchanted the couple. They’ve been particularly enamored with the windows — rooms are laden with 96-inch windows all the way around, with some as tall as 118 inches. So much natural light will add to the airy atmosphere in the home, Grissom said.

Though artifacts from its schoolhouse days, such as chalkboards, are gone, they are trying to save as many unique architectural elements as possible.

“We were worried we’d have to replace a lot more of the floors, but we think we can save half of them. You just can’t get floors like this anymore,” Grissom said. “We’re excited about the basic structural elements.”

Other aspects will pay homage to the building’s past. They hope to use black tiles in the kitchen as a backsplash, approximating the chalkboards that were once there. Other tiles from the early 20th century will be implemented into other rooms.

“When you’re making style decisions, it’s fun to have a narrowed scope, creatively,” Grissom said. “We can brainstorm on things that were used in municipal buildings around the turn of the century and use them in the house.”

With help from Danny Causey, director of historic preservation at conservation group Franklin Heritage and Madison Street Salvage, they put together renderings of what the kitchen, front entrance and other areas of the house would look like.

A plan came together about converting the schoolhouse to their needs, Wilson said.

“We have to change the internal layout, because a four-room schoolhouse isn’t conducive to actual living. But the facade is one of the things that will remain intact,” he said.

The family plan to move back from Philadelphia to Franklin in May, after Wilson completes his medical residency there. They’ll be staying with their parents until the building is livable.

As work has continued, the couple has let their enthusiasm for their new home grow. Grissom started an Instagram account and blog following their journey.

They’ve crafted a logo for their new “school,” complete with a mascot, the Gobblers — a nod to the flock of turkeys once raised by one of the owners.

“We’ve started making t-shirts and patches and crests and ridiculous school stuff. But it’s fun to be playful like that with our house,” Grissom said.

AT A GLANCE

Schoolhouse Homestead

What: Stacie Grissom and her husband, Sean Wilson, both Johnson County natives, are restoring the former Union Joint Graded School No. 9 in southern Johnson County, to turn into a family home.

How to follow along: The couple has been documenting their project on Instagram @schoolhousehomestead and a blog, SchoolhouseHomestead.com.