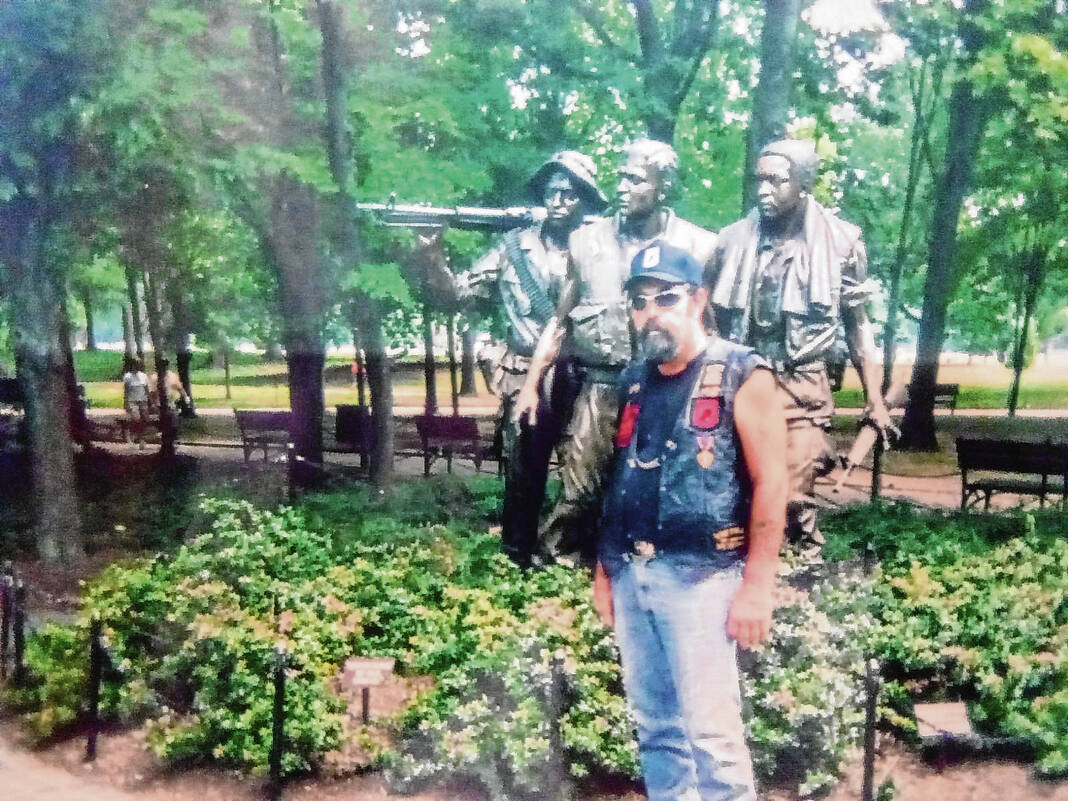

The tattoos, long hair and beard and Vietnam veteran leather motorcycle vest could be imposing.

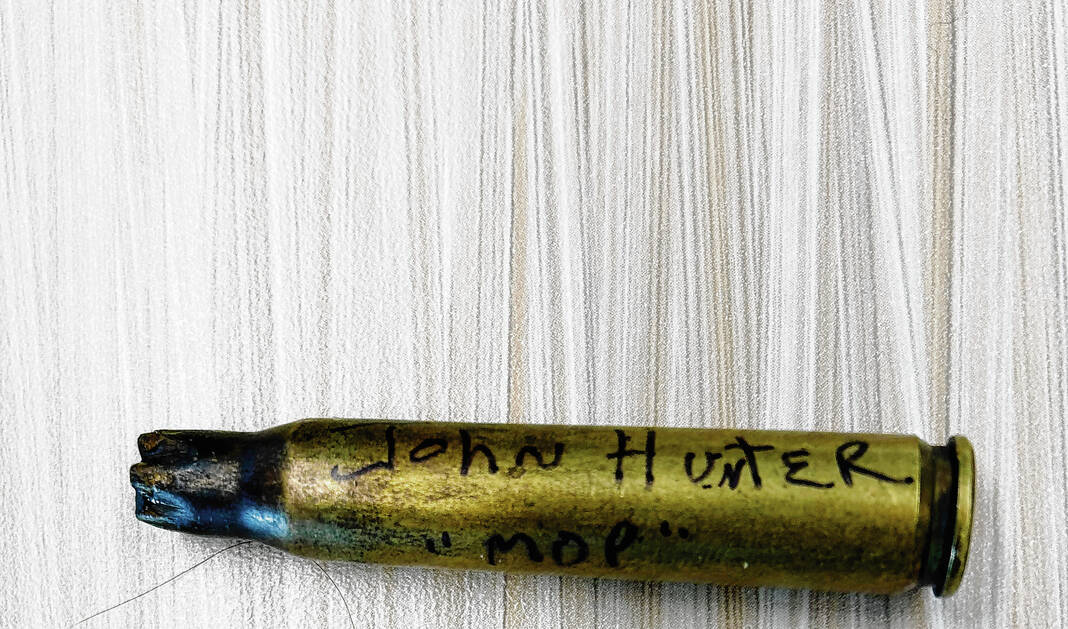

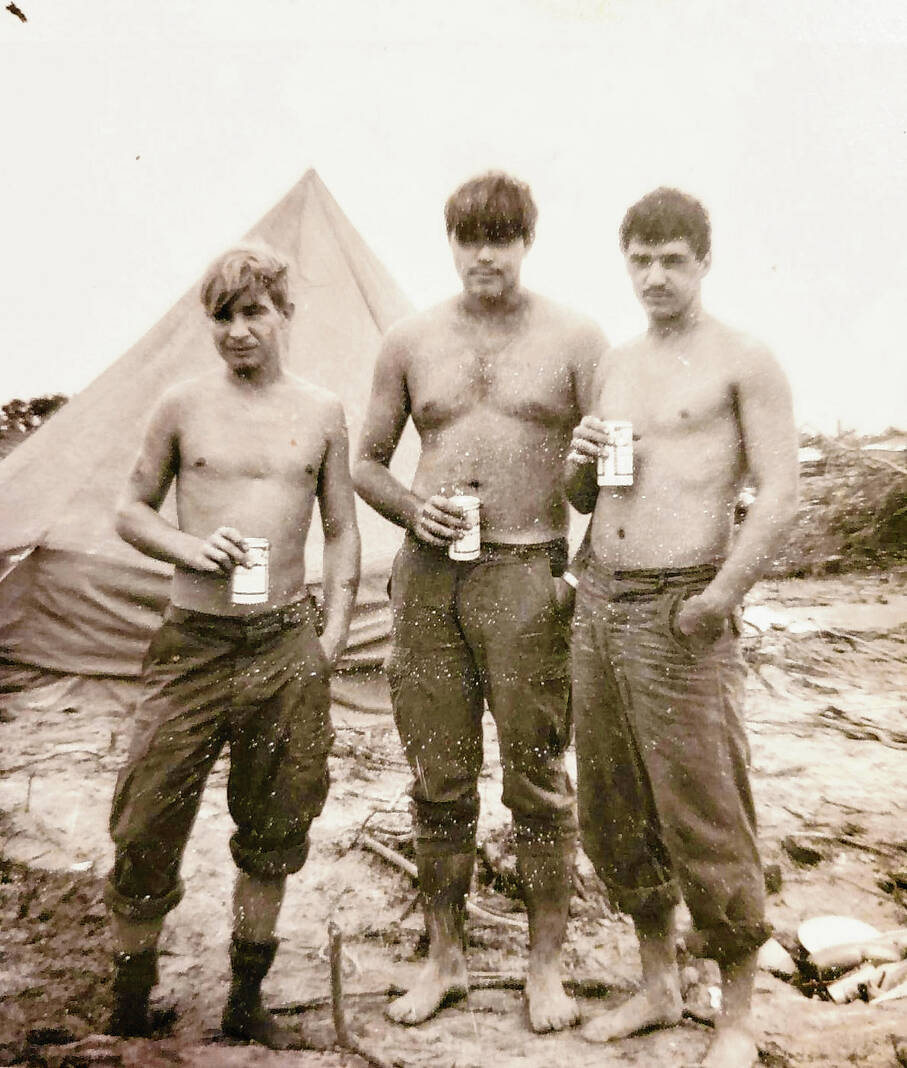

But for those closest to John Hunter, he was nothing but kind. He loved to work on cars, ride his motorcycle and be with his friends, both here in central Indiana and in Florida, where he and his wife Janet lived for part of the year. His constant companion was his dog, Muzzie; the two even looked the same, with grayish black hair and beard.

Hunter never met a stranger, said his daughter, Joy Reisinger. When he died in 2022, more than 1,000 people came out to his Needham home for a memorial service.

“The man had more friends than you can imagine,” Reisinger said. “It was a huge event. Friends from all over came to it. They ended up having an old car show in the back field.”

This summer, Hunter will be one of 500 Vietnam veterans to have their names added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund’s In Memory program. The goal is to honor and remember veterans who have suffered due to Agent Orange exposure, post-traumatic stress disorder and other illnesses as a result of their service.

For Hunter’s family, the inclusion is a chance to spotlight the sacrifices Vietnam veterans have made, and continue to make.

“It’s an honor to me, to be able to get him the recognition for not only what he did, and what he risked his life for, out there, but ultimately what took his life,” Reisinger said. “Vietnam, in a way, didn’t kill him then, but it did all these years later.”

The In Memory program was created in 1993, as the challenges Vietnam veterans faced in the decades after their service began to come into focus.

While the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. pays tribute to those soldiers who died in the war, it was important to recognize the many other victims.

“For many Vietnam veterans, coming home from Vietnam was just the beginning of a whole new fight. Many never fully recovered, either physically or emotionally, from their experiences. As these veterans pass, it is our duty and solemn promise to welcome them home to the place that our nation has set aside to remember our Vietnam veterans,” said Jim Knotts, president and CEO of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund.

Since it was established, more than 6,000 veterans have been honored through the program. A plaque was dedicated in their memory at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial site in 2004. The placard reads, “In Memory of the men and women who served in the Vietnam War and later died as a result of their service. We honor and remember their sacrifice.”

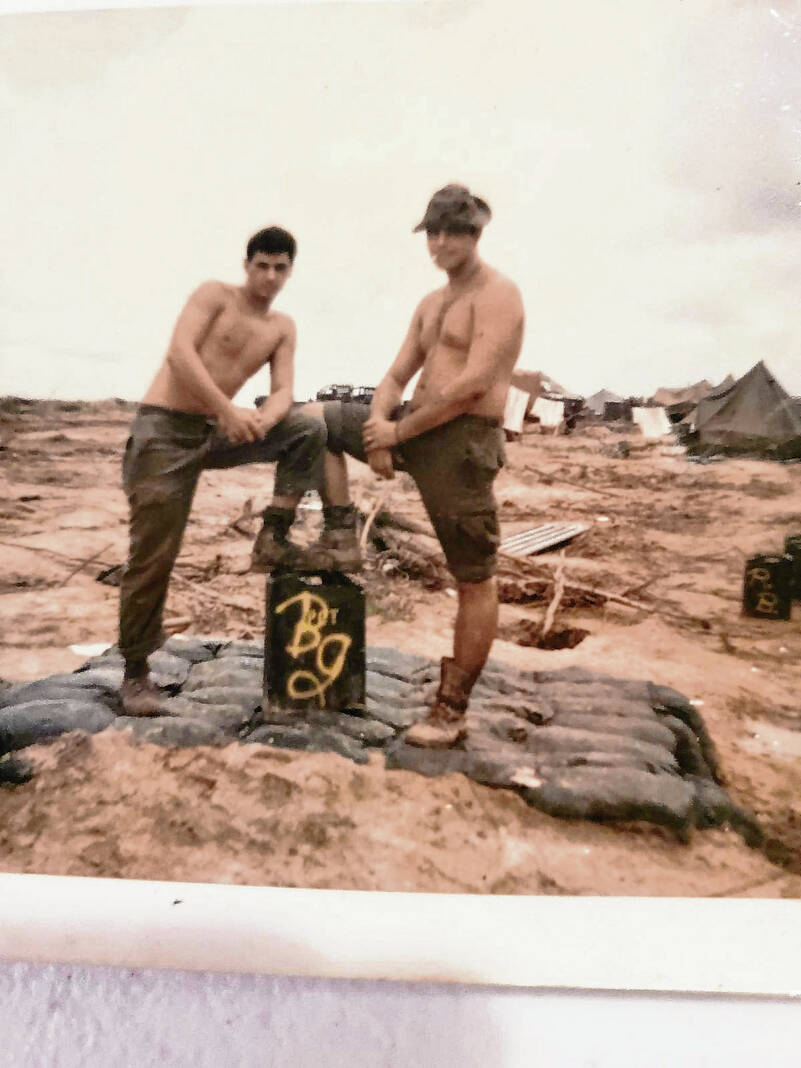

Hunter grew up in Whiteland before enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1966. During the Vietnam War, he served as part of the 27th Land Clearing Task Force — known as the “Jungle Eaters.” The task force was in charge of using modified dozers to clear the jungle so troops could move through.

One of Hunter’s close friends and fellow veteran, David Ellis, said they would go out for 30 days at a time to tear down vegetation and trees. Hunter served as lead plow, which meant he was “first in, first hit,” Ellis said.

Not only were they often the first to encounter enemy North Vietnamese troops, but they were constantly exposed to Agent Orange — the chemical herbicide used by the military during the war which was later found to cause significant health problems.

“I remember my dad saying this: Agent Orange would spray down on him like a shower. It was that strong,” Reisinger said.

Hunter completed his service in 1969, after receiving two Purple Hearts and a Bronze Star, among other medals. After his stint in the military ended, he married Janet, and they had two children, Reisinger and her brother, Paul Hunter. He made a career as a heavy equipment mechanic at Gradex before retiring in 2010, and had his own body shop on antique cars as a side job.

Hunter lived to be 73, but no one knew the havoc serving in Vietnam had on his body, Reisinger said. He was diagnosed in 2011 with myelodysplastic syndromes, which is where the blood-forming cells inside the bone marrow are poorly formed or don’t work properly.

The disease eventually developed into a form of leukemia, Reisinger said.

“He lived with that for years. In 2019, that’s where he really started to get sick with it. My mom was taking him up to the (Veterans Affairs) hospital in Indianapolis weekly,” she said.

In the last year of his life, Hunter received chemotherapy for seven straight days at a time, and the treatment appeared to have an impact, Reisinger said. His health improved and he was more active, even getting out into the garage to work on his cars.

But by early 2022, his condition spiraled downward. On March 7, 2022, he died surrounded by his family.

Since his death, Reisinger has worked to spotlight her father’s service, and the struggle that Vietnam veterans just like him are going through on a constant basis. She created a Facebook group where his friends and family can share stories and photographs.

Signing him up for the In Memory program was part of that. Reisinger had to apply for it, outlining Hunter’s service and time in Vietnam. After being accepted into the program, she was able to set up a virtual page at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund website.

Hunter will also be included in the organization’s The Wall That Heals display — a traveling replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial that includes honors for the In Memory participants.

“I’ve tried to do as many things as possible to keep his memory alive,” Reisinger said.

AT A GLANCE

In Memory program

What: A program allowing the families and friends of those who came home from the Vietnam War and later died the opportunity to have them be forever memorialized.

Who: Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, a nonprofit organization authorized by Congress in 1980 to build a national memorial dedicated to all who served with the U.S. armed forces in the Vietnam War.

How to honor someone: To apply online or download an application, go to vvmf.org/In-Memory-Program. To have a veteran considered for the 2024 In Memory national ceremony, you must submit your application to Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund by March 29, 2024.