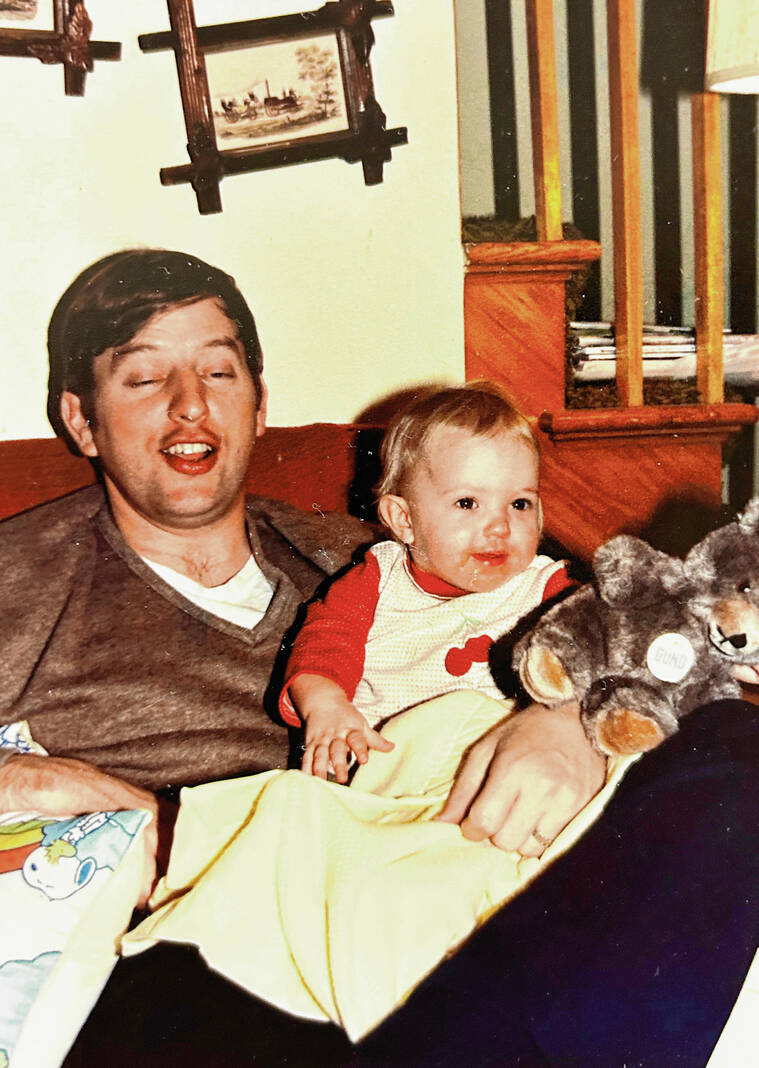

Becky Chapman, a speech pathologist at Roudebush VA Medical Center in Indianapolis, stands in front of a model of an A-10 fighter jet in her office on May 24. Chapman’s father, Capt. David E. Black, was killed in a crash at Camp Atterbury while flying an A-10 in 1983. She was drawn into health care for veterans because of her father’s service.

RYAN TRARES | DAILY JOURNAL

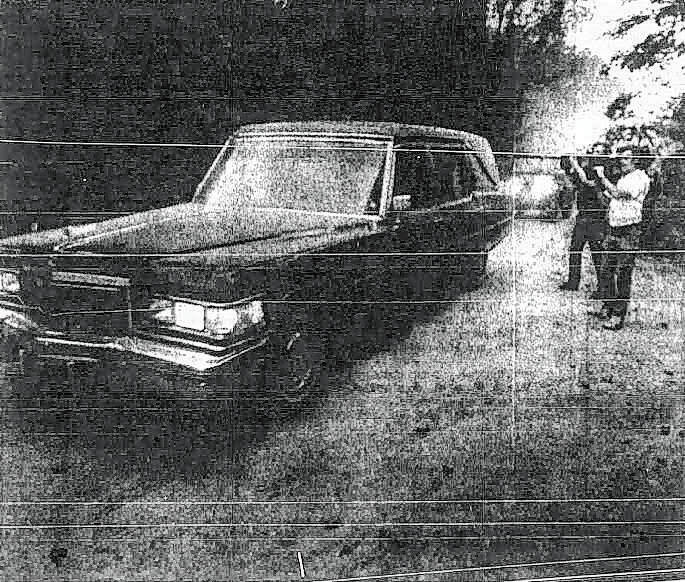

The booming crash and black smoke rising above the treeline signaled for miles around southern Johnson County that something had gone tragically wrong.

On the afternoon of July 12, 1983, an A-10 Thunderbolt II jet had crashed in a heavily wooded area of Camp Atterbury. The pilot, Capt. David E. Black, was killed when the plane went down and disintegrated upon impact.

Black left behind a wife and five children. One of his children, Becky Chapman, was too young to remember the grief and heartache that surrounded his death.

But his service — and his sacrifice — helped shape who she is today.

“My perspective on life is different than others. A fundamental belief of mine is everything happens the way it happens. And even if it’s hard, I wouldn’t be here if not for that,” she said.

Chapman has dedicated her life to serving veterans, working for the past 16 years as a speech pathologist at Roudebush Veterans’ Administration Medical Center. Every day, she helps men and women who have served their country regain the ability to speak, heal from brain injuries, recover from treatment for head and neck cancers, as well as a number of other conditions.

The chance to do so is made more rewarding when considering her father’s own military career.

“In the medical field, you can have really hard days where you start to question if you’re making a difference. In a way, it’s easier for me, because on days like that, I look at that veteran and think, it could be my dad,” she said. “It challenges me to always practice at the top of my game, because they deserve that.”

Inside the hospital room, Chapman stood over one of her patients, asking about how he was feeling and chatting with him about his morning.

George DeLay, a U.S. Army veteran, was admitted to Roudebush Medical Center after he was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a degenerative disease that weakens the nerve cells in the spinal cord and brain.

“We found out that the VA here in Indy took care of vets with ALS,” he said.

DeLay, a Columbus resident, had served in the Vietnam War in 1968 and 1969 with the 4th Infantry Division. When he arrived at Roudebush and was paired with Chapman, they immediately developed a rapport.

His condition had robbed him of the ability to speak and communicate, so Chapman worked with him on communication, particularly talking around his ventilator.

One day, DeLay had to take a swallow test to map his throat movements. Part of the test involved ingesting barium, which helps areas of the body show up on X-ray. Sometimes, swallowing it can be a challenge, so Chapman made a pact with him: if he passed the test, she’d give him a reward.

“Her reward was a Blizzard,” DeLay said, referring to one of his favorite ice cream treats.

Interactions such as this are what Chapman lives for. She attributes her passion for her job to her father, even if she doesn’t remember him.

Black was an 11-year veteran of the Air Force Reserve who frequently flew training missions over Camp Atterbury. On July 12, 1983, he had just completed his last target run of a 20-minute training mission. He was making a 180-degree turn, getting ready to return to Grissom Air Force Base near Peru, when he crashed.

Black and his family were living in the Chicago area at the time, but in an incredible coincidence, his two oldest daughters were attending summer camp just a few miles away from Camp Atterbury at the time of the crash.

“They were at the camp, heard about the crash, and my sisters say, as soon as they heard what had happened, they knew it was my dad,” Chapman said. “They were whisked away, guarded by everything, guarded by the news, until my mom could get there.”

With survivor benefits provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the family moved from Illinois to the southside of Indianapolis, where Chapman would grow up. She didn’t really understand what had happened to her father until she was much older.

“There was never an a-ha moment, I just knew that I didn’t have a dad. But I didn’t understand the sacrifice my mom made, what that would mean, raising five of us and trying to balance everything,” she said.

Only when she was in high school did she realize how her father’s death shaped their lives afterward — not only in a tragic way, but also serving as the reason they live where they do.

High school proved to provide another important realization in her life. Chapman was thumbing through a career option booklet provided by her counselors one day when she discovered speech pathology.

“I didn’t know really what I wanted to do, and the book popped open to that,” she said. “I thought, maybe God is trying to tell me something. I read about it, it looked good, and I never looked back.”

Benefits from the VA allowed her to attend college at Butler University, and after graduating, go to graduate school at Indiana University.

During her time at IU, she was mentored by a woman who also worked for the VA. The relationship led to her placement at Roudebush Medical Center in 2003, where she fell in love with the work.

“Of course, there was my dad and wanting to give back to the VA. But also, working here as a student, the way we interact with patients, we’re like family,” she said.

Chapman, who lives on the west side of Indianapolis now, has been a speech pathologist for 18 years, 16 of which have been at Roudebush.

“The VA has been weaving its way through my entire life,” she said.

In her office, Chapman keeps a wooden model of an A-10 jet, an aircraft designed to destroy tanks and armored vehicles. The model not only serves as a tribute to her father, but helps her connect with the veterans she treats.

“I tell them that’s the kind of plane my dad flew,” she said. “They want to know more, and I tell them about the crash. A lot of them remember it. It’s an additional level of connection.

“They say I’m the daughter of a ‘tank killer.’”