With a freshly envisioned gallery, the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields hopes the new space leads to new ideas, new connections and a new way of looking at American art.

The museum has reopened the renovated galleries, featuring a reimagined ordering of its American art collection. Curators have used thought-provoking pairings to emphasize ideas rather than a chronological order of art.

As a result, visitors to the new galleries will find popular works by Georgia O’Keeffe, Norman Rockwell, John Wesley Hardrick and William Merritt Chase alongside recently acquired works of art by Charles Henry Alston and Mexican-born artist Ana Teresa Fernández.

Museum curators wanted to reframe what “American art” means, making space for artists and ideas that have traditionally been left out of the genre.

“American art begins with this country, so it’s a conversation about what this country is, who is an American, what landscapes or places represent America,” said Michael Vetter, associate curator of contemporary art and interim curator of American art. “It’s a conversation that goes back to the colonial period, but still is still relevant to our own time as well.”

Longtime fans of the museum will recognize some of the most familiar pieces: “Jimson Weed” by Georgia O’Keeffe, “Hotel Lobby” by Edward Hopper, and Angel of the Resurrection, the wall-sized Tiffany stained-glass window that has been situated in the museum for years.

But alongside of those are exciting and pieces that tie into common themes. For example, the museum has displayed a projection piece by Kara Walker taking up an entire wall. “They Waz Nice White Folks While They Lasted (Sez One Gal to Another)” features characters cut from black paper perform mysterious actions before the projected backdrop of a great steamboat.

The piece is unusual because it not only departs from Walker’s traditional approach, but also is centered around the Civil War era.

“The Civil War has a weird influence on American art, because there are not big paintings of battles nor paintings of enslaved people and the horrors of that. It just wasn’t a popular subject for paintings,” Vetter said. “(Walker’s) work is always so focused on those darker and horrific moments in history.”

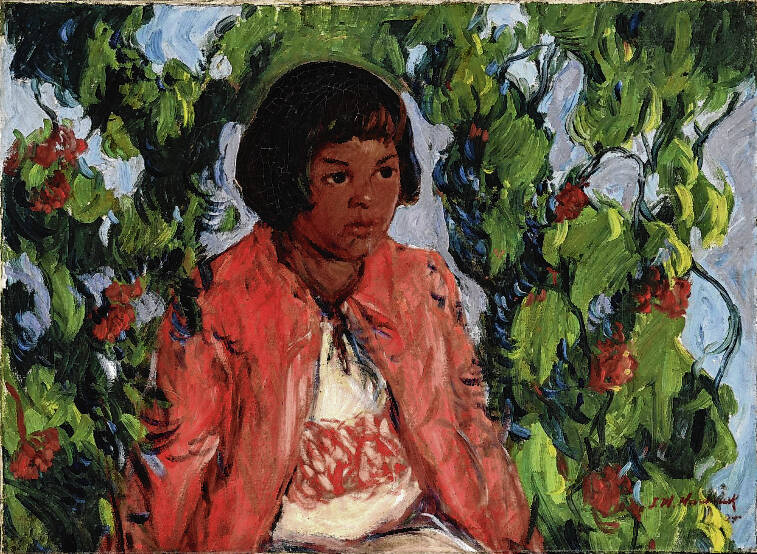

In another area, John Wesley Hardrick’s famed “Little Brown Girl” hangs next to a new piece by Indianapolis artist Kyng Rhoades — “Big White System,” which addresses Indiana’s racist history and the role the Ku Klux Klan played in the state.

“There was a real intentionality in the way we put paintings together to create reflection points on each didactic,” said Tascha Horowitz, director of content and interpretive engagement. “The intention of the project is about debate, it’s about conversation, it’s about posing questions and not really answering them, hoping to spark thought.”

The museum’s permanent galleries, including those housing the American art collection, were created in 2005, and had remained relatively static ever since. As leadership within the Indianapolis Museum of Art thought about ways to refresh and enliven the space, they also pondered how to update people’s connection to the artwork itself.

“In recent years, we’ve really been turning out attention to focus more on the permanent collection galleries and to give them the updates they so desperately need,” Horowitz said.

With funding from the Luz Foundation, Newfields was able to transform the galleries while also reconsidering how the artwork is presented. The project allowed museum staff to think about goals such as more inclusive storytelling, bringing artworks from across the collection together to explore themes, and making space for community voices, Horowitz said.

“We have updated goals and guiding principles for the way we approach out gallery projects, and we wanted these galleries to be more in line with those goals,” she said.

A key part of the reimagining of the gallery spaces was include voices of people with different lived experiences. Newfields staff reached out to a select group of Indianapolis-area artists and creatives, including Rhodes, Nasreen Khan, Tatjana Rebelle, Jordan Ryan and Bobby Young, who now call themselves The Looking Glass Alliance.

The group was invited to create content around the artworks on display. Those contributions include poems, paintings, Indianapolis-focused stories and a digital interactive that highlights the lives of African American artists.

“We really leaned into the artist aspect of it, and people working outside the traditional fine arts. We have a couple people who are painters, but also people who approach their work through literature, history, social activism, a variety of fields,” said Maggie Ordon, interpretive planner for the museum.

Interactive displays are pepper throughout the galleries to help illustrate some of the questions the artists of particular works were asking.

“We really wanted to make the gallery seem more lively and active, to give guests an opportunity to participate and express themselves,” Horowitz said.

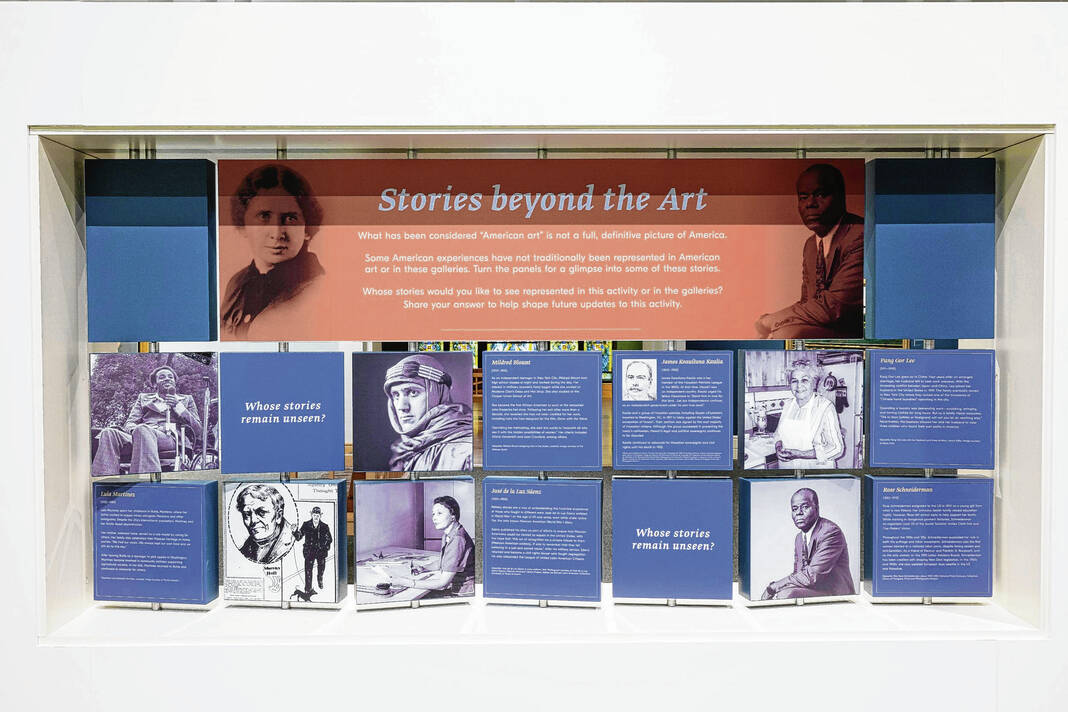

One of the more unique features is called Stories Beyond the Art. The display tells short snippets of people from a variety of different backgrounds, and the experiences they’ve had. People can learn more about these individuals, and suggest the types of accounts and experiences they’d prefer to see in the future.

“This idea, to just have stories about Americans who might not be depicted in art on the walls has really resonated with people,” Ordon said. “The goal is to eventually have artwork in the permanent collection that gets at these stories. Until then, this is a reminder that historic American art doesn’t tell a complete picture of American history.”

While the galleries will house works from Newfields’ permanent collection, that is not to say the displays that have been created are now stuck in place, Ordon said.

“It’s not like it’s a permanent thing. It’s meant to change. We’ll be doing updates, and this is just one step to reimagining how we display and interpret American art,” she said.