An expansion of weather monitoring equipment across Indiana could improve forecasting for meteorologists. But meteorologists need the public’s help to expand Indiana’s under-sized mesonet.

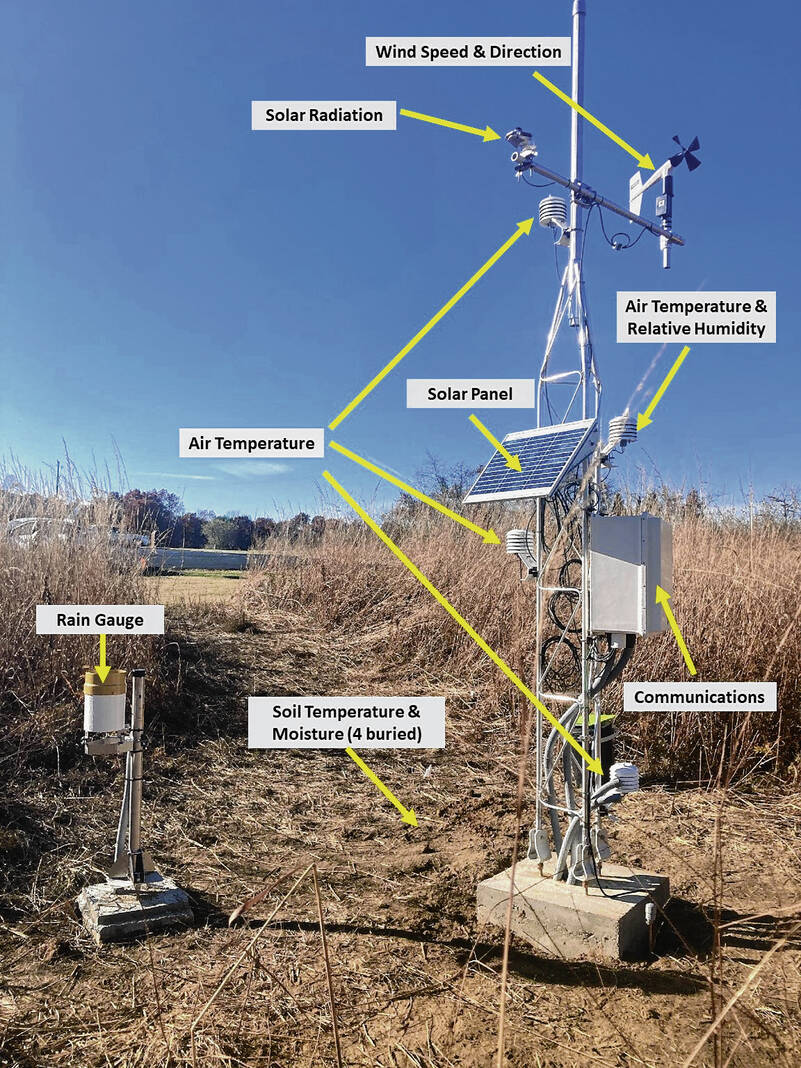

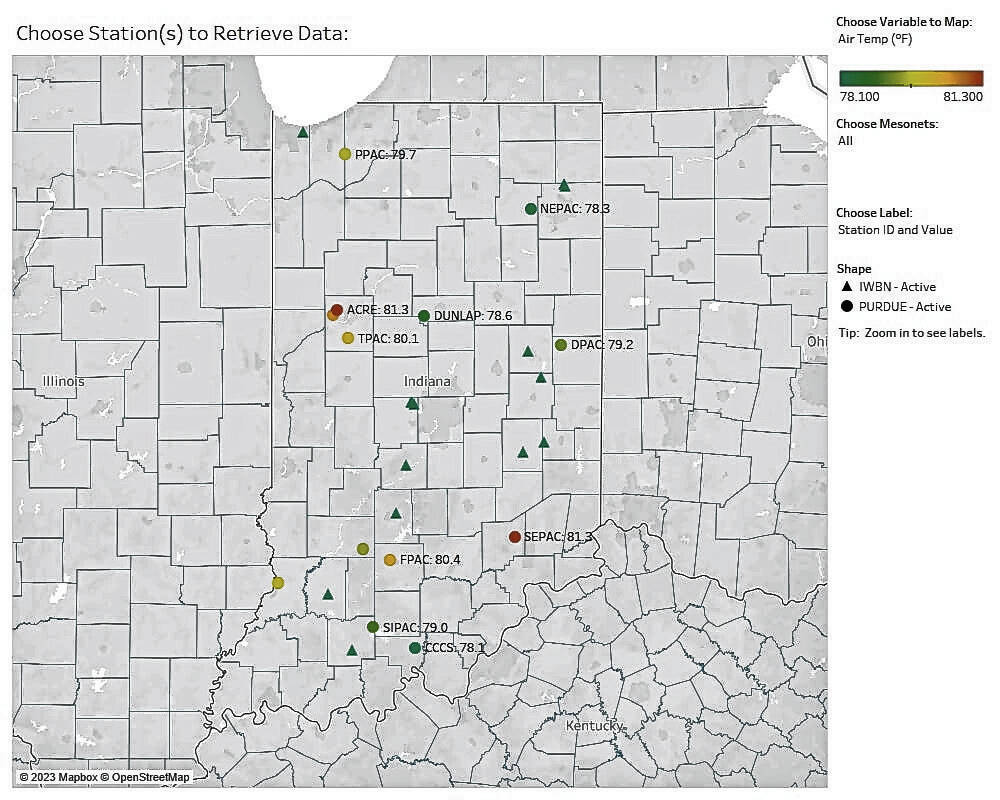

The mesonet is a network of several high-resolution weather monitoring stations with high-quality instruments that are being managed through a designated, skilled center. They collect a variety of data for forecasters in real-time, including air and soil temperatures, solar radiation, relative humidity, precipitation wind speed and wind direction.

Right now, the state only has about 30 or so stations. To improve forecasts, experts say the system needs to have at least one station in all 92 counties — including Johnson County.

The more stations that are operating and the more data that is collected, the better forecasts will be.

How the data is used

The data is sent to several sources and fed into a variety of programs. At the National Weather Service, mesonet data helps them monitor severe weather and determine the timing of storms and how strong they will be, said Sam Lashley, warnings coordination meteorologist for the Indianapolis Forecast Office.

The wind sensors on a mesonet, for example, help meteorologists monitor low-level wind shear — the difference in wind speed and/or direction over a relatively short distance in the atmosphere — and how it can affect tornado development, Lashley said.

NWS does use data from their own monitoring stations, but they are spread out far and few between, Lashley said.

NWS is currently relying on a lot of home weather equipment in Indiana for some of their data, but that equipment isn’t always maintained or quality-controlled, Lashley said. The mesonet is a professional standard that will be quality controlled, maintained and routinely serviced, he said.

“It will meet the standards for research and operational use,” Lashley said.

The weather service has also seen in other states how mesonet networks have taken off and improved weather forecasting and severe weather warning decisions by the agency, he said.

Networks vary by state

Many states already have at least one mesonet network in place, though they vary in size

Ohio, Illinois, New Mexico, Florida, New York, Kentucky and Oklahoma all either have or are close to having a mesonet station in each county within their state.

Oklahoma, located in the heart of the Tornado Alley, is one of the more well-known mesonet networks in the United States. The Oklahoma Mesonet is made up of 120 stations, with at least one station in each of the state’s 77 counties, according to Oklahoma Mesonet.

“Oklahoma is sort of the gold standard that everyone strives to become like,” Lashley said.

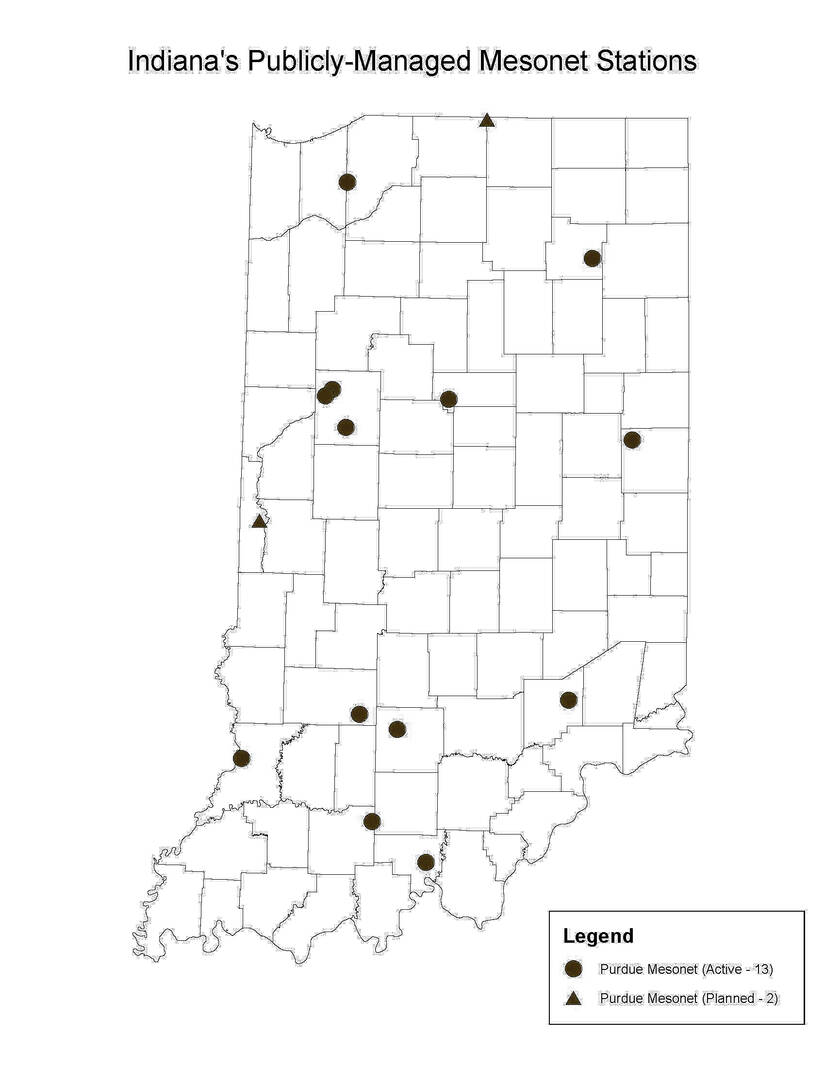

Indiana has two mesonet networks that work together to ensure that high-quality weather data is provided to the NWS and other stakeholders: the Purdue Mesonet, operated by the Indiana State Climate Office at Purdue University, and the Indiana Water Balance Network, or IWBN, operated by the Indiana Geological & Water Survey.

Both networks are part of the weather service’s National Mesonet Program, which provides partial program support to enhance their forecast data needs.

A wanted expansion

The Purdue Mesonet, operational since 1999 and providing data since 2002, is made up of 13 stations across the state. The IWBN operates another 15 stations.

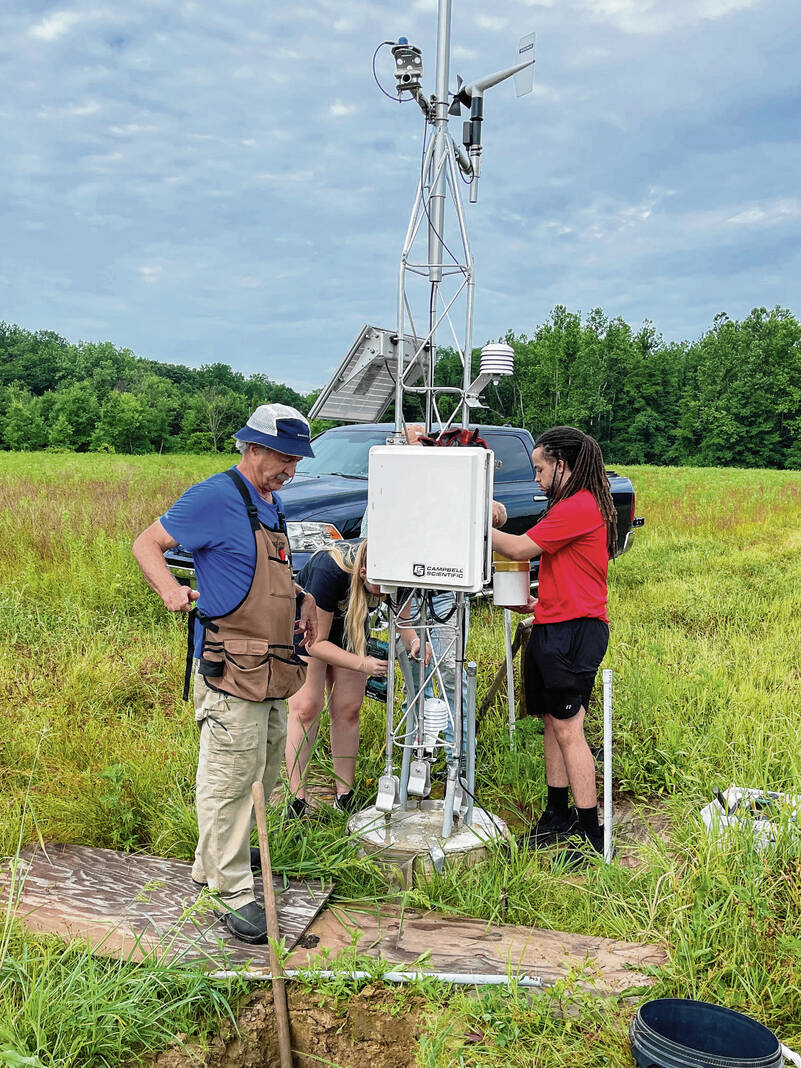

Originally, Purdue Mesonet stations were all located at Purdue Agricultural Centers. When Indiana State Climatologist Beth Hall started at the State Climate Office in 2019, she pushed for an expansion of Purdue’s network. Since then, the network has grown from nine stations to 13 —with two more on the horizon, she said.

Hall’s goal is to have a station in all 92 Indiana counties, which would go a long way to improving forecasting. It could improve meteorologist ability to pick up on storm paths and climate patterns, she said.

“In an ideal world, we’d have a weather station every step we take,” Hall said. “But to be realistic, to have one in every county would get us there.”

This goal has a major challenge: funding. It’s cheap to install an approximately $12,000 station that will need repairs or parts replaced as time goes on, she said.

Other investments go beyond the physical station itself that increase costs: personnel to maintain and repair the stations, websites for people to find the data and setting up programs to feed the data to wherever it needs to go, Hall said.

Mesonets can be funded both publicly and privately, and some people and organizations have even received Federal grants to fund them. These grants are extremely competitive, and are often time-limited, she said.

In Kentucky, their system is partially funded in the state budget — after more than a decade of effort to have it included. Even then, their system gets funding from a variety of other sources, Hall said.

Ohio’s system received a $250,000 donation from Ohio State University alumni that was used to revitalize and expand the network. This was on top of other funding sources, she said.

Many benefits

An expanded mesonet network is a “win-win” for many people, Hall said.

“Having a good dense network in a state can benefit the National Weather Service,” Hall said. “It can benefit contractors, construction, infrastructure, it can benefit tourism. It can benefit the state agencies, like Homeland Security, natural resources and the park system.”

As an example, Hall said the weather service office in Louisville would have more information for the forecasts and warnings they issue in Indiana. The Louisville office primarily covers central Kentucky but also covers part of southern Indiana.

The forecast office has access to a robust mesonet system and its data for forecasts in Kentucky, but not so much for Indiana, she said.

“Imagine all of the other weather service offices and counties across Indiana that because we don’t have a well-covered, well-funded expanded mesonet, the residents of Indiana are losing out,” she said.

Farmers are another group that will benefit. Air temperature, soil temperature and soil moisture are key pieces of information for farmers to know for planting, harvesting and irrigation, Lashley said.

All of these data points can be measured by mesonets.

“Having that detailed information, it’s definitely saved farmers thousands of dollars, so they don’t have to needlessly water,” Lashley said.

Mesonet stations can also measure air quality, providing more detailed information about conditions so those who are more sensitive to air quality issues can be more prepared, Lashley said.

“Pretty much if you think of weather and being impacted by it, this mesonet will certainly improve that information,” he said.

Outlining a plan

In July, the first-ever Indiana Mesonet Meeting took place in Plainfield. Sixty people from a variety of fields including academia, agriculture, environment, government, public safety and more came together to discuss the monitoring stations and their limitations.

Officials introduced also stakeholders to the concept of a mesonet station, its benefits and the current funding situation. They also identified the need for an Indiana Mesonet Advisory Board, which would help pave the way forward for Indiana’s network.

Both Hall and Lashley attended the meeting, which they said exceeded their expectations. Since the meeting, both Hall and Lashley have been contacted by groups asking for more information, wanting to set up meetings to discuss mesonet more or news interviews, they said.

“It’s been fantastic,” Lashley said.

Having an advisory board would help with convincing people to invest long-term in the network. Kentucky has an advisory board made up of stakeholders like the Kentucky Farm Bureau and a rural water association and people who appreciate the value of mesonets, Hall said.

If Indiana had something similar, stakeholders could explain what mesonet is and help advocate for an expanded network, she said.

What’s next?

For right now, Hall and Lashley are working to spread the word about mesonet and see who may be interested in helping with the expansion. Funding is one of the major issues, along with sustaining the network for the future.

For Indiana, Hall is considering pursuing Private and philanthropic angles for donations. Other possible funding opportunities could come through agricultural associations or even the state budget. The possibilities are endless, she said.

Officials do not necessarily want someone to incur the ongoing costs or pay for the station. Sometimes just having someone say they’re willing to give officials some land for the station is enough, Hall said.

“That could be one of the easiest and cheapest ways for people to get involved is to reach out to us,” she said.

People volunteering their time is another way to help the efforts, like someone who may volunteer for the future advisory board, Hall said.

Hall encourages those wanting to learn more about Purdue Mesonet and how to get involved to go to their website, ag.purdue.edu/indiana-state-climate/purdue-mesonet. On the site, people can also find contact information for the State Climate office, she said.