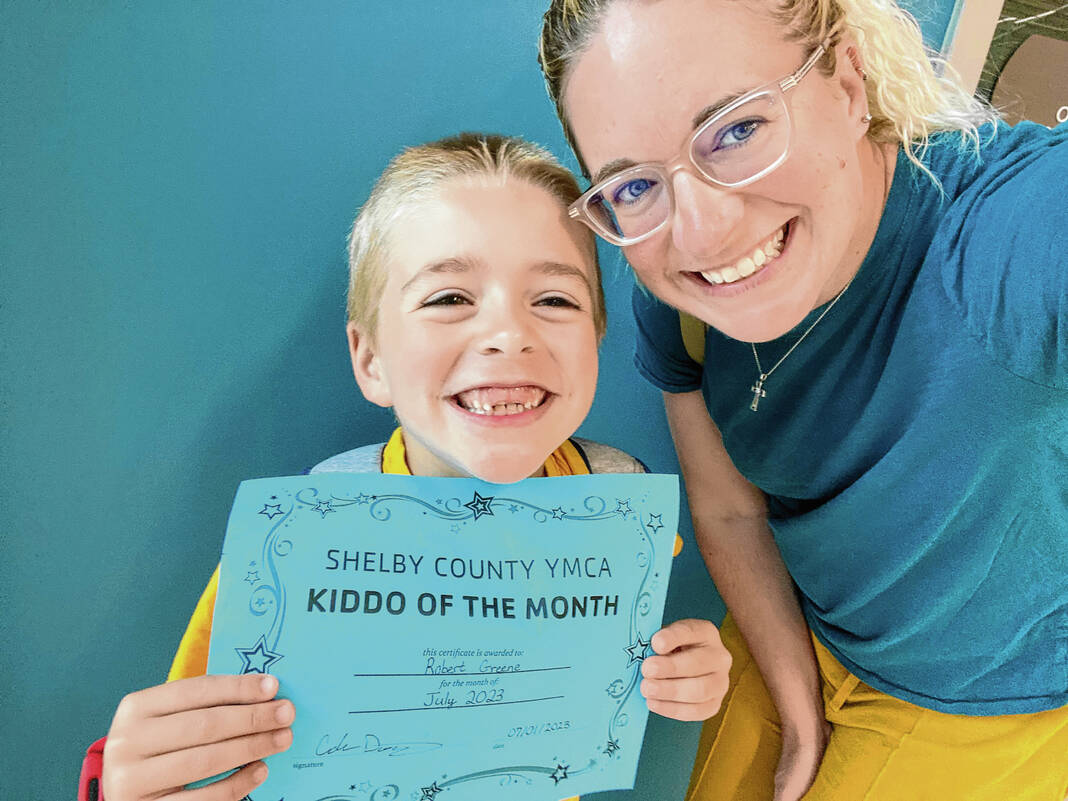

State Rep. Robb Greene, R-Shelbyville, poses for a photo with his son RG, bottom, earlier this year at the Indiana Statehouse. Submitted photo

Local lawmakers are urging Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb to reconsider proposed rate cuts for a specialized form of treatment for autistic children.

State Rep. Robb Greene, R-Shelbyville, authored a letter to Holcomb on Aug. 29 sharing the impact Applied Behavioral Analysis, or ABA, therapy on had his son RG, who has Autism Spectrum Disorder, urging Holcomb to reconsider the cuts and invite stakeholders in for a collaborative discussion on the new rates. Greene, who is in his first term, represents portions of Johnson and Shelby counties.

A bipartisan group of lawmakers from both chambers signed Greene’s letter, including local Reps. Michelle Davis, R-Whiteland, and Craig Haggard, R-Mooresville, and Sen. Greg Walker, R-Columbus. A total of 13 senators and 29 representatives from across the state signed on to the letter.

The proposed changes

Officials in Indiana’s Office of Medicaid Policy and Planning, a division of the Family and Social Services Administration, have proposed establishing a rate standard for ABA treatment that would go into effect in late 2023 or early 2024. FSSA pays for coverage of ABA therapy, which can improve social, cognitive and behavioral outcomes in some children with Autism Spectrum Disorder as well as the overall well-being of the child and their family, according to FSSA.

Medicaid first began covering these services in 2016. Because there was not “meaningful data” on which to set base rates at that time, FSSA has been paying providers a percentage of the amount they chose to bill the state rather than a statewide rate for ABA therapy services, according to the agency.

For the majority of ABA services, the percentage is currently 40%, causing payments to vary widely from provider to provider. Payments currently average $91 for hourly rates but range from $46 to $222 hourly for the same services, according to an Aug. 8 presentation by the Office of Medicaid Policy and Planning.

FSSA officials say ABA expenditures have increased by more than 50% per year over the last three years. For 2022, ABA claims payments represented a Medicaid expense of $420 million for 6,200 children and young adults.

These costs, which are described as unsustainable, will continue to grow if an ABA fee schedule is not implemented, officials say. Indiana’s reimbursement amounts are also significantly higher than other states providing similar services.

Last year, state officials began to work toward establishing a uniform rate, reaching out to ABA providers and learning how other states reimburse the services. The goal is to transition to “transparent statewide ABA rates that promote uniform access for families and allow providers to retain a stable workforce, while ensuring sustainability for Indiana’s Medicaid program,” according to FSSA.

Under the proposed changes, the new preliminary rates would be $55.16 per hour of ABA therapy administered by a registered behavioral technician, which is the majority of ABA services, or $103.77 for services rendered by a physician or other qualified health care professional.

Personal for lawmakers

In his Aug. 29 letter to Holcomb, Greene says the proposed rate cuts would have a “disastrous impact” on the access to ABA therapy treatments. The issue is deeply personal to Greene as ABA therapy saved his son’s life, he said.

“I saw the proof in what ABA did for our family, for our son, and it just compelled me to speak up and act,” Greene told the Daily Journal Wednesday.

When Greene’s 7-year-old son RG was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder at age 3, he was functionally non-verbal. As Greene and his wife began looking at intervention and treatment options, they came across ABA therapy. Greene was initially skeptical.

But after three to four weeks of treatment at the Bierman Autism Center in Broad Ripple, RG’s communication began to improve. He began to advocate for himself and found ways to cope with tantrums and outbursts, Greene said.

“I immediately just became a true believer in it,” he said. “ABA, I tell people it saved my son’s life … because when you look at the path your child would be on without intervention, and the path that he took through having this intervention and where he’s at now, it would be night and day.”

Within the first year of ABA therapy, RG acquired many life skills, including beginning and mastering potty training and efforts made toward dressing himself. He also began to play more appropriately with toys, and made great strides in speech, Greene said.

After three years, RG graduated from therapy and started kindergarten at a public school. Without ABA therapy, this would not have been possible, Greene said.

One of the reasons why Greene ran for office last year was to advocate for special needs and workforce development. While there were people who cared about the issue at the Statehouse, he didn’t see legislators who understood it on a personal level like he did, he said.

Since then Greene and several other lawmakers who understand the issues on a personal level have been elected to the Statehouse, he said. This includes State Rep. Craig Haggard, R-Mooresville, whose youngest stepson is on the spectrum.

Haggard’s stepson struggled in school and went through ABA therapy. Now his stepson, who is 20, is in his second year of studying physics in college.

“I attribute a lot of that to going through those different therapies, and helping us discover what he needed to grow with having autism,” said Haggard, who represents portions of northwestern White River Township in Johnson County, along with areas of Morgan and Hendricks counties.

Haggard co-signed Greene’s letter, and believes it’s worth the time to take a step back and make sure the rate is at the right level. This is so the state doesn’t lose providers and kids don’t lose access to an effective therapy, he said.

“These things are always tough. … I just think that something so important, things like this are always worth taking the extra time to make sure we do it right or the best we can,” he said.

Hope for compromise

Greene and some other lawmakers were able to sit down with staff from the FSSA, Holcomb’s office and the Indiana Medicaid Director about the changes last month. During the conversations, they were able to tell their side of the situation and experiences with the therapy, he said.

Greene believes this is only the start of the conversations needed before a final rate proposal is made. It’s not just lawmakers who are speaking up, a grassroots movement with parents getting involved across the state sparked, he said.

“They’re engaged, they understand what’s at stake,” Greene said. “So we’re trying to have that conversation and find a compromise here on this rate that works for providers and the state and for parents so that nobody loses access.”

Advocates and allies of children with autism have been vocal about their opposition to the proposed rates — including Indiana ACT for Families. The organization is a broad coalition of Hoosier families, ABA therapists, ABA therapy providers and stakeholders working to advocate in support of promoting access to high-quality ABA therapy services in Indiana.

In August, Indiana ACT for Families sent a letter to Holcomb on behalf of families urging him to step in. In the letter, families said they feared the proposed rates would force ABA centers to close across the state, causing their children to “lose access to the care they need.” They also helped organize a rally outside the Governor’s Residence in Indianapolis.

For Greene, an ideal compromise would be a rate that a majority of good providers can live with. Haggard believes a compromise is possible if officials can find a way where the rate still helps patients while not hurting businesses who provide the services, he said.

Providers can give feedback

Last month, Holcomb said it was a “long overdue” process to establish a rate. He also said it would be unfair to everyone involved to slow down an ongoing process that has been months in the making, the Indiana Capital Chronicle reported.

Holcomb also said officials will make sure to “get it right” and arrive at a fair place for families and the state, the news outlet reported.

Setting an ABA rate that’s reflective “of the true cost of care plus a reasonable overhead” will ensure that all children on Medicaid who need services will continue to have sustainable access, said Michele Holtkamp, director of FSSA’s Office of Strategic Communications and Public Affairs.

“ABA is a Medicaid-covered service today. That will not change when the new rate is adopted,” Holtkamp said.

Federal requirements require the agency to operate a program and set rates reflective of the efficiency, economy and quality of care. The agency has a responsibility to both Hoosiers receiving Medicaid and taxpayers to make sure the program remains sustainable, she said.

The approach used to determine the preliminary ABA rates is the same one the agency uses when determining rates across the state’s Medicaid services. It is based on data collected from providers on the actual cost of providing the service, Holtkamp said.

This data is then used to set a preliminary rate that the agency shares with providers for further comment, Holtkamp said. FSSA plans to collect provider feedback before establishing the final rates.

The new rates will also be included in the Medicaid rate matrix, meaning they will be reviewed at least every four years. A yearly index will also provide adjustments annually when necessary, according to FSSA.