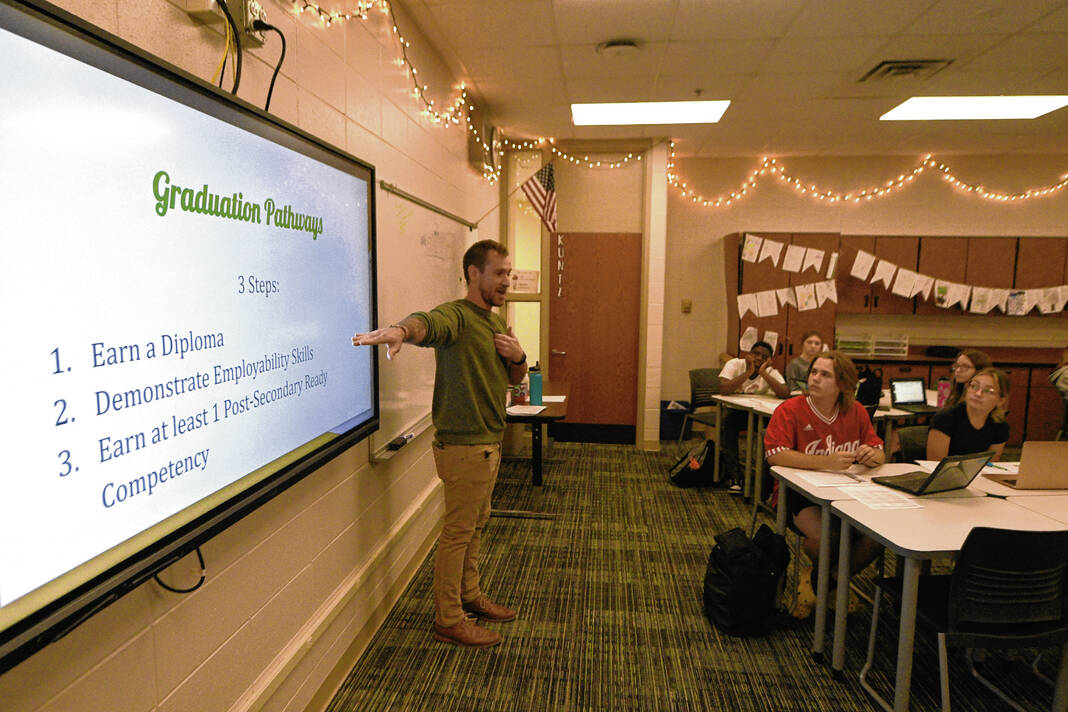

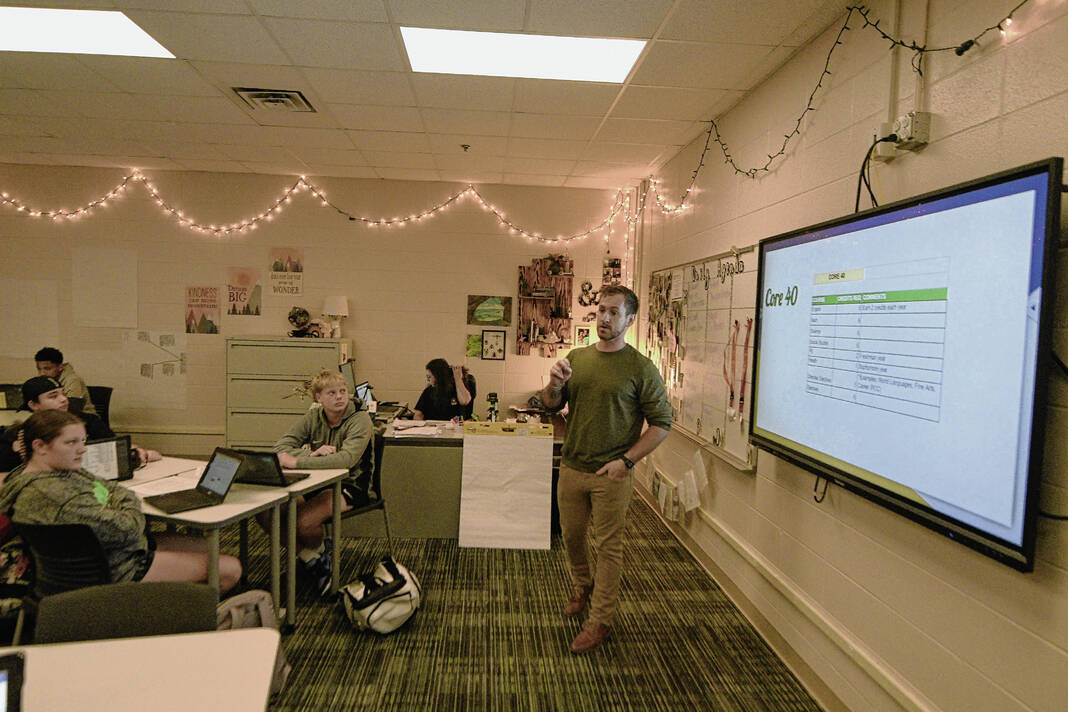

Greenwood counselor Ben Sutton talks to students in Laura Kuntz’s ninth-grade English class. Sutton is responsible for keeping track of 423 students as a counselor.

Andy Bell-Baltaci | Daily Journal

At Greenwood Community High School, there is no average day for a school counselor.

Ben Sutton, a counselor at the school, is responsible for making sure 423 students are on track to graduate. Beyond that, he has to assist students who are experiencing emergency situations regarding their mental health. Mental health crises, along with a heavy caseload, make being a counselor unpredictable and difficult to manage at times, Sutton said.

“Any time you have students talking about self-harm or suicide, everything else falls on the back burner and you have to deal with that situation. Anything you planned to do during that time gets postponed or forgotten about. That’s pretty much a constant battle: should I meet with students in one-on-one groups or classroom lessons? Whatever you choose, you neglect the other responsibilities or expectations.”

A statewide struggle

Sutton is not in a unique situation. Across Indiana, schools are struggling with a counselor shortage, as school administrators balance budgets and make tough decisions between hiring more teachers and hiring more counselors. During the 2021-22 school year, there were 694 students for every school counselor in Indiana, the highest ratio of any state in the nation, according to data from the American School Counselor Association. The association’s recommended ratio is 250:1.

While Johnson County school districts have more counselors than the state average, they are still well above the ASCA recommendation. Using data from the last official student count day in 2022, Indian Creek schools had the highest ratio of counselors to students at 690:1. Other districts fall below that by varying degrees: Greenwood, 656:1; Center Grove, 628:1; Clark-Pleasant, 456:1; Edinburgh, 403:1 and Franklin, 390:1.

Ruthie Leeth, counseling director for Center Grove Middle School North, is one of two counselors at the school. Center Grove’s two middle schools have an average of 588 students for every counselor, Leeth said.

“It’s hard. I don’t feel like I’m able to work with as many students as I would if I had a smaller caseload,” Leeth said. “Sometimes I feel like I’m just scratching the surface of what our students need and our families request.”

Shannon Sedgwick is the only counselor for the roughly 600 students at Clark-Pleasant’s Grassy Creek Elementary School. With that many students to account for, students who aren’t exhibiting the most severe needs often get overlooked, Sedgwick said.

“I have a caseload of students for weekly or biweekly meetings,” she said. “If someone is in an immediate crisis, how do I delegate the students I see every week? I can’t see you because another student is in an immediate crisis. While juggling that I’m making the choice to service one student over another based on needs. I’ve had to do that more than I’d like to admit.”

Mental health needs increase

While Sutton’s primary job is to make sure Greenwood students are on track to graduate high school, a rise in mental health issues since the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in more time being spent assisting students facing those challenges, he said.

“The emotional needs of students have skyrocketed since the pandemic. Once students are given the opportunity to talk, it opens a Pandora’s Box, and it snowballs into other areas,” Sutton said. “It seems like nowadays every student is struggling in some way emotionally. When they look for help they often turn to guidance counselors trying to find the answer. Sometimes they talk to their teachers about their problems but they have 30 other students, so it’s not uncommon for a teacher to direct them down to guidance.”

Data gathered at Center Grove has shown a decline in overall mental health from the 2021-22 to the 2022-23 school year, Leeth said.

“The academic concerns we addressed were almost double from ’22 to ’23 and the family and home concerns were up 30%. The behavior and peer-conflict meetings we had for students were over double from the previous year and mental health concerns were up 36% from the year before,” she said.

Finding solutions

While mental health and behavioral concerns are increasing, school administrators have been able to supplement counseling staff with other mental health professionals to try and ease the burden. At Center Grove schools, for example, 11 school social workers help address some of the more serious mental health crises, allowing counselors to focus on their primary tasks, such as class scheduling, letters of recommendation, graduation planning and college and career guidance, said Christy Berger, director of school counseling and mental health.

“Social workers deal with mental health and crisis response. Students with suicidal thoughts go through crisis response, making sure students have basic needs (met),” she said. “As a team we track how we support students. Our time is spent supporting students academically, with home concerns, mental health concerns, friendship concerns. We also track students with the Columbia-Suicide (Severity Rating Scale), a screener that identifies the risk of students who have suicidal thoughts.”

While the ratio of students to counselors at Indian Creek schools is greater than at other county school districts, the corporation’s three mental health counselors are able to assist students to decrease the workload.

Lindsey Crouch is the only counselor at Indian Creek Middle School. She normally would be responsible for all of the school’s 481 students, but with the help of one of the school district’s three mental health advisors taking a third of those students, Crouch works with a more manageable 320 students, she said.

“With extra people, I can be more intentional and it’s very helpful for me feeling that support,” Crouch said. “I feel I’ve grown as a counselor. I’m trying to do a more proactive approach. I will push into classrooms once a month per grade level. I’m doing more small groups, a positive coping skills group, a success skills group, I have a grief group every year so I can reach more students.”

Along with two full-time counselors, Edinburgh schools has a behavioral skills specialist for additional behavioral support. Administrators have also partnered with Adult & Child Health, which has provided a mental health specialist for each of the district’s three school buildings, Superintendent Ron Ross said.

Looking to legislators

In order to reverse the shortage of counselors, there needs to be additional support in the form of state funding, Sutton said.

“One big thing would be giving proper funding for schools to be able to afford additional positions. That could be additional school counselors, school social workers, psychologists, advisors. If we have the resources to create those positions, that would help significantly,” he said. “I love my job, but I’m aware there’s a school counselor shortage and I do think a lot of that shortage is the burnout counselors are experiencing, causing them to leave the profession.”

Without additional education funding or legislation requiring a minimum number of counselors, school administrators are faced with a choice: more teachers or more counselors, Poston said.

“I think if it was mandated we have counselors at every level, it would make a difference, but so much of it is funding. We have a certain allotment of money to hire staff. If we look at teachers and making class sizes smaller, most people will want to put that toward teachers,” she said. “When budgets are so tight, we have to make those decisions.”

Student-to-school counselor ratios in Johnson County

American School Counselor Association recommendation: 250:1

Center Grove: 628:1

Clark-Pleasant: 456:1

Edinburgh: 403:1

Franklin: 390:1

Greenwood: 656:1

Indian Creek: 690:1

State Average: 694:1

Source: Johnson County schools