While Johnson County’s sporting history doesn’t cover the entire 200 years of its existence, we do have well over a century of legendary moments to brag about. From 1912, when Franklin played in the second boys basketball state championship game, through the magical run of the Wonder Five in the 1920s at Franklin High and Franklin College, leading up to the current dominance of Center Grove football, the county has been making waves both on a state level and nationally.

Much of that history has already been well documented. We know plenty about Fuzzy Vandivier, one of Indiana’s first hardwood legends and an inductee into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, and Franklin’s Wonder Five. Much has been written about George Crowe, who was Indiana’s first Mr. Basketball and went on to play professional baseball for a decade.

Rather than rehash the usual statistics and other highlights about such luminaries, we decided to look back at the past from a different angle. We asked a handful of the county’s longest-tenured sports figures to share their favorite local memories — some of them recent, others not so much. (And no, there won’t be any reminiscing about the 1920s and 1930s — there are certain drawbacks to only being able to interview the living — but a trip to the Johnson County Museum of History can help fill in some gaps there.)

The golden age

The county has a storied basketball history dating back more than a century, and Jim Higdon has been around to see more than half of it. A 1968 Greenwood graduate who played basketball and baseball, he has seen almost 2,500 Indiana High School basketball games over the last 60-plus years and didn’t miss a single county tournament game until the first-round games were split up at different sites when Greenwood Christian was added.

Higdon was an assistant coach at Franklin for 28 seasons before spending seven at Whiteland and the last four at Edinburgh. He has vivid memories of everyone from the older Jon McGlocklin, who graduated from Franklin in 1961 and won an NBA championship with the Milwaukee Bucks a decade later, to recent Center Grove star Trayce Jackson-Davis, who is entering his first pro season with the Golden State Warriors.

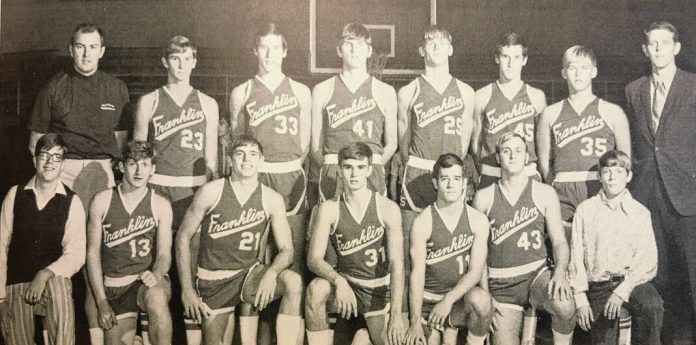

For his money, the period from 1960 through 1974 — especially the early ’70s — was the pinnacle of Johnson County boys basketball. Hidgon’s alma mater won five sectional championships under coach Jack Nay between 1961 and 1970 and had some equally strong teams in the early ’70s that had the misfortune of running into other iconic squads — Center Grove’s 1972 regional champion, headed up by seniors Guy Ogden and Mike Coffey, and the Franklin powerhouse that won back-to-back semistate titles in 1973 and 1974 behind the McGlocklin twins (Don and Jon), Darrel Heuchan, Ed Trogdon and Garry Abplanalp.

The 1971 Woodmen, led by Indiana All-Star Jerry Nichols, might well have preceded them on that list were it not for some ill-timed bad luck.

“If you’d ask me who were the top five or six players in the county from the ’60s to now, Jerry Nichols would be at the top of the list for me,” Higdon said. “That year, ‘71, everybody thought for sure that Greenwood would get to the semistate, state finals even. You had Jerry Nichols, Mike McClain, Billy Hensley … they had some really good players.

“They only lost a couple of games during the year, and Jerry Nichols — he was an All-State player — hurt his ankle in the second quarter. And when that happened, everything just went downhill. Franklin beat them in the semifinal round, and then Franklin ended up winning the sectional. But I think everybody in Greenwood had their state tickets bought, because they really thought it was going to be a special year for Greenwood. It just didn’t happen.”

Higdon remembers plenty of other top-quality teams from that era, such as Whiteland’s 1967 sectional champion led by Tom Lawrence, Ray Helton and Layman Helton.

“It kind of passed around, you know?” Higdon said.

Watching it grow

Butch Zike was on the Warriors’ 1967 title team, and he’s lived all but six of the last 67 years of his life in Johnson County. He’s seen a whole lot during his time in Whiteland — whether as a multi-sport athlete, as a coach or during his two stints as athletic director — and watched the school transform from a 500-student rural engine that could into a rapidly diversifying 2,000-student behemoth about to undergo a massive building overhaul.

He’s had too many fond memories to count, but some of Zike’s favorites came in the spring of 1985, when he coached the Whiteland baseball team all the way to the state semifinal at Bush Stadium in downtown Indianapolis. Just as it did last fall when the Warriors made the Class 5A state title game in football, the entire community came along for the ride.

“When we won the semistate down in Jasper, we had 1,200 people for a pep rally at 2 o’clock in the morning when we got back,” Zike recalled. “The gym was packed. They sold over 3,000 baseball tickets to the state finals in 1985, and did that within about a day and a half.”

Zike admits he didn’t have such high hopes for that team at the start of the season.

“We were 32-5, and the first game I came home and told my wife — I think Martinsville beat us 9-1 — I said, ‘This is going to be a long year.’ I didn’t know long meant extra time.”

Now a member of the Whiteland school board, Zike has worked hard to maintain the small-town feel that he grew up with, even as the high school has grown into one of the state’s largest.

“Everybody knew everybody,” Zike said. “We were a close-knit little town; everybody took care of everybody. … We have tried to keep that.”

Pioneering spirit

Tom Deer — who covered sports for the Daily Journal off and on for nearly two decades and still possesses an encyclopedic knowledge of the last half century of county athletics — was a 1973 Center Grove graduate, so he found it a bit funny to hear himself praising the city of Franklin for its rich basketball history.

An unsung part of that history, he says, is the community’s role in helping to grow the game of women’s basketball.

The IHSAA held its first girls state tournament in 1976, and Warsaw won the championship behind guard Judi Warren, the state’s first Miss Basketball. Warren then came to play at Franklin College, where she helped lead the Grizzlies to three Indiana Women’s Intercollegiate Sports Organization championships (the NCAA wasn’t yet holding women’s tournaments).

Franklin College landing the state’s top high school player now would be a shocker, and to some extent it was back then too.

“Here you had the first Miss Basketball, wound up at little Franklin College, which was offering some athletic scholarships — was a pioneer in offering athletic scholarships for women,” Deer said. “Women’s sports were so primitive back then, she wasn’t really being recruited by much of anybody.”

Countless female athletes in the years since have been influenced by Warren and her Grizzly teammates. Kathy Stricker, a multi-sport star, became the first and only softball coach at Franklin Central. Perhaps best known in this county for her contentious rivalry with the late Russ Milligan and his Center Grove teams, Stricker was inducted into the Indiana High School Coaches Hall of Fame in 2017. Becky Buening — who became a hardwood star at Franklin College despite her high school (North Decatur) not even having a team in the mid-1970s — is a cousin of current Franklin senior basketball player Erica Buening, who helped power the Grizzly Cubs to the Class 4A state championship game in 2022.

Those women, along with longtime Center Grove coach and administrator Carol Tumey, were among those at the forefront in growing girls high school sports in Indiana.

Vandivier brought Warren and Crowe — the first Mr. and Miss Basketballs in Indiana — together for a photograph in the Daily Journal office at some point in the late 1970s, but the moment appears to have largely flown under the radar.

“Unfortunately, there wasn’t anybody sports-oriented there (that day),” Deer said.

Road warriors

The baseball coach at Franklin College since 1997 and the school’s new athletic director this year, Lance Marshall has seen his fair share of great moments since his arrival. Some have come as a spectator — his daughter Addie starred on the soccer field at Franklin and is now a goalkeeper at Butler — but most have been viewed from the dugout. Marshall’s Grizzlies won a regular-season game at Notre Dame in 2007, made their first NCAA Division III tournament appearance in 2011 and had the nation’s best winning percentage in 2018 while putting up some absurd offensive numbers.

When asked to single out a favorite, though, Marshall landed on his 2019 team, which traveled to Texas for an NCAA regional and posted three wins over nationally ranked teams (including two wins over fourth-ranked Trinity) during the deepest postseason run in program history.

“The ‘19 team really kind of put things in perspective like, ‘You guys can win at this level. You’ve just got to play well when it matters,’” Marshall recalled.

The team had a long trip that began with a flight into San Antonio; the Grizzlies had lunch on the Riverwalk and visited the Alamo before driving 25 minutes to Seguin, home of regional host Texas Lutheran.

But it wasn’t necessarily the games themselves that stick with Marshall the most.

“One of my fondest memories — our leadoff guy, Quenton Wellington, goes 5 for 5 against Trinity, the No. 4-ranked team in the country, and his prize for that was to go back to the Holiday Inn Express ballroom and take two final exams,” the coach said. “‘Way to go, buddy — you’re the best player on the planet. Go take these two finals.’

“I think the bonding those guys had was just incredible. They were really close-knit because of the run the year before in ’18, and they kind of pulled it together in ‘19 and were probably even better.”

Supreme on the court

Johnson County didn’t have much tennis history to speak of before the late 1960s; Franklin was the only county high school fielding a team until Ralph Clingerman, working as a student teacher at Greenwood, helped start a program there. He then got a full-time teaching job at Center Grove and created a coed tennis club there in the spring of 1971. (Deer was on the Trojans’ first boys team.)

“Very few schools had tennis courts at the school,” Deer said. “In most cases, the tennis teams played in city parks. Well, here at Center Grove, we had no city, we had no park — so we’d go to Craig Park, an old park in Greenwood, and there were actually two courts in Whiteland by the middle school. We’d practice wherever, and we never played a home match while I was in high school.”

Ivan Smith took over as the Center Grove boys coach in 1977, and it didn’t take long for the Trojans and the rest of the county teams to make their mark. By the fall of 1985, both Center Grove and Greenwood were ranked in the top six of the final regular-season poll before meeting in the sectional.

The Trojans have won 32 regional championships, the fourth highest total in the state, and claimed state titles in 2001 and 2008 under Smith, the state’s all-time winningest tennis coach.

Of the 157 Indiana High School Tennis Coaches Assocation Hall of Fame inductees, Smith was able to count 13 with Johnson County ties, including Center Grove girls coach Debby Burton and longtime Franklin coach Rusty Hughes.

“Per capita, that has to be almost at the top of Indiana, I would think,” said Smith, who perhaps unsurprisingly didn’t remember himself as he and Deer tried to recall all of the local honorees. “More so than probably any other sport. And it didn’t start until the ’70s.”

Constant change

Noel Heminger played four sports at Franklin before graduating in 1968 (the same year as Higdon and Zike). He went on to play baseball and football at Eastern Illinois before returning home to spend 37 years as a coach and athletic director; the Grizzly Cubs’ athletic complex is named for him.

Still an active fan who enjoys watching his grandchildren compete in various sports, both in Franklin and in suburban Chicago, Heminger has watched Johnson County — and the sports world as a whole — transform over the past two or three generations.

“A lot of things have changed,” Heminger said. “There’s so much now for kids to do; sometimes, I think, too much. … I was at Grand Park last week watching one of my grandsons play baseball, but we used to play wiffle ball in the back yard and shoot hoops with gloves on.”

An assistant coach for Franklin’s 1973 and 1974 boys basketball teams when he “was just a young punk,” Heminger bridges the gap all the way through to the most recent generation of Grizzly Cub athletes — one of whom he can still remember as a waist-high ballplayer with a dream.

“When I was coaching (baseball) up there at Crowe Field,” Heminger recalled, “I could hear something hitting the back of the dugout. … Max Clark was out there throwing baseballs on back of the dugout.”

Clark, of course, became the county’s most recent professional athlete this summer when he was chosen third overall in the MLB draft by the Detroit Tigers.

Looking ahead

While Johnson County’s sports history over the past century-plus — from Vandivier to Clark and countless others in between — is rich, it could well be dwarfed by what happens over the next 100 or so years. Local populations have skyrocketed, and athletic opportunities in everything from football and basketball to golf, tennis and swimming are more abundant than they have been at any time in the past, especially for young women.

The payoff is already coming. We had two county football teams play for state championships last fall and another in boys soccer; five different county high schools have at least advanced to a semistate in the last two years. Center Grove alone has claimed 20 team state championships, with 13 of those coming in just the last 15 years.

Five county athletes in four different sports embarked on pro careers just this past summer (Clark, Jackson-Davis, golfers Erica Shepherd and Sam Jean and softball star Jordyn Rudd). Surely more — some now playing youth soccer or softball for the first time, some not even born yet — will follow in the near and distant future.

Their stories remain unwritten, to be told by a future generation.

Who knows? Maybe there will still be a local newspaper around to tell them.