DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — The United States has quietly acknowledged that Iran’s paramilitary Revolutionary Guard successfully put an imaging satellite into orbit this week in a launch that resembled others previously criticized by Washington as helping Tehran’s ballistic missile program.

The U.S. military has not responded to repeated requests for comment from The Associated Press since Iran announced the launch of the Noor-3 satellite on Wednesday, the latest successful launch by the Revolutionary Guard after Iran’s civilian space program faced a series of failed launches in recent years.

Early Friday, however, data published by the website space-track.org listed a launch Wednesday by Iran that put the Noor-3 satellite into orbit. Information for the website is supplied by the 18th Space Defense Squadron of the U.S. Space Force, the newest arm of the American military.

It put the satellite at over 450 kilometers (280 miles) above the Earth’s surface, which corresponds to Iranian state media reports regarding the launch. It also identified the rocket carrying the satellite as a Qased, a three-stage rocket fueled by both liquid and solid fuels first launched by the Guard in 2020 when it unveiled its up-to-then-secret space program.

“Noor” means “light” in Farsi, while “Qased” means “messenger.”

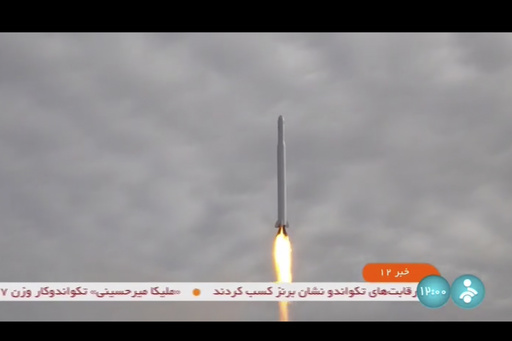

Authorities released a video of a rocket taking off from a mobile launcher without saying where it occurred. Details in the video earlier analyzed by the AP corresponded with a Guard base near Shahroud, about 330 kilometers (205 miles) northeast of the capital, Tehran. The base is in Semnan province, which hosts the Imam Khomeini Spaceport from which Iran’s civilian space program operates.

The website space-track.org also listed the missile as having been launched from the Guard base at Shahroud.

Speaking Thursday night to Iranian state television, Guard space commander Gen. Ali Jafarabadi described the Noor-3 satellite as having “image accuracy that is two and a half times that of the Noor-2 satellite.” Noor-2, launched in March 2022, remains in orbit. Noor-1, launched in 2020, fell back to Earth last year.

Jafarabadi said Noor-3 has thrusters for the first time that allow it to maneuver in orbit. He also offered a wider description of Iran’s hopes for its satellite program, including potentially controlling drones. That could raise further concerns for the West and Ukraine, which Russia has bombarded with Iranian-made bomb-carrying drones for over a year.

“If you look at the recent wars in the world, you will see that success on the battlefield is very dependent on the use of satellite technologies,” Jafarabadi said. “Now the armed forces in all the progressive countries are trying to make all their equipment remote control, it means that to make it steerable, when a vessel or any other equipment takes a long distance from us, it is no longer possible to see and guide it, except through satellite.”

The image-taking capabilities of the Noor-3 remain unclear. International sanctions on Iran have locked it out of accessing commercially available imagery, forcing it to develop its own homegrown satellites. The head of the U.S. Space Command dismissed the Noor-1 as a “tumbling webcam in space” that would not provide vital intelligence.

The United States says Iran’s satellite launches defy a U.N. Security Council resolution and has called on Tehran to undertake no activity involving ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear weapons. U.N. sanctions related to Iran’s ballistic missile program are due to expire Oct. 18.

The U.S. intelligence community’s 2023 worldwide threat assessment says the development of satellite launch vehicles “shortens the timeline” for Iran to develop an intercontinental ballistic missile because it uses similar technology.

“Iran’s continued advancement of its ballistic missile capabilities poses a serious threat to regional and international security and remains a significant nonproliferation concern,” U.S. State Department spokesperson Matthew Miller said Thursday. “We continue to use a variety of nonproliferation tools, including sanctions, to counter the further advancement of Iran’s ballistic missile program and its ability to proliferate missiles and related technology to others.”

Iran has always denied seeking nuclear weapons and says its space program, like its nuclear activities, is for purely civilian purposes. However, U.S. intelligence agencies and the International Atomic Energy Agency say Iran abandoned an organized military nuclear program in 2003. The involvement of the Guard in the launches, as well as it being able to launch the rocket from a mobile launcher, also raise concerns for the West.

Over the past decade, Iran has sent several short-lived satellites into orbit and in 2013 launched a monkey into space. The program has seen recent troubles, however. There have been five failed launches in a row for the Simorgh program, another satellite-carrying rocket.

A fire at the Imam Khomeini Spaceport in February 2019 killed three researchers, authorities said at the time. A launchpad rocket explosion later that year drew the attention of then-President Donald Trump, who taunted Iran with a tweet showing what appeared to be a U.S. surveillance photo of the site.

Tensions are already high with Western nations over Iran’s nuclear program, which has steadily advanced since Trump five years ago withdrew the U.S. from the 2015 nuclear agreement with world powers and restored crippling sanctions on Iran.

Efforts to revive the agreement reached an impasse more than a year ago. Since then, the IAEA has said Iran has enough uranium enriched to near-weapons grade levels to build “several” nuclear weapons if it chooses to do so. Iran is also building a new underground nuclear facility that would likely be impervious to U.S. or Israeli airstrikes. Both countries have said they would take military action if necessary to prevent Iran from developing a nuclear weapon.

Iran and the U.S. just conducted a prisoner swap in which South Korea released just under $6 billion in frozen Iranian assets. However, both countries have signaled publicly that they are no closer to any wider diplomatic deals.

___

Associated Press writer Amir Vahdat in Tehran, Iran, contributed to this report.

Source: post