People had flocked from 40 states and four different countries for a celestial equivalent of winning the lottery — a total solar eclipse.

Hotels were sold out for miles around Paducah, Kentucky. Roads were packed with cars as people arrived for the weekend and made their way around town. Community festivals and viewing events were filled.

After years of preparations, Paducah found itself in the center of a tourism maelstrom.

“For residents, take full advantage of everything the city has to offer,” said Liz Hammonds, director of marketing and communications for the Paducah Convention & Visitors Bureau. “Experience your city like a tourist might. Sometimes, in any city, your residents don’t quite realize what they have in front of them.”

Paducah and other communities that experienced 2017’s total solar eclipse offer a roadmap of what Johnson County can expect on April 8. Certainly, with tens of thousands of visitors scoping out places to stay, restaurants to eat at and things to do, some logistical headaches are sure to happen.

But at the same time, the event offers a unique opportunity to impress visitors, and entice them to come back.

“We feel that we’re as prepared as possible to provide residents and visitors with an enjoyable experience,” said Kenneth Kosky, executive director of Festival County Indiana, the county’s tourism organization.

On Aug. 21, 2017, the path of a total solar eclipse dubbed the “Great American Eclipse” passed across the country from Oregon to South Carolina.

According to a research paper published in 2022 in the journal Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, about 21 million people traveled to another city to view the event.

Among the communities that were in the path of totality was White House, Tennessee. The city of about 13,000 people is located about 30 minutes north of Nashville, and spent approximately two minutes 39 seconds in totality in 2017.

Mandy Christenson, executive director of the White House Area Chamber of Commerce, spoke to local leaders during a webinar hosted by Aspire Johnson County on Feb. 28. Her recommendation was for local businesses and residents to take advantage of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

“Businesses should be really creative and capitalize on the amount of visitors who are coming to your community — because they are coming,” she said during the webinar.

In the two years leading up to the 2017 eclipse, Christenson admitted she didn’t understand what the hype was about the event. Looking back, it truly was a monumental experience that local officials need to plan for.

“Once you experience it, you’ll understand it. That’s what a lot of our community said,” she said.

Much of southern Illinois also found itself in the path of totality in 2017. Much of the area is dominated by the Shawnee National Forest, state and local parks, so officials prepared campgrounds and impromptu venues for a mass of visitors. Places such as Camp Ondessonk, a Catholic youth camp located in the path, welcomed thousands of people on the day of the eclipse.

Other places, such as Carbondale, hosted community festivals for the event.

The main issue was congestion as everyone tried to leave after the eclipse, said Carol Hoffman, executive director of Shawnee Forest County, the Southernmost Illinois Tourism Bureau.

The recommendation would be to avoid it if you don’t have to be on the roads. Hoffman’s office is encouraging people to leave later in the day after the eclipse is done, or consider staying an extra night.

“For many people, a six-hour drive became a 20-hour drive,” she said in an email.

Similar advice comes from Paducah’s experience. In the lead-up to the 2017 eclipse, community leaders banded together in preparation for the influx of visitors. Officials were confident they had enough hotel rooms to handle the visitors; about 2,200 rooms were available around town.

The city hosts conferences throughout the year, and its QuiltWeek every April is one of the country’s largest quilting festivals.

“That hotel room stock was something we were prepared for,” Hammonds said.

Local officials also worked with Kentucky Emergency Management, which was spearheading preparations across the 21 counties encountering the eclipse. They warned about gridlock overwhelming interstates and highways in the area, including along Interstate 24, which runs through the heart of Paducah.

But while community officials wanted to be ready from a safety standpoint, they also aimed to use the exposure to impress new visitors. They planned public festivals and events, such as a hillside viewing party hosted by the Western Kentucky Community and Technical College. More than 3,000 out-of-state attendees took part, Hammonds said.

“The most important thing for us was working closely with our partners. The (conventions and visitors bureau) worked with hotels, restaurants, retail shops. Paducah has a lot of culture and artistic attractions, so we worked closely with them,” she said. “If I was to give any other city advice, it would be to rely on your partners, communicate with them and realize this is a partnership.”

Coincidentally, both the Carbondale, Illinois, area and Paducah once again find themselves in the path of totality in 2024. Officials in both locations are using the lessons learned seven years ago to prepare for this one.

Kentucky safety officials are predicting about 150,000 visitors just to western Kentucky.

“Spectators are encouraged to come early and stick around after the event to reduce the potential for hours-long gridlock that’s possible when a wave of thousands of drivers return home after the event,” said Jim Gray, Kentucky Emergency Management secretary. “Similar to a severe snow event, motorists should travel with an emergency car kit stocked with essential items for all passengers. It’s also a good idea to bring printed directions to your destination if there are cell service disruptions that impact your navigational apps.”

As Johnson County leaders have been preparing, they’ve leaned on advice of others with eclipse experience to get ready for the 2024 event.

Shortly after the 2017 eclipse, Kosky attended a conference hosted by Destinations International, the international organization for tourism groups. One of the presentations he attended focused on cities in the path of the 2017 eclipse, and what communities can learn for 2024.

He later had conversations with the lead presenter, Brook Kaufman, who led eclipse efforts for Casper, Wyoming, in 2017, while speaking with other communities as well.

The research led to a plan of action, including securing a website domain, eclipsefestival2024.com, as well as purchasing more than 100,000 pairs of eclipse glasses, reaching out to churches, schools, cities, towns and attractions to host eclipse events, and providing grants to fund community events on eclipse weekend, Kosky said.

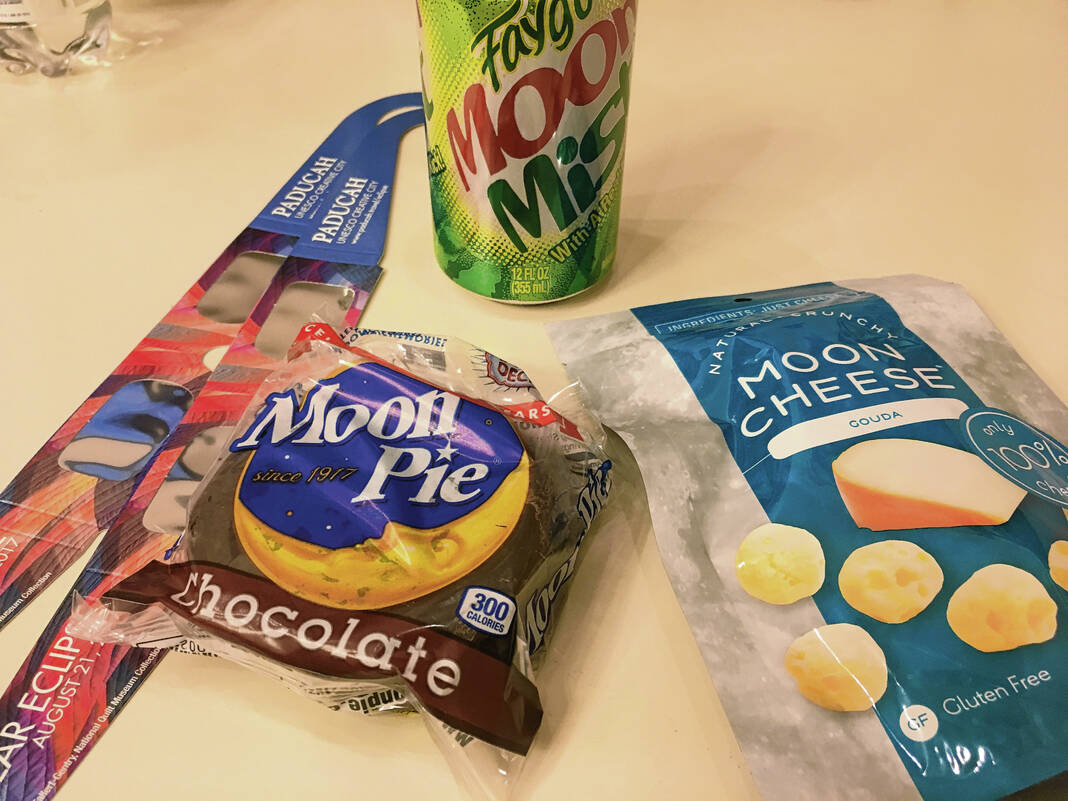

They also worked with our restaurants and shops to encourage them to be open and have simple, eclipse-themed menus and to sell souvenirs.

“Based on what I learned, Festival Country Indiana was able to get started planning for this historic event six years before it was to happen,” Kosky said.

ECLIPSE 101

A solar eclipse happens when, at just the right moment, the moon passes between the sun and earth. Sometimes it only blocks part of the sun’s light (partial solar eclipse), but sometimes it blocks all of the light (total solar eclipse). The moon casts a shadow on a narrow part of the earth, and this shadow trail is what is called the path of totality. Within that path, the moon blocks the sun completely for up to a few minutes.

Find a place to watch from and get there early

The total solar eclipse will be highly publicized in the days leading up to April 8. Because of the rarity of total solar eclipses, many thousands of people will be traveling to Indiana or from elsewhere within the state so that they can be in the path of totality. In fact, it is estimated Indiana may see as many as half a million out-of-state visitors for the eclipse, boosting the state’s population by nearly 10%.

This will lead to unusually high levels of traffic on roadways. To avoid being on the roads at these times, plan ahead:

- Look up a location nearby that is in the path of totality.

- Make sure that you find a spot with a good view of the sky — not obscured by trees or other tall objects.

- Be sure that you have permission to watch from a location; Many places are hosting events where the public can watch.

- Make arrangements to arrive there before peak travel occurs.

Time it right

The eclipse will begin at approximately 1:45 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time on April 8 and end at about 4:30 p.m. Totality is the most special stage of the eclipse and is the only period of time when you can observe the total eclipse without eclipse glasses. This stage will begin shortly after 3:05 p.m. in Johnson County and will last until about 3:10.

Stay around

The time of totality will be over by 3:15 p.m. in Indiana, and the partial eclipse will be completely over by 4:30 p.m. Plan ahead to stay at the location you viewed the eclipse for a while to allow for peak traffic to pass. Consider staying the night there instead of leaving immediately after the eclipse.

— Information from the Indiana Department of Homeland Security

Editor’s note: A photograph of the 2017 eclipse over the Cache River Basin that was originally on this story has been removed. The image removed was an altered, promotional image for eclipse-themed canoe rides provided by Southernmost Illinois Tourism Bureau. Had we known the image was altered it would not have been published. The source did not provide this information when sharing the photo.

The Daily Journal adheres to strict ethical policies with our photos. Typically and according to industry standards, the only editing tolerated is slight cropping to better focus on the subject of the photograph, and slight color adjustments that don’t materially change the image.