Anticipation is building for the April 8 total eclipse, which promises to be a boon for scientists.

But many people still likely have questions about the natural phenomenon, how it works and how it will affect animals.

Scientific experts answered questions about these topics, along with the social science behind the events, during a SciLine media briefing Tuesday. Here’s what they had to say.

Q: Why don’t eclipses occur all the time?

Part of the reason behind why there aren’t solar eclipses all the time is because the moon’s orbit around the Earth is tilted by about five degrees. Because of this tilt, the shadow moon casts goes in between the Earth and sun, missing the Earth, said Dr. Shannon Schmoll, director of the Abrams Planetarium at Michigan State University.

However, in a different orientation where the moon is between the Earth and sun, crossing the plane of the Earth’s orbit, it ends up having the moon cast a shadow on the Earth. In this orientation, there is a 34-day window where as long as there’s a new moon, a solar eclipse will occur, Schmoll said.

“Since the moon takes less than 34 days to go around the Earth, typically we end up with about two a year,” she said.

Q: What science can be done around the eclipse?

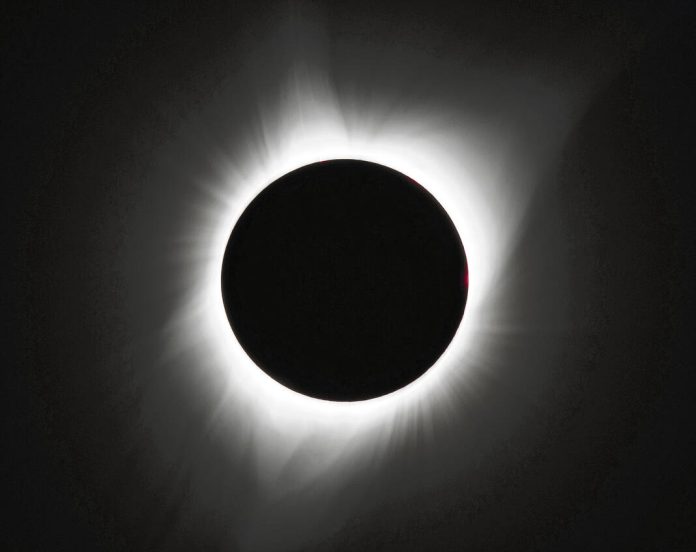

Scientists will study the sun itself and its outermost atmosphere, the corona. This is a really hot region of the sun, but scientists don’t fully know why it is, Schmoll said.

They can’t see the lowest part of the corona very well most of the time, even with the spacecraft available now. So the eclipse is a great time to study this region, she said.

The sun is also approaching its solar-maximum, an 11-year cycle where a lot more activity happens on the sun. It was near the minimum during the last eclipse, so scientists will have more to look at this time around, Schmoll said.

It’s also a great time to study the Earth and the effects the sun has on the planet, she said.

Q: How will it affect animals?

Based on published accounts, researchers often see animals start nocturnal, or nighttime, behaviors during eclipses. For example, crickets start chirping, bats start emerging or birds go on to roost, said Dr. Andrew Farnsworth, a visiting scientist in the Center for Avian Population Studies at the Cornell University Lab of Ornithology.

These patterns are important to for understanding the way animals perceive their worlds, Farnsworth said.

“We know that light is a very powerful stimulus for many animals,” he said. “It can train certain kinds of behaviors, that means it brings them about; it’s associated with them.”

Using weather radar data from the 2017 eclipse, researchers found a decrease in the number of animals flying around during an eclipse. However, the decrease was not down to the level typically seen at sunset, Farnsworth said.

“What we’re seeing here is that the eclipse is strong enough to suppress that daytime, diurnal activity of flying insects and birds going to roost,” he said. “But it’s not strong enough to initiate the kind of typical nocturnal behaviors we see at sunset, in particular during that August eclipse, for birds migrating, more bats emerging.”

Since this year’s eclipse will go over more U.S. radar sites than in 2017, Farnsworth and other scientists hope to get more data on how flying animals react during eclipses, he said.

Q: How do eclipses affect people psychologically?

After the 2017 eclipse, researchers looked for shifts in how people talked about themselves, their motivations and fellow humans — comparing results from residents in and outside of the path of totality who experienced the eclipse.

What they found was that people in the path of totality became less self-focused, less likely to talk about themselves and more likely to use collective pronouns like “we” or “us.” They also expressed more desires to connect and affiliate with others and became more “pro-social” — exhibiting an increased tendency to be kind or care for others, said Dr. Paul Piff, an associate professor of psychological science at the University of California-Irvine.

“What we’re finding is that experiences that bring about awe — and most predominantly really powerful fleeting experiences like the solar eclipse — seem to attune people and connect us to one another, connect us to entities that are larger than ourselves,” Piff said. “In part we think that that’s how the experience of awe might have evolved. It’s the conduit to entities larger than us, it connects us to things bigger than ourselves, motivates us to care for others and the greater good.”

The feelings lasted for up to six weeks before going down to the baseline Piff and other researchers recorded the residents starting with, he said.

Q: How have eclipses impacted societies throughout history?

There are numerous historical accounts of eclipses throughout history.

Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian, talked about an eclipse having ended a six-year war between the Medes and the Lydians, Piff said. This eclipse occurred in 585 BC, according to historical records.

Other accounts are more “apocryphal.” It’s been reported that soldiers dropped their weapons and became “absolutely adamant” about coming to a truce, he said.

“Maybe you could say that that experience of wonder sort of eclipsed whatever human factors might have been giving rise to the antagonism they’re experiencing,” Piff said.

Eclipses have also been reported to inspire the works of Shakespeare in King Lear. The emergence of new scientific fields has also been tied to certain eclipse events, Piff said.

“[The eclipse] certainly seems to fuel a creative impulse within our species,” he said.