Medicaid rolls in the Hoosier State are higher today than they were in February of 2020, more than four years after the emergence of COVID-19 and accompanying federal health coverage protections.

But outcomes for disenrolled Hoosiers are still unknown.

With 11 of 12 months posted — and the last due to publish in the coming days — the Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA) wrapped up the yearlong redetermination process in April.

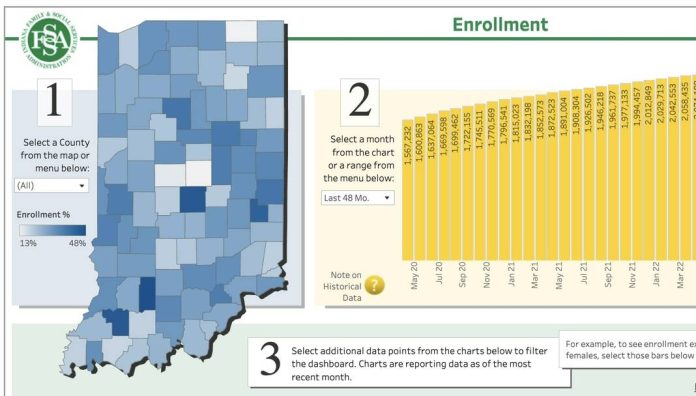

Nearly 2 million Hoosiers rely upon Medicaid for their health coverage, compared to 1.5 million in February 2020. Enrollment peaked at 2.3 million beneficiaries in April 2023.

“Having a global pandemic made Hoosiers poorer and sicker,” said Tracey Hutchings-Goetz, the communications and policy director for advocacy group Hoosier Action. “It should not come as a surprise that that’s what happened, but I think that’s an easy thing to miss.”

“In the wake of a health crisis, of course they need health care and, of course, people are struggling more economically,” Hutchings-Goetz continued. “It really highlights how essential these services and programs are for people.”

FSSA Director of Communications and Public Affairs Michele Holtkamp said the office had delivered on the promise “to be resolved in trying to reach Hoosiers who hadn’t completed a redetermination process in four years, if ever.”

“We were committed to being really transparent about our data,” Holtkamp said. “… being as transparent as possible, as early as possible, really helped in lots of ways. We were able to build trust with stakeholders (and) it allowed for accurate comparisons with other states who are going through similar processes.”

Indiana’s disenrollment rate is near the national average: 30% for Hoosiers compared to 31% across all states, according to the KFF Unwinding Tracker. Indiana is slightly ahead of other states in its unwinding process because it started redeterminations in May 2023. The bulk of states started in either June or July.

The unwinding process

During the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic tumult, the federal government incentivized states to keep every beneficiary continuously enrolled in Medicaid by shouldering an additional percentage of costs. By Indiana paying less on coverage and not spending funds on routine eligibility checks, the state actually saved money even though more Hoosiers were enrolled in the program and getting the benefits of health care coverage.

The federal government returned to normal operations in early 2023, triggering the “unwinding” of coverage protections and allowing states to start the redetermining coverage. Between April 2023 and March 2024, roughly 371,000 individuals were disenrolled, according to a Friday Medicaid report. However, 20-25% of those Hoosiers were re-enrolled within 90 days after submitting additional information.

Throughout the unwinding process, both Hutchings-Goetz and Holtkamp said the communication improved between the agency and advocates on the ground.

“We listened to the experiences of Hoosiers. We listened to our employees who are working with them and we listened to the stakeholders in the communities across the state and responded to any concerns or suggestions they raised to the best of our ability,” Holtkamp said.

Hutchings-Goetz said stronger communication allowed for quick responses. For instance, including fixes to jargon-filled letters FSSA sent to beneficiaries.

“I remember early on, I sent them an email to be like, ‘Hey, this date is wrong in this letter. I found this error and it’s confusing.’ And it was fixed within 24 hours,” Hutchings-Goetz said.

Part of that improvement came, she said, from having Hoosier Action members and others attend FSSA meetings and speak up during the public comment period in addition to one-on-one emails.

Advocates initially raised flags early in the process due to the state’s high rate of procedural disenrollments, or so-called paperwork errors, that they worried could deny people coverage when they actually qualified. Early on, Indiana ranked above the national average when 85% of disenrollments were procedural — compared to 75% for all states.

That national average fell to 69% as of last week and Indiana’s percentage sat at 78%, according to KFF’s tracker.

In response to early feedback, Indiana’s Medicaid outcomes dashboard now includes a breakdown of procedural disenrollments. For example, 155,314 Hoosiers were due for renewal in March and 63%, or 97,697, maintained coverage. Three percent, or 4,427 Hoosiers, were determined to be ineligible and another 9,608 were terminated for procedural reasons.

Of those 9,608, more than a quarter — 2,748 — didn’t respond to FSSA’s prompts and were determined to be ineligible through other available data. Another 4,500 didn’t respond and FSSA didn’t have other data available, while the remaining 2,360 provided incomplete information or were confirmed to be ineligible in another way — which might mean the member died or moved out of state.

Those members have 90 days to appeal and could possibly regain their coverage should their new or resubmitted documentation show they are eligible.

Part of the reason disenrollment due to procedural reasons decreased over the months could be that Hoosiers on Medicaid started sharing details with one another and learned from each other’s mistakes. Holtkamp noted that FSSA made a pivot to include relatives or friends of Medicaid beneficiaries in their publicity materials to better spread the word.

Hutchings-Goetz urged Hoosiers weighing their coverage options to utilize a health care navigator, who can help someone discover whether they still qualify for Medicaid or the federal marketplace.

“Medicaid programs are just really complicated. There’s 40-some of them and they’re all branded differently and it can be really confusing for folks,” Hutchings-Goetz said. “There’s often a public education gap where folks don’t know that they don’t have to be in this alone. They don’t know that there’s organizations and individuals out there who can support them.”

Questions, challenges remain

As for the estimated 371,000 Hoosiers no longer enrolled in Medicaid — and the additional beneficiaries who may fall off in the final month of redeterminations — neither advocates nor state officials know what their current coverage status may be.

The state system of Medicaid and the federal marketplace under the Affordable Care Act aren’t linked. So though the state acknowledges that a portion of the ineligible Hoosiers qualify for the marketplace and its federally subsidized health care coverage, no one can yet say how many Hoosiers successfully transitioned.

In January, at the end of the enrollment period, nearly 300,000 Hoosiers had transferred into the marketplace, including first-time users. The only other indicator to follow would be to see if Indiana’s number of uninsured increases as unwinding ends, but those numbers lag behind real-time data.

A study from KFF found that nearly a quarter of those disenrolled said they now lacked coverage, or 23%, though nearly half of the 1,227 people surveyed said they had re-enrolled. Another 28% said they now had another type of coverage, usually employer-sponsored insurance. Over half told KFF they delayed health care while going through the redetermination process.

Another concern for Hutchings-Goetz is the potential return of premiums for some Medicaid members, specifically POWER Account contributions for those enrolled in the Healthy Indiana Plan.

Those who make between 100-133% of the Federal Poverty Level, or between $31,200-41,496 for a family of four, are required to make these contributions in order to stay enrolled. This requirement, which impacts between 14-19% of HIP enrollees, was waived during the COVID-19 pandemic.

FSSA told the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services it intended to reintroduce those premiums sometime this year, a concern for the federal agency.

CMS, in a December letter, noted that between February 2015 and November 2016, over half of all beneficiaries, or 324,840 Hoosiers, required to make POWER contributions missed at least one payment. Of them, 88%, or 286,914, were put onto a more basic insurance plan and 4%, or 13,550, were disenrolled. The remaining 14%, or 46,176, were those who applied for HIP Plus and were accepted but didn’t make the initial payment.

But Hoosiers making up to 150% of the federal poverty level, or $46,800 for a family of four, in the federal marketplace won’t pay any premiums — unlike those in a slightly lower income bracket — after Congress increased subsidies.

CMS’ December letter concluded by saying that the agency would not take action “at this time … to minimize disruptions to the state’s unwinding efforts” but didn’t rule out future action.

By Whitney Downard – The Indiana Capital Chronicle is an independent, not-for-profit news organization that covers state government, policy and elections.