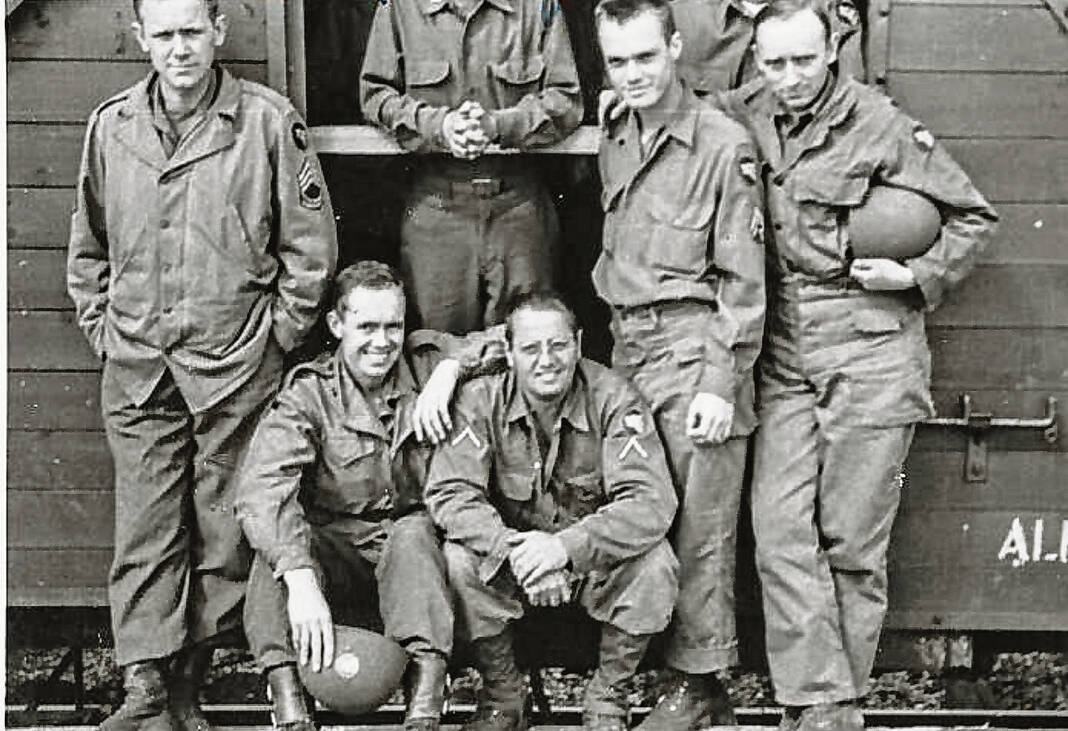

Southside Indianapolis resident Ted Dryer, left, poses with Greg Hill, president of the E.A.A. Chapter 1354 in Greenwood during an event honoring Dryer on June 6. Dryer was a World War II veteran of the U.S. Army, serving in Europe during the war before returning home to work a lengthy career as a civil engineer. He turns 100 on July 16. SUBMITTED PHOTO

What may have disqualified him from serving his country turned into an incredible asset.

As World War II raged, Wilbur “Ted” Dryer joined thousands of his fellow Americans to enlist in the fight. But being blue-green colorblind, he feared he wouldn’t be accepted in the U.S. Army.

Instead, the quirk proved to be an advantage — though he couldn’t see certain colors, he was able to spot camouflaged artillery where other soldiers could not.

The story was one of many Dryer shared during a special gathering of the Experimental Aircraft Association Chapter 1354 in Greenwood on June 6. Members of the association honored his upcoming 100th birthday on July 16 with cake, heard about his service in World War II and saw mementos from his time in the Army.

Throughout his 100 years, Dryer’s got stories to tell — about his time growing up in Indianapolis, serving in World War II in Europe, and of earning a degree as a civil engineer. He helped lead projects building grandstands at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and libraries throughout Indianapolis.

Asked about all of the things that have happened in his life, he said, “It certainly is amazing.”

Dryer was born on July 16, 1924, in Indianapolis — “Right in the middle of the state,” he said. The city was a much different place at the time, even as people were prospering in the times before the Great Depression. His family lived on North Delaware Street in the city, where his father was a carpenter. Dryer attended School 33 before graduating high school at Arsenal Tech.

After school, he enlisted in the Army. He became a tech sergeant with the artillery in the 104th Infantry Division — known as the “Timberwolves” — and would serve out his time in the war in the European Theater. His unique ability to see through camouflage made him an asset as the unit made its way toward Germany.

Together with his fellow soldiers, Dryer was part of one of the Allied forces’ most consequential victories: crossing the Rhine River and reaching Germany at the Battle of Remagen.

When he returned from the war, Dryer took advantage of the GI Bill benefits to enroll at Purdue University, where he graduated with a degree in civil engineering.

“That was a pretty good day,” he said.

For decades, Dryer worked in construction, much of it for Harry D. Tousley Construction Co. The company was a major contributor to structures at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, including an early version of the pagoda at the track and its museum.

Dryer helped lead projects such as building bridges over Interstate 465, constructing the Indianapolis Museum of Art and the dam at Eagle Creek Reservoir.

He ended up retiring three different times — coming back to be a consultant after initially stepping away.

“I really enjoyed my time in construction,” he said.

When he wasn’t working, Dryer enjoyed playing golf and being with family. But few things would be as central to his life as bowling.

As a young man just out of college, he had come back to Indianapolis and gone to a bowling alley to inquire about joining a summer bowling league. The owner of the alley — who would become Dryer’s mother-in-law — said that her daughter needed someone to play on her team.

Dryer readily accepted, only to learn later that his new teammate was Pat Striebeck, a star bowler renowned throughout the country who would later be named to the Indianapolis Bowling Hall of Fame, the Indiana Bowling Hall of Fame and the Indiana and the National Bowling Hall of Fame.

“He’d followed her career and knew who she was,” said Tammy Kelley, Dryer’s daughter. “Bowling has been a big, big part of all of our lives. We traveled all over the country to national tournaments.”

Dryer and Striebeck enjoyed a whirlwind romance; after meeting in May 1952, he proposed to her in July and they were married in December. The couple had two children, Kelley and Steve Dryer.

With his 100th birthday approaching, family members and a few friends have planned a party to celebrate. They had organized a big blow-out for Dryer’s 90th birthday, with about 100 people filling Kelley’s southside Indianapolis home.

One hundred years has brought a wealth of experiences, joys, sorrows and triumphs. Dryer has seen technological advances he never would have imagined as a child.

He still remembers the first time he saw a color television.

“It was pretty impressive,” he said. “That was pretty neat.”