Shortly after opening, the breakfast area in the hotel lobby slowly filled up with sleepy-eyed teenagers carrying backpacks or duffel bags.

Volleyball players. Softball players. Swimmers. Within minutes, each of them was fully fueled up and on their way out the front door to compete.

Whether it’s in Louisville, Nashville, here in the Indianapolis metro area or in some other city or suburb, such scenes are particularly commonplace on summer weekends. Young athletes traveling to various tournaments, meets and showcases to test their skills against the best from other areas around the Midwest and across the country.

Travel sports have become ubiquitous in recent years as more and more families push more and more chips into the center of the table in order to help their children pursue their athletic ambitions.

But has that pursuit gone too far? Are the costs that families pay, both in money and time, worth the benefits?

The answers to those questions depend on one’s individual values and priorities.

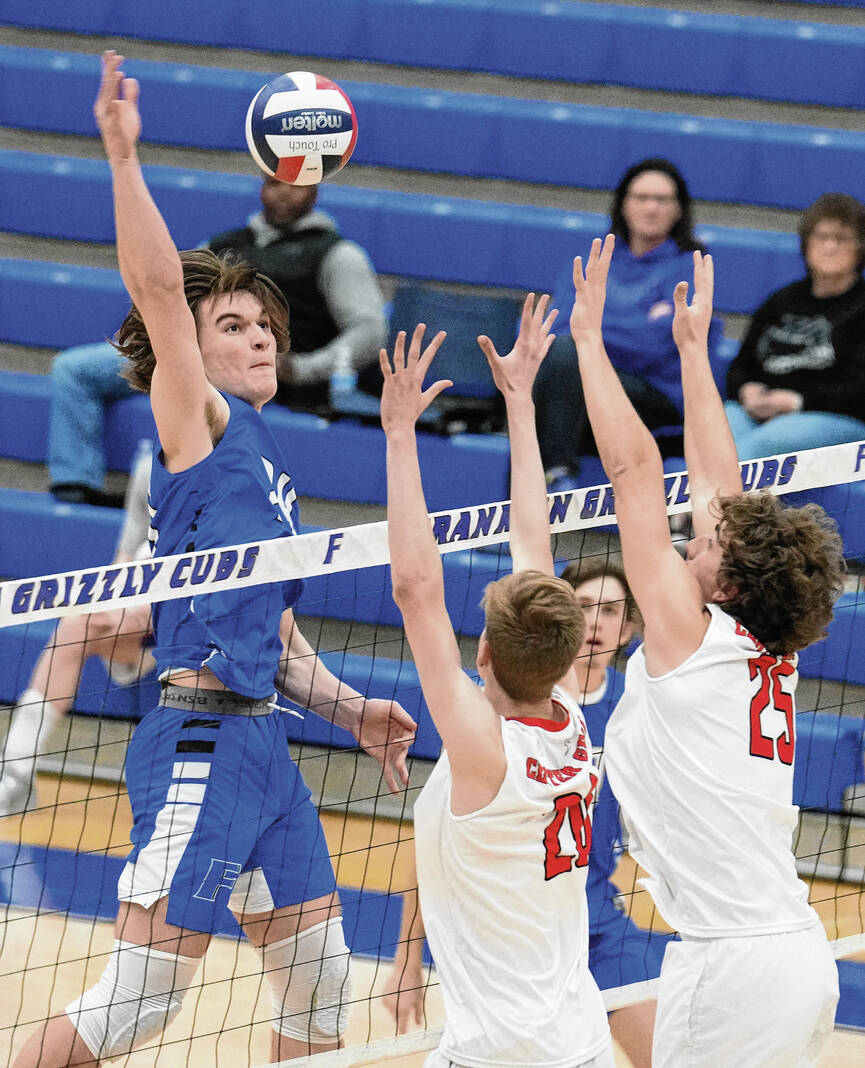

Aimee Alyea had already made two trips to California and two to Florida this year to watch her children — Chase, a senior boys volleyball player at Franklin, and younger sister Charli, a seventh-grade swimmer — compete in their various sports. So when Charli qualified for the Central Zone 14 & Under Championship earlier this month in Fargo, North Dakota, Aimee handed the car keys to her husband, Chris.

“I was kind of over the travel,” Aimee said. “I wanted to be there, but at the same time I felt like one of us needed to be home. (Chris) likes driving, so it kind of worked out perfectly.”

For families with multiple children in different sports, that sort of divide-and-conquer strategy is often a necessity — even just for local practices — when kids’ athletic schedules pull in different directions.

Renna Waalkens, a high school teacher in Whiteland who has three children playing different scholastic and travel sports, says that she has often had to call in the cavalry for assistance to make it all work.

“If we have multiple games in a day, it might take another family picking up one of our kids and getting them there,” she said, “just so they can be there in time for warmups, but then we’re able to — one of us, at least, is able to make from game to game.

“We try to see as much as we can, and when it all works out, it is magical.”

The bigger magic trick these days, though, is the ability of travel sports to make a family’s money disappear. Not every school sports team charges participation fees, but the costs of competing for a club team outside of school can become exorbitant.

According to the Aspen Institute’s annual “State of Play” report, nearly half of survey respondents (49%) said that they struggle or have struggled to afford the participation costs for their children’s youth sports programs. The average annual cost for a child’s primary sport in the United States was $883 in 2022, with Americans spending an estimated total of $30 to $40 billion a year on youth sports.

And that’s just the base cost; when out-of-town or out-of-state travel comes into play, the expenses can skyrocket. Gas or plane tickets, hotel rooms, eating out while on the road — even a quick weekend jaunt to Louisville or another nearby city ends up costing a family well over $500.

Such trips can add up quickly.

For some, the total cost of having a child on a high-level travel sports team can run upwards of $10,000 annually. And when the price tag gets that high, some can start to view those payments as an investment — with the expectation that it will pay off in the form of a college scholarship.

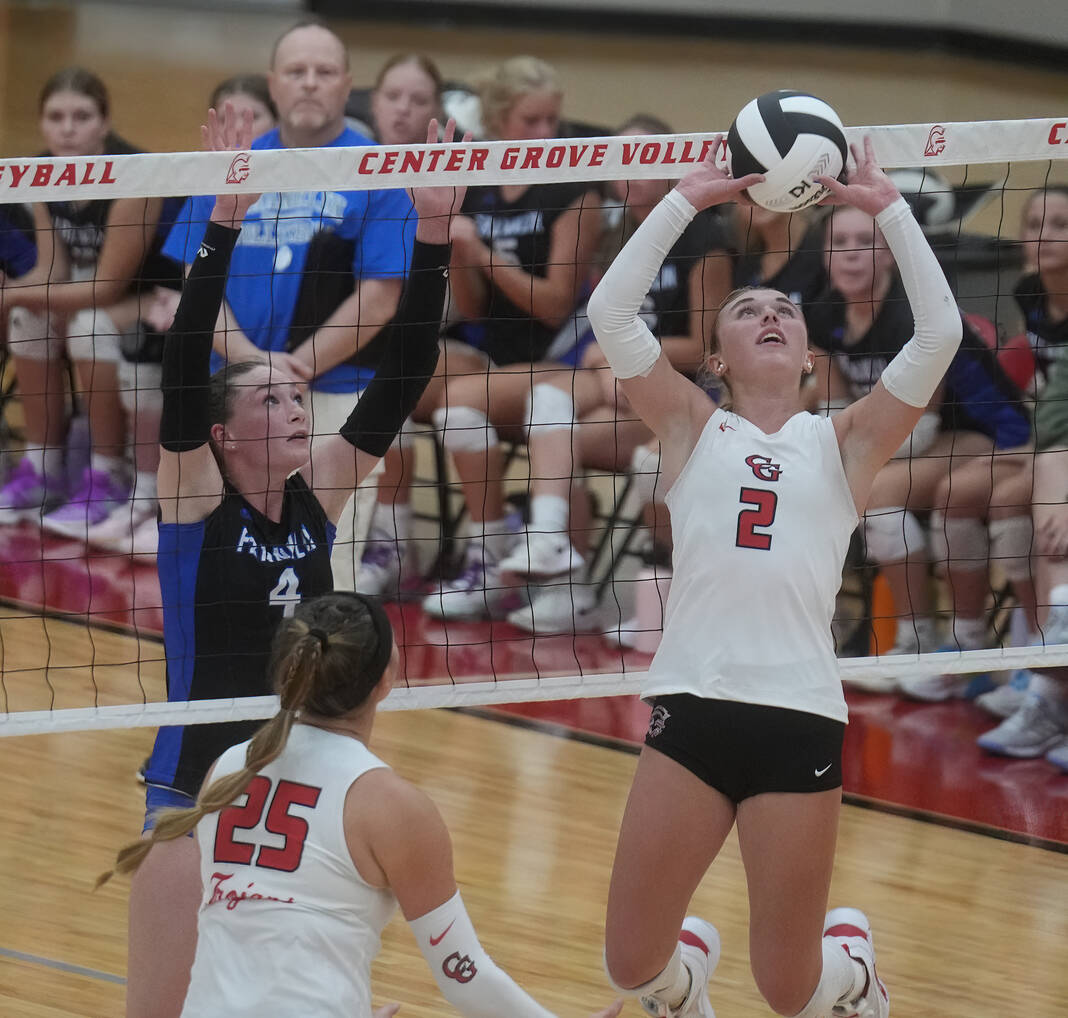

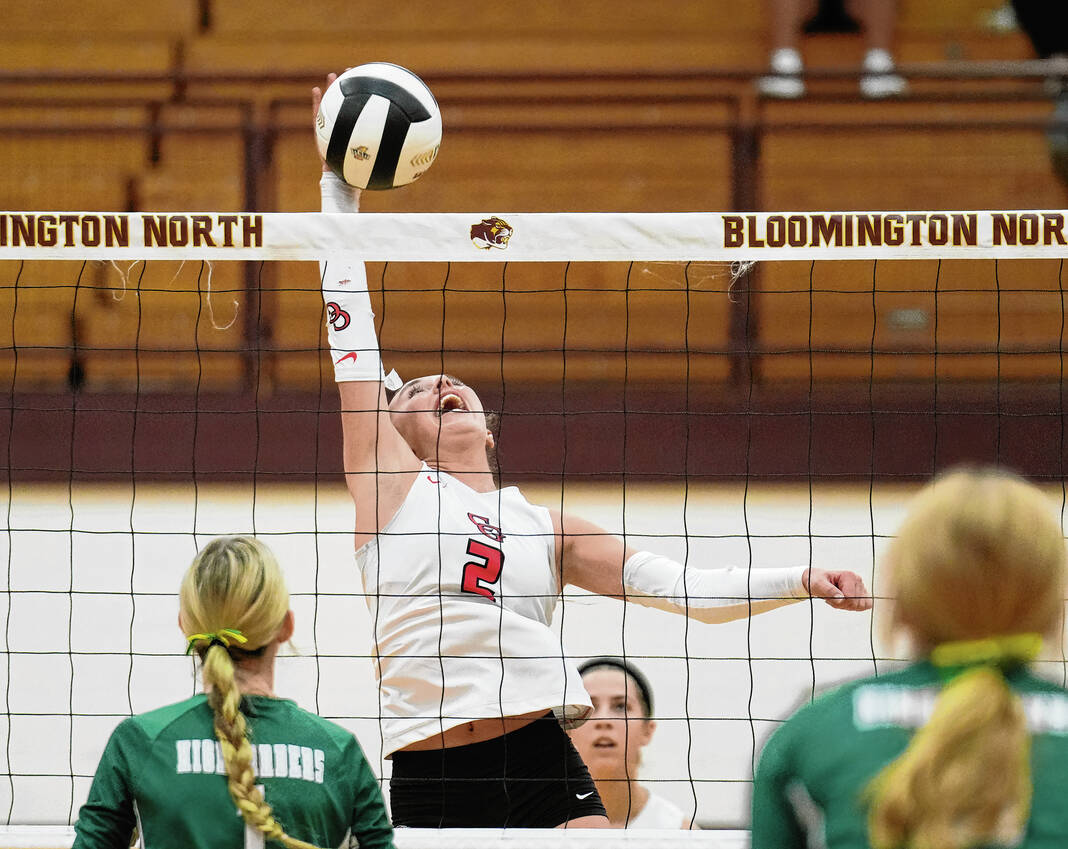

Delanie Owen has or has had seven young athletes living under her roof, including three — Cal, Jude and Anabelle Schembra — currently playing high school sports at Center Grove. A multi-sport athlete at Franklin Central in the 1990s who went on to play women’s volleyball at the University of Indianapolis and helped coach Roncalli to a 2006 state championship in that sport, Owen has seen travel sports become a more central part of the equation over the years, and she’s seen those expectations rise along with the money and time commitments.

One of the biggest problems, Owen says, is that too many parents get caught up throwing money in the wrong direction. She notes that her son Cal, a senior on Center Grove’s baseball team, used to play for the elite Indiana Bulls travel team before switching to Bargersville-based Top Tier Baseball, where he could make better use of the nearby training facilities and get more bang for his buck. It wasn’t the trendy choice, but it was what worked best for him.

“It’s like, ‘What does my kid really need?’” Owen said. “What is it? And if you’re paying $3,000 a summer just for a team, and then all of a sudden they’re sitting their butt on the bench and they’re not getting to play because you’re like, ‘Well, I thought this was the best team’ — it doesn’t matter what the best team is, or if they win a national championship at 13 years old. No one cares. I think everyone gets caught up in that. …

“I think so many parents are afraid to do what’s right for their kid instead of getting sucked up into what everyone else is doing. … It’s not a specific fault of their own; they just don’t know.”

More and more athletes are opting to hone in on one sport by the time they reach high school, especially at larger schools where there’s greater competition for roster spots and playing time. The multi-sport athlete isn’t completely dead, though; all three of Waalkens’ children have a different primary sport (baseball for 16-year-old Carter, soccer for 14-year-old Kinley and basketball for 12-year-old Kalle) that they play at a club level, but each still participates in more than one school sport and hasn’t felt pressure from coaches or friends to specialize.

“As parents, I worry about them doing too much and getting hurt, and then not being able to do something,” Renna Waalkens said, “but they haven’t felt that pressure from their coaches, their teammates, their travel coaches, anything. So I guess we found the right people and the right organizations.”

Chris and Aimee Alyea have always encouraged their kids to try different sports, but they understand that focusing on one has become the way of the world, especially for people with designs on competing in college and perhaps beyond.

“I think that sports are headed that direction or are in that direction already, so if you don’t do AAU or you don’t play year round, your skill level will not be at that full level as some of the other kids that are wanting to play in college,” Aimee Alyea said. “I don’t know if it’s really about scholarships as wanting to play beyond high school at the highest level possible. If our kids wanted to play at the highest level possible beyond high school, then I feel like skill-wise, it’s almost necessary to play year round.”

Doing so, though, does not guarantee a scholarship, stardom or even a spot in a high school starting lineup.

Owen, for one, feels that many parents get sold a false bill of goods by travel programs and want to believe it because it sounds good. Not everyone, she says, can be a superstar.

“The biggest piece that you can offer people is honesty, and I think unfortunately, in the world of travel sports, parents have a false idea now of what the reality is for their kids,” she said. “There’s some sense of reality that the world of travel sports has made people lose. It seems that people just don’t have a realistic view of where life is and where their kid is, and they can’t be okay with it. Like our daughter Malia (a former Center Grove volleyball player) … she did fine, but she was not great by any means, and I’m fine with that. I would tell her that — be the best version of yourself. You have a role; own the role and play it. And that’s okay. I think people, they feel ‘less than’ if their kid isn’t That Guy or That Girl. There’s nothing to be disappointed about. It’s okay.”

Owen’s hope is that more parents are willing to make the choices that are the best fit for their kids individually and not just throw money toward programs that are considered more prestigious just because that’s where everyone else is going.

“Your butt’s going to sit the bench; why would you want that?” she said. “You want to go and get better. Pick the right place for you, not the right place that everybody wants to just post, ‘I’m going here.’ And if that’s what’s right for you, then that’s fine — but do it for the right reasons. … It’s hard to figure that out, but if you can, then I think you end up really happy with that end result.”

And in the end, happiness should be the number one goal here anyway.

“The money that we invest is because they’re investing effort,” Aimee Alyea said. “If they love what they’re doing, and they’re putting 100% in, then we’re behind them.”