Less than four minutes into a phone interview earlier this week, Max Clark had to briefly excuse himself and mute the call.

“They just asked for my autograph at this Starbucks,” he explained a few seconds later. “I’m so sorry.”

A lot of things in Max Clark’s life have changed over the last year and a half, but not everything. Even back at home in Franklin — where you might think the novelty has worn off by now — he can’t go get a coffee without getting the star treatment.

Such is life as one of the hottest young commodities in the baseball world.

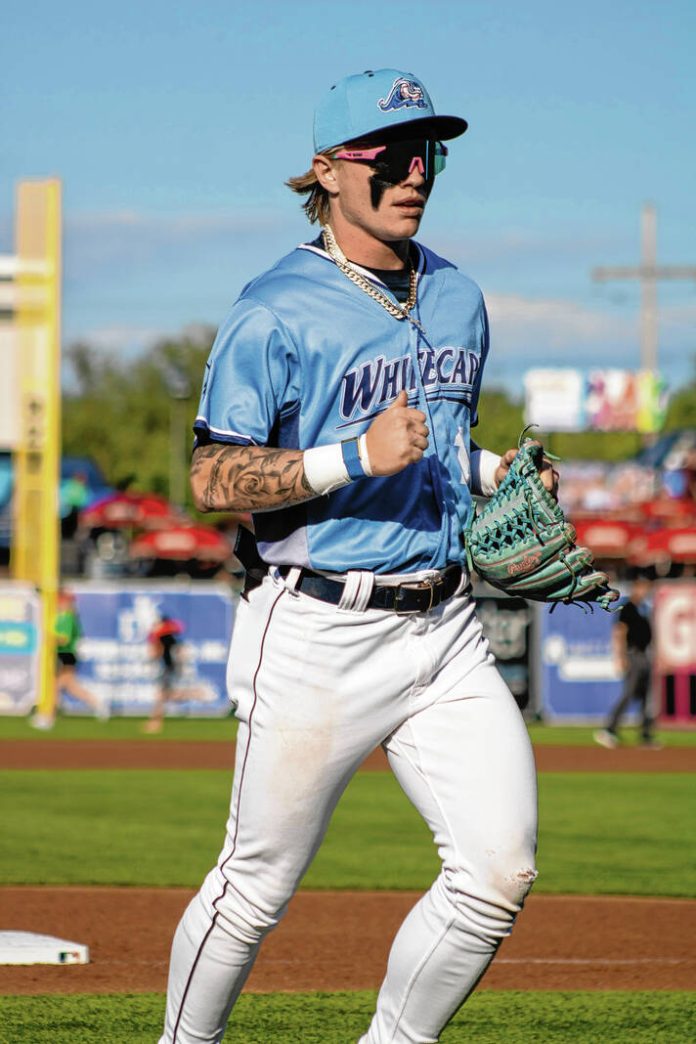

Clark is used to that part; he’s been signing autographs since he was a Grizzly Cub underclassman. His first full season as a professional, however, took him through plenty of new territory. It also brought him back from Florida to the Midwest, as he earned a late July promotion from the Low-A Lakeland (Florida) Flying Tigers to the West Michigan Whitecaps, the Detroit Tigers’ High-A affiliate just outside of Grand Rapids.

Being back within driving distance of his hometown for the last month and a half of his season made life much more enjoyable, since his family and friends were able to show up far more frequently.

“It’s definitely added a new level of excitement for the family and for local friends,” said Angela Ankney, Clark’s mother. “Lots of local people have made road trips, and it’s been fun to enjoy the game together with some families that we hadn’t seen … so that’s definitely been great.”

Just over his 34 games with the Whitecaps, Clark had the chance to play a road series in Fort Wayne, a little more than two hours away from home, and in Dayton, Ohio — which is a similar driving distance but also happens to be where his fiancée, Center Grove grad Kayli Farmer, is attending college and playing soccer for the University of Dayton. Even the Whitecaps’ home field, LMCU Ballpark, is a driveable four and a half hours away, and several locals made that trip at least once.

Clark noticed and appreciated the difference after largely being on an island in Florida for his first few months as a pro.

“That’s the name of the game,” he said. “When you’re going through these things and trying to become a big leaguer, the first thing that you want is your support group right by you — because this thing’s a grind, man.”

Working overtime

A grind, indeed. Clark played in 107 games this year, by far the most baseball he’s ever played in his life. The minor league schedule, with six-game series and an off day on Sunday, takes some adjusting to — but overall, Clark was pleased with how well his body handled it.

“The name of the game for us is get as far along in the season as you can before you start feeling run down and tired, and losing that feel for the game,” he said. “I was happy with how long it took me, especially my first year; it wasn’t until probably game 105 that I started feeling the full season come along. So each and every day we’re going to try and build that up for next year, and hopefully make it a couple of more games without feeling the way I did.”

The mental toll is equally heavy. With eight-hour days at the ballpark every time out and only one day off each week, minor leaguers are putting in overtime; by the time Sunday comes around, Clark said, all the players want to do is rest and recover to get ready for the week ahead.

Having others to go through that process with was critical, and Clark had good company all year. After rooming with fellow 2023 draftee Kevin McGonigle at the Tigers’ complex in Lakeland, Clark shared an apartment in Michigan with Joe Miller, a 24-year-old pitcher who had joined the Whitecaps in May but was also a teammate in Low A last season.

Clark says he’s enjoyed spending time with Miller, an Ivy League graduate (Penn) who shares his passion for talking about every aspect of the game. The two talked shop every night after games, just one of several things that Clark enjoyed about post-promotion life besides the upgrade in living space from the Lakeland dorms.

“I really loved the vibe in West Michigan, because I felt like it was the first time that it was true professional baseball,” he said. “You weren’t at the complex surrounded by all of the front office guys … you were legitimately on your own for the first time.”

Eyes on the ball

Of course, that promotion threw some chaos into what was already the busiest year of Clark’s baseball life — taking what was already a draining routine and throwing a 1,200-mile move in just for giggles. He suited up for the Flying Tigers on July 21 and was in the Whitecaps’ lineup two days later.

Through all of the upheaval, Clark had his hottest stretch of the season in July. Beginning with a 2-for-4 effort on the first of the month that included a home run, he batted .400 (16 for 40) with three homers, 12 RBIs and nine runs scored over his last 10 games with Lakeland. His final game in Low A saw Clark go 3 for 4 with a double, a home run, a stolen base and three runs scored.

During that run came a one-week hiatus for the MLB All-Star break, during which Clark played center field for the American League at the All-Star Futures Game in Arlington, Texas.

When the call came to head north, Clark was leading the Florida State League in RBIs with 58 and ranked second in runs scored (55) and steals (26).

Clark kept his heater going after his promotion, hitting safely in his first nine games with the Whitecaps while batting .405 (15 for 37) with three doubles and five runs batted in. He cooled off down the stretch, posting a .214 average from Aug. 3 onward, but he still finished with a .264 average in West Michigan — a decent number given the increased degree of difficulty. Clark says that the biggest difference between Low A and High A was the level of execution as he started dealing with more seasoned pitchers.

“You really have to pick your spots and when to be aggressive,” Clark said. “Like, this guy’s nibbling around the edge (of the strike zone) — that may be all I get this at-bat, so I have to do what I can do with it. You take what the game gives you a lot more at that level, because guys make way less mistakes. … This guy might leave a breaking ball over the middle in Low A and I wouldn’t swing at it, because I know he would eventually come back with the fastball because he couldn’t throw two or three breaking balls for a strike in a row. But guys in High A, they’ll throw you the breaking ball until you prove you can hit it. They’ll throw you the change-up until you prove that you can hit it. Or they won’t give you a heater in the heart of the zone; they’ll nibble around the edge and make you work for a single, make you work for a walk. There were no easy at-bats.”

Over the full year across both levels, Clark batted .279 with nine home runs, 75 runs batted in and 75 scored. He swiped 29 bases, hit six triples and posted a .372 on-base percentage.

Living up to the hype

Clark had plenty of buzz coming out of Franklin as the No. 3 overall pick in the 2023 MLB draft, and he hasn’t done anything to disappoint. He showed enough promise at both levels this season that former major league executive Jim Bowden ranked Clark second on his list of the top prospects in the game earlier this month.

“An on-base machine, Max Clark is an elite leadoff hitter who’s capable of stealing 30 to 40 bases per season,” Bowden wrote. “He has a great personality and eventually will be a fan favorite in Detroit. I absolutely love this player.”

No other prospect ranking has put Clark that high yet, but that may just be a matter of time. He’s currently sixth on MLB Pipeline’s list and looks primed to move up now that the top two (Junior Caminero and Dylan Crews) have been brought up to the majors. Clark was also ranked eighth by Keith Law of The Athletic in late July, but he looks likely to crack the top five on Law’s postseason list once current MLB players are removed.

When it comes to the prospect rankings, Clark says he’s “taking everything with a grain of salt,” pointing out that his job is to please the higher-ups in the Detroit organization and not anybody else. Still, there is a weight of expectations that most 19-year-olds don’t have to carry around with them all the time.

As similar as this journey might be to a teenager venturing far from home for college, it’s not entirely the same.

“The pressure to perform makes it a lot different,” Ankney said. “Under the microscope every single day with every single game.”

Larger than life

Every player in the minor leagues is being watched, but few draw as much attention as Clark. His status as one of the game’s top prospects alone puts a spotlight on him, and his massive personality only amplifies it. Clark has more than 425,000 followers on Instagram and another 340,000-plus on TikTok, and MLB Network had him wearing a microphone throughout his Futures Game appearance. He already has baseball cards — including a Bowman card that portrays him as a Garbage Pail Kid (“Max Elevation”) leaping to rob a hitter of a home run — selling for more than $500 on eBay, and he hasn’t even made it to Double-A ball yet.

Not surprisingly, he made an immediate imprint in West Michigan upon his arrival. Dan Hasty, who handles the Whitecaps’ radio broadcasts and doubles as a part of the team’s media relations staff, noticed it immediately.

“There was a lot more energy and electricity in the ballpark once we got him,” Hasty said. “Night and day. Our jersey sales spiked, our attendance went up. It was considerable and tangible to see those differences.”

The difference was big enough that West Michigan had a security detail assigned to him at the park — Ankney said that when she went up to games, she would either be escorted to her son after the final out or vice versa so that he could be protected from the crush of autograph-seeking fans.

Clark has always tried to be as accommodating as possible with his many supporters, but he’s had to learn how to strike a balance between pleasing the fans and fitting in with his teammates. After one game in Dayton, Ankney said she tried to point Clark toward a youngster who had come from Johnson County to see him — but he didn’t want to be seen as a prima donna by his peers after a tough loss that had eliminated the Whitecaps from the Midwest League playoff hunt.

Though he wants to give back to his fans — especially the kids — Clark has come to realize that there’s a time and a place to take care of that without upsetting team chemistry.

“You never want to upset anyone, you never want to come off as an arrogant diva, but you also have to understand what your teammates might perceive it as,” he said. “Because there’s a lot that goes into the game other than just the way you play. The one thing I learned this year as a professional was how important the clubhouse vibe is and how much that plays into how well your team plays. If the vibes in the clubhouse are bad and nobody’s having fun off the field, then it’s impossible to have fun on the field.”

Clark has had plenty of fun in 2024. He’s also grown as a player, earning a promotion and the respect of talent evaluators in the Tigers’ organization and beyond, and as a young adult who just spent an extended stretch of time away from home for the first time.

His mother was proud of how he handled it all.

“It’s been a learning year for him, because not only is it the baseball that you have to learn, but just being on your own, making decisions,” Ankney said. “Companies constantly after him for deals, you know, and he’s made good decisions. The decision making, the limit-setting, just time management and all of that … he’s just managed it really, really well.”

She wasn’t the only one; Clark certainly made an impression on Hasty over his brief time in Michigan.

“For being 19 years old, he gets it on a personality level unlike a lot of kids that I’ve seen at that age,” Hasty said. “Personally, I hope that he has a long major league career, because I would love to see him work at the MLB Network as an analyst. He has that kind of articulation and ability. And honestly, that might be selling him short, because he’s one of those guys that could do anything he wants to do after his playing career is over. He’s just one of those guys that will be successful no matter what.”

Which will only make it harder to make an anonymous coffee run, in Franklin or anywhere else.