As part of Franklin College Convocation Lecture Series, Richard L. Hasen, a lawyer and professor of political science at the University of California — Los Angeles and the director of the Safeguarding Democracy Project at UCLA School of Law, discussed voter rights Monday. Submitted by Chad Williams

Franklin College spotlighted voting rights in its annual Constitution Day lecture Monday.

Community members, staff and students gathered in the college’s Branigin Room to hear Richard L. Hasen, the Gary T. Schwartz Endowed Chair in Law and the director of the Safeguarding Democracy Project at UCLA School of Law, voter disenfranchisement over the years and how amending the U.S. Constitution could prevent disenfranchisement in the future.

Constitution Day was Sept. 17, but this year’s lecture topic transcends the day. By holding the lecture each year, the college hopes to promote civil discourse, which is “vital to a healthy democracy,” President Kerry Prather said. As they begin to participate in government and voting, students will be responsible for preserving the “self-government of, by and for the people,” he said.

“You are the next generation of leaders. Your presence here demonstrates your commitment to building civic awareness, which will empower you to help shape a more informed and engaged society as the timing of this program coincides with the national election,” Prather said.

Hasen’s presentation discussed barriers to voting that have impeded democracy in the past and still do so today. Part of the issue, he says, is that the Constitution does not contain an affirmative right to vote and the Supreme Court hasn’t upheld the right to vote for many citizens either.

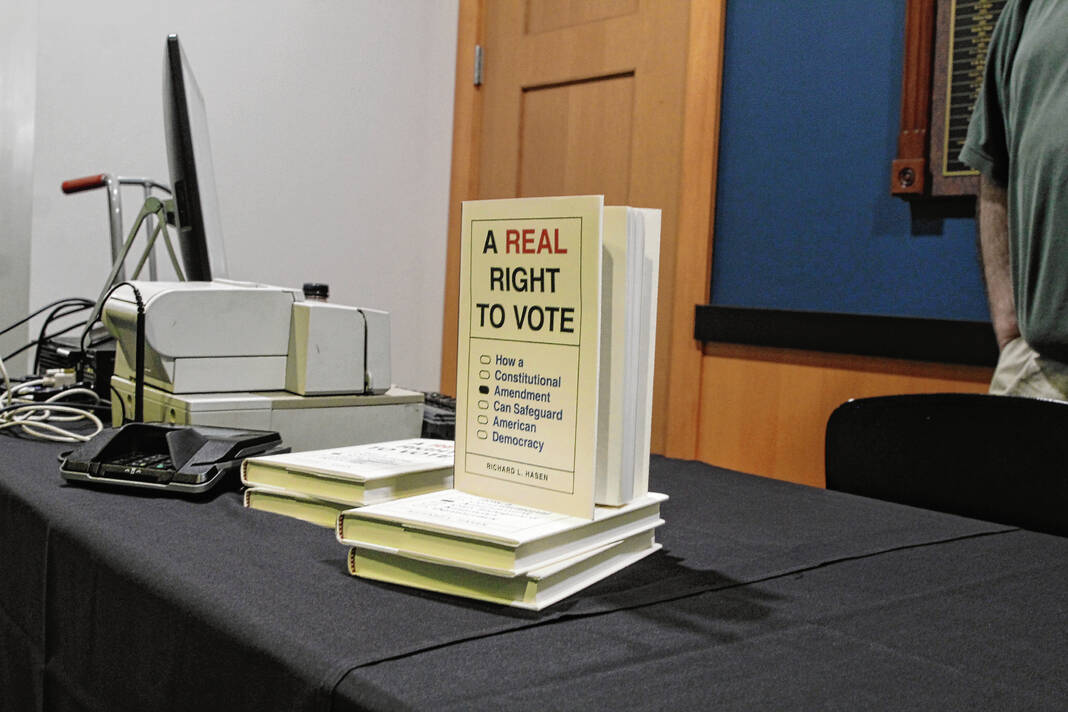

He believes voters should push for a constitutional amendment that would guarantee the right to vote for all and lays out a framework to get there.

Voting case law

There have been several U.S. Supreme Court cases that shaped the right to vote, Hasen said.

In 1872, Virginia Minor, a U.S. citizen and Missouri resident, was told she wasn’t allowed to vote because the Missouri Constitution only gave men the right to vote, according to Hasen. Minor took the issue to the Supreme Court and argued some amendments allowed her to vote, including the 15th Amendment. Justices ultimately decided that “voting is not a privilege of citizenship,” Hasen said.

In 1903, Jackson Giles, a Black U.S. citizen and resident of Alabama, was told he could not register to vote because of Alabama’s laws. He took the issue to the Supreme Court who ultimately said that was Alabama’s choice and there was nothing they could do.

It wasn’t until 1965 when Congress passed the Voting Rights Act that the right to vote was more firmly established in the Constitution. Even then, the Voting Rights Act doesn’t guarantee that everyone has the right to vote, Hasen said.

Military service members were also disenfranchised until the 1960s, Hasen said. Sgt. Herbert Carrington was told he couldn’t register to vote in a primary election in Texas because he was in the military, Hasen said.

When the issue was brought to the Supreme Court, Texas argued that military members were not residents and were passing through, which was not the case for Carrington. State officials also argued that allowing service members to vote could swap local votes and change the outcomes of elections, Hasen said.

“The Supreme Court’s response to that was, ‘Well, that’s the point of elections,’” Hasen said. “It’s a feature, not a bug, that if you allow people to vote, they might not agree with the other people who are voting and would get a different outcome.”

Most of the voting rights today come from an eight-year period when the court protected voting rights. That court dubbed the Warren Court, had a different view of how to read the Constitution than the current court does, Hasen said.

If the Carrington, Giles or Minor cases had come before the current court, Hasen thinks the outcomes may have been much different.

“There are signs from the current Supreme Court that these cases might not last,” Hasen said. “And so we might think that we have our voting rights protected, but in fact, a lot of it is shakier than we think.”

Major cases have gone through the courts as recently as 2000. That year, when the Supreme Court ended the dispute in Bush vs Gore, they told Americans that they “do not have in the Constitution the right to vote for president,” Hasen said. That decision is given to each state through their legislatures, he said.

“So for the next election, the state legislature could simply pass a law and say, ‘You know what, no more voting by the people for president. The Supreme Court said that’s just fine. That’s consistent with the Constitution,’” Hasen said. “That’s the problem with the Constitution.”

Disenfranchisement built-in

Having the right to vote in the Constitution will serve three purposes: promoting political equality, de-escalating the fight between political parties and making it harder to subvert election outcomes, Hasen said.

Elections in the U.S. are much different from other advanced democracies, Hasen said. In other countries like Canada and Germany, there is uniformity. Each ballot looks the same and each voting machine is the same, he said.

To make the system more fair, the government could register everyone eligible to vote and require them to have a national ID, Hasen said. That would eliminate about 70% of litigation in the country and deescalate fights over election rules, he said.

With each state deciding voting laws, the strength of voting rights depends on where a person lives and their socioeconomic status. Some socioeconomic classes face barriers when it comes to voting that others do not. One important case that determined voting rights was decided in Indiana in a case called Crawford v. Marion County Election Board. The Supreme Court upheld the law requiring voters to provide photographic identification despite the challenge that the law violated the Equal Protection Clause.

Some argued that Indiana’s strict voter identification law is a burden for many voters. For low-income voters who may be too poor to afford the documents required to get the free Indiana State ID, they have to go to their precinct after voting, at their own expense and sign an affidavit that says they are too poor to afford the documents, Hasen said.

Those who have a religious objection to being photographed and don’t have a photo ID also have to jump through the same hoops every single time they vote, he said.

Hasen argues that those rules should be changed if we want to “be a society of equals.”

In North Dakota, some indigenous people waited seven years for litigation to be resolved before they could vote. The state passed a law in 2013 that required voters to provide a residential street address. The law was passed after a candidate was able to win by about 3,000 votes in the 2012 election with the help of Native American voters, he said.

“So it looked like revenge,” Hasen said. “It took seven years of litigation until there was finally a settlement and the creation of new tribe lands, they had to actually create street addresses to allow people to vote, and in the meantime, it was a struggle. It shouldn’t be this way in a modern democracy.”

There is more election litigation today than before the 2000 presidential election. In 2020, the U.S. hit a record amount of election litigation, Hasen said.

This is in part because of the ever-changing rules. When the rules change, people sue, he said.

Even as recently as the 2020 election, legislators in certain states made efforts to change the electoral count of some states that President Joe Biden had won, Hasen said. This was an effort to change the outcome of the election to favor their candidate that was made possible because of the argument made in the 2000 Bush v. Gore case, he said.

This underscores the need for the amendment because election subversion would be “very difficult to do” if the Constitution contained an affirmative right to vote, Hasen said.

A potential solution

Because not everyone is guaranteed the right to vote, Hasen said citizens should encourage legislators to guarantee it with an amendment to the Constitution. Hasen’s amendment suggestion has six parts to it. Some, he acknowledged, would be harder to gain bipartisan support, but would be beneficial to democracy, he said.

First, all citizens, adults, residents and felons should have the right to vote for every office in their area, Hasen said. In 2022, an estimated 4.4 million people, or 2%, were ineligible to vote due to a felony conviction, according to the sentencingproject.org.

All votes should be weighed equally and the government should have universal voter registration, Hasen said. Many countries that run democracies have a similar system where everyone has a universal voter identification. That would eliminate concerns that people vote in two places, he said.

“If we didn’t have to spend all this time figuring out who’s registered to vote and purging the voter rolls and doing voter registration drives, we’d save a lot of money that could actually be spent on campaigns or on other things, and we get rid of all of that litigation over the registration rules,” Hasen said.

It should also be easier for voters to challenge burdensome rules, like Indiana’s voter identification law and North Dakota’s residential address law, Hasen said.

The U.S. should protect minority voting rights the way the Voting Rights Act of 1965 intended, Hasen said. The Supreme Court has been “whittling away at how it has been interpreting the Voting Rights Act,” creating disenfranchisement for minority voters, he said.

Lastly, Hasen says more power should be given to Congress to expand voting rights because the “courts record on voting rights have been so dismal.”

“If you look around the rest of the world, almost every other democracy runs their elections better than we do, and part of the reason for that is that we don’t affirmatively protect the right to vote,” Hasen said. “So if we really are serious about our democracy, we need to take steps, not just to keep fighting about the voting rules in this county or that county, but to actually think about what it would mean if the United States had a real right to vote.”