A former local lawmaker who was convicted of federal campaign finance violations has authored a new book about his time in federal prison.

Brent Waltz, a former Indiana State Senator and Johnson County Council member, is also continuing to maintain his innocence and alleging his conviction was the result of political retaliation by federal prosecutors.

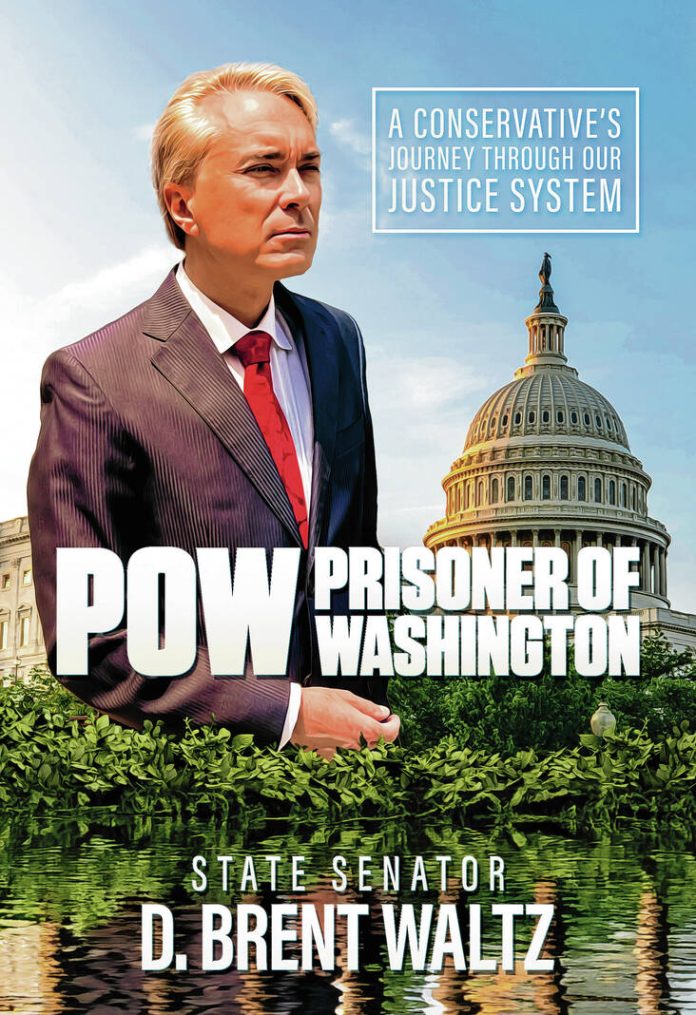

“POW — Prisoner of Washington: A Conservative’s Journey Through Our Justice System” was published Aug. 20 by Post Hill Press. The book aims “to expose the blatant targeting of various political figures; to provide an unflinching view of federal prison, which Waltz compares to living in an episode of ‘Hogan’s Heroes;’ and finally, to analyze the consistent political, societal, and economic corollaries found throughout U.S. history,” according to the publisher.

In the book, Waltz describes how the U.S. Department of Justice reportedly goes after political opponents and his experience being a reported target. Waltz also chronicles his life and experiences while serving 176 days at Federal Correctional Institution Ashland, a low-security facility with an adjacent minimum-security satellite camp in Kentucky.

Waltz decided to write “POW” for two reasons. The first is to share his side of the story since he wasn’t able to while the case was being adjudicated.

“The normal thing that an attorney tells their client is not to speak the media; don’t speak to friends or family about what’s going on,” Waltz told the Daily Journal. “When a person chooses not to do that under advice of counsel, you create a situation where only one side — in this case, the government — is doing the talking. And of course, the government knows this and uses that to their benefit in many, many cases.”

The other reason Waltz is sharing his story is because he says it is “important for citizens to know just exactly what their government and the tactics that they employ in the justice system to try to get results that they think would be appropriate,” he said.

“And in truth, [it] winds up being a significant perversion of justice,” he added.

Case background

Waltz and John S. Keeler, a 72-year-old New Centaur gaming executive and former Indiana State Representative, were indicted in September 2020 on charges of violating federal campaign finance laws, false statements and falsification of records, making illegal corporate contributions, and conduit contributions to Waltz’s unsuccessful 2016 congressional campaign. Waltz, a long-time Johnson County resident, served on the Johnson County Council from 2000 to 2004 and represented District 36 in the Indiana State Senate from 2004 to 2016. He left to run for U.S. Congress in the Ninth District but was defeated in the 2020 Republican primary by Rep. Trey Hollingsworth.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office says the plan was to transfer thousands of dollars from the accounts of New Centaur to Kelley Rogers, a Maryland-based political consultant, who would then contribute that money to Waltz’s 2016 congressional campaign. Rogers allegedly created fake invoices and agreements to make it appear like he was providing services for New Centaur, and recruited straw donors to each contribute $2,700 to Waltz’s campaign, the federal maximum contribution limit at the time, the indictment says. Straw donors are people who contribute to a campaign in their name despite receiving advance payment or reimbursement of all or part of the contribution.

A total of 15 straw donors were involved, including three of Waltz’s relatives and one of his business associates. The straw donors were reimbursed by Rogers using money from New Centaur. He also transferred money from New Centaur to Waltz, who also allegedly recruited straw donors and either reimbursed them or paid them in advance, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

New Centaur transferred a total of $79,500 to entities controlled by Rogers for the scheme, according to the indictment, but Rogers allegedly kept $33,300 of that to pay for his consulting fees for his services to Waltz’s campaign. Waltz also donated $10,800 of his own money to the campaign through straw donors, according to the indictment.

Waltz pled guilty in August 2022 to felony counts of making and receiving conduit contributions and making false statements to the FBI. In August 2023, Waltz tried to have his sentence overturned, claiming he had an ineffective lawyer during negotiations with federal prosecutors in 2022. He also said he pled guilty to two felonies without knowing that the specifics of the agreement made it more likely he’d serve prison time. The appeal is still pending.

Waltz felt targeted

Both in interviews and in “POW,” Waltz said he was targeted by federal prosecutors who hoped he’d assist them in indicting Rod Radcliffe, a longtime friend and wealthy supporter and fundraiser for former President Donald Trump. He alleges that when he refused to assist them, prosecutors turned their attention toward him, resulting in a 10 month sentence for a campaign finance violation.

To date, Radcliffe has not been indicted or formally accused of wrongdoing by federal prosecutors.

It was in 2016, during Trump’s first Republican campaign, when Waltz first received a phone call from the FBI, who wanted to meet with him. Waltz says this had nothing to do with him or his 2016 Congressional campaign, but rather agents asked him about Radcliffe and whether he did anything illegal. Waltz told them no and the agents left him alone for a time.

Around 2020, when Trump began his campaign for reelection, Waltz had another conversation with the FBI. In the intervening years, Waltz says agents looked at Radcliffe, Keeler and associates, going through financial records and business records as part of their investigation. They also looked at Waltz’s campaign finance records, he said.

During their investigation, the FBI found out Keeler had signed off on a professional service agreement with Rogers, which Waltz said he had nothing to do with. Prosecutors alleged the money received by Rogers through this agreement was a political contribution, rather than a professional services agreement and that professional service agreements are deductible against the income of a company and political contributions are not. Waltz says this resulted in an additional federal tax liability of $14,000 — above the $10,000 statutory threshold for felony tax evasion.

Waltz maintains he wasn’t involved with this.

“It’s those kinds of things that I think should make citizens question exactly what the government is doing to their citizens — particularly those that happen to be conservative, Republican and supporters of Donald Trump,” he said.

What’s in the book

In the book, Waltz also describes the day of his arrest, his time in prison and what he observed.

“The 176 days that I spent in captivity would not be what most people would consider to be a federal prison,” he said.

Waltz described FCI Ashland as a “prison camp” where inmates were free to move around and had jobs working at the camp. There were no criminals convicted of a violent crime either, he said.

But still, he was away from family and friends, which was challenging, he said.

At one point in the book, Waltz describes how his fellow inmates named him “shot caller.” He earned the title as he essentially “ran” things while incarcerated, with fellow inmates saying they had his back, he said.

He also describes witnessing blatant racism against Black inmates, rampant drug use and smuggling and being subjected to unsanitary medical procedures and unhygienic conditions while in custody.

The book also features an analysis of current events in a historical context of where America is as a society by Waltz, the book’s publisher says.

What’s next

Before all of these events occurred, Waltz said he was “getting a little lazy” and was no longer involved in politics. Instead, he was focused on his business interests.

But after being indicted, convicted and spending time in prison, Waltz is reinvigorated.

Since he got out, he’s again been focused on his business interests and he’s been traveling a great deal. Business is going very well, he said.

“Had this not happened to me, I think I would have been very content to be far lazier than I am today,” Waltz said. “The irony to this whole thing is, if the Department of Justice was hoping to have me go quietly into the night, or remove me from the chessboard of life, they’ve done just the opposite. They have instilled in me a drive and a purpose, which I had lost several years ago, but I’ve certainly found it again today.”

Waltz hopes future leaders will demand better oversight of the justice system, which he describes in the book. He also hopes citizens, whether from Johnson County and beyond, look at his side of the story, along with prosecutors, and draw their own conclusions about what happened.

“That’s what our system is supposed to do, and unfortunately, the justice system is designed to make it very difficult for that to occur, and that is unfortunate,” Waltz said. “We all lose when that happens, and unfortunately, it seems to be happening at an ever-increasing rate these days.”