I’m drifting into a dark place/trying to keep this part of my heart safe

My soul basically been shark bait …

— Tarik “Black Thought” Trotter

The human brain is still developing until we reach our mid- to late 20s.

A teenage mind is thus an unfinished project, a work in progress, and each one develops differently and responds to various stresses in different ways. But stress is a fact of life, and even the most resilient adolescents are going to go through tough times.

For young athletes, there are even more opportunities to get tripped up. Academic and social stresses are compounded by the time commitments and pressures that come with competing — especially in a year-round sport such as swimming that offers very few periods of down time to physically or mentally recharge.

“What was hard for me was there was no end to the season,” said former Center Grove swimmer Grace DeLuna, who scored at the high school state meet as a sophomore but walked away from the sport shortly thereafter. “A lot of other sports, you have school and you have club, but for swimming it’s all connected, so it really is hard to kind of separate yourself from what you’re doing and take needed breaks. Even going on vacation, I would be practicing, because that was just normal. It definitely is hard to not really have an offseason ever.”

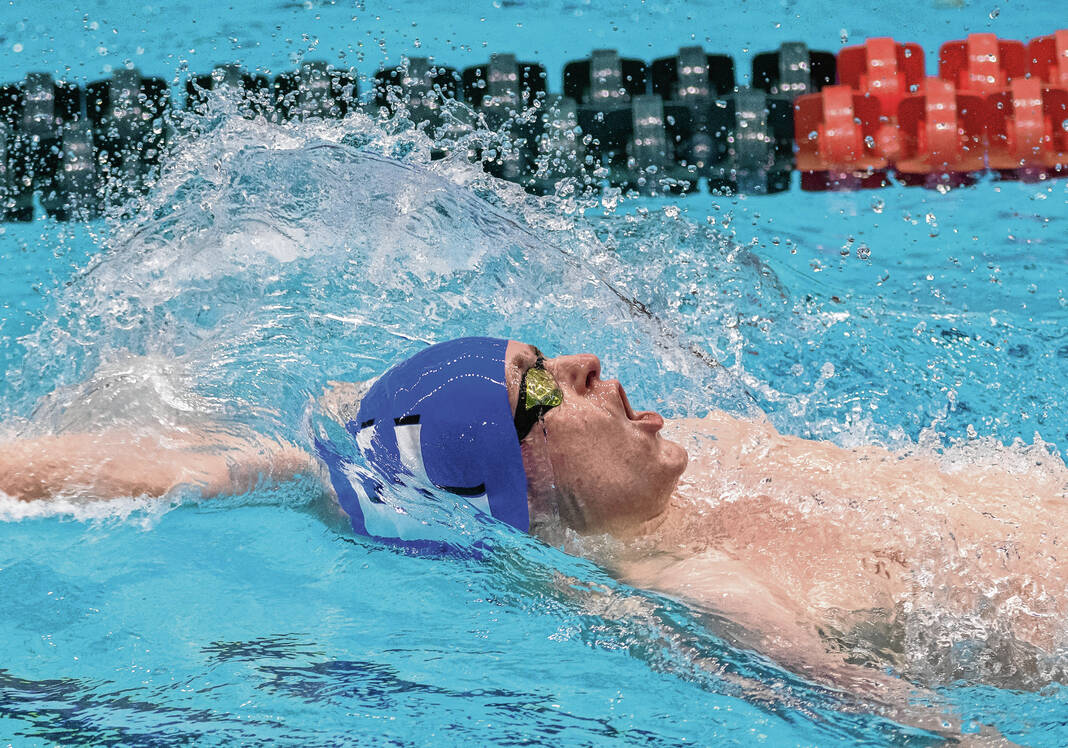

These months of December and January can be particularly grueling for a swimmer, especially at high school age. With practices often taking place both before and after school, many of them are going in when it’s dark outside and coming back out when it’s dark again. Athletes in other sports can run into similar walls. In those times when the workload is at its heaviest and there’s no instant gratification on the immediate horizon, even if the athletic part of the puzzle isn’t what breaks you, it can wear you down enough to make life’s other stresses too much to handle.

It ain’t all good

Cade Oliver swam for most of his life, and he was pretty damn good at it. He was a state runner-up in both the 200-yard individual medley and 100 backstroke as a Franklin senior in 2021, and he swam in the U.S. Olympic Team Trials that summer.

Stress was almost always there in some form, but it didn’t really start to register with him until his sophomore year of high school.

“As an age grouper, I didn’t really deal with a whole lot of mental health issues — or at least I didn’t think about it as much,” Oliver said. “But as you get older and you feel like you’re learning your emotions more, especially in high school, you learn that your emotions have a toll on you. … Having this constant months on end of, you’re not really doing very good, you’re getting beaten down, you’re getting beat down even worse. It’s like you’re getting kicked while you’re down, and as a high schooler you start to realize like, ‘Oh, this doesn’t feel good.’ And then you’re going through school, you’re going through relationships — and a lot of people say that it’s just high school, you’ll learn, you’ll get better, but high school’s where it really starts to tip you over that edge.”

For Oliver, though, high school was just the start. He’d never really wanted to go to college; school just wasn’t necessarily his thing. But his swimming talent earned him a scholarship opportunity at the University of Missouri, so he figured he might as well give it a shot.

Just as he expected, it wasn’t for him. Oliver was back home for good less than a year later. He’s in a good place now, currently working for the Edinburgh Fire & Rescue as well as Indianapolis EMS, but his road to today was littered with potholes. He calls college “a really deep, dark point in my life.”

Swimming wasn’t what made that year so dark for Oliver — he says if he could work as a firefighter and also compete as a college swimmer, he’d probably do it — but the stresses of being in a Division I sport did probably exacerbate any surrounding problems. The anxiety that came with taking on so many new experiences was heightened by not having a more familiar support system around him. At Missouri, there wasn’t enough time to build the same deep relationships he’d built with his coaches — especially Franklin head coach Zach DeWitt — here at home.

“It’s different in college, because I don’t know those coaches as well as I knew Zach,” Oliver said. “He was someone that really was able to understand me and able to keep in the sport through thick and thin. We had our arguments … and we had times where we were crying together. We had all sorts of ranges where we were laughing, crying, yelling, screaming sometimes, but he was able to keep me in the sport. And knowing that you have someone that loves you enough to keep you in something that maybe you don’t necessarily love — it’s all about people. In my opinion, if I hadn’t had someone like a Zach or (former Franklin assistant and current Purdue head coach Alex) Jerden in this sport, I don’t think I would have stayed in it as long as I did. That’s what kept me going through high school, and leaving high school, just realizing I didn’t have those people anymore, really threw me over the edge.”

Center Grove coach Brad Smith, who’s been mentoring young swimmers in Johnson County for more than three decades, has seen his share of swimmers go through mental health struggles for a myriad of reasons. He’s also endured his own, losing his son Chase to cancer in 2021 after a seven-year fight.

His personal experiences have helped make him more aware of whatever his swimmers might be going through in their lives.

“Everybody has their problems,” Smith said, “and I’m not going to say, ‘Well, at least your son didn’t die.’ Everybody is going through something. It may be finals, it may be parents are getting a divorce, it may be cancer. But whatever the case is, that’s what’s on their plate, that’s what’s in front of you. And so going through that has definitely made me more sensitive and more aware of what everyone else is going through.”

Feeling betrayed

Sometimes, the forces that tip a teenage athlete over the top do come from within the sport.

The pressure to perform at a high level, whether that comes from family, coaches, teammates or within — is very real. College scholarships are at stake, and those can make or break a young person’s future beyond athletics.

Additionally, there’s the validation that comes with being a valued member of a team, and even just losing that can be too much to bear.

One area swim parent, who requested anonymity because her child is still going through intensive therapy after being diagnosed with adjustment disorder, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, points out that young athletes rely on their coaches to look out for them and have their backs — and when those people fail them or betray them, it can leave some lasting scars.

Her child, she says, was emotionally abused by a former club coach as a 10-and-under swimmer and then kicked off of a high school team as a senior last winter. The combination of those traumas, she believes, sent her child into a downward spiral that wound up requiring hospitalization this year.

“These adults do not understand how they are affecting children,” the mother said, “and the parents of these children are entrusting — and in my case, paying — for these adults to have my (child)’s best interests at heart. And they failed.”

Not all such failures are malicious and intentional; DeWitt says that coaching can sometimes turn into a battle for a kid’s soul, and he admits he hasn’t been able to win them all. But he has always tried to, and over the years he’s come to realize that the most important part of the battle can simultaneously be the simplest and the most difficult.

“We’re very quick to direct things, both verbally and physically, and I think sometimes we’ve got to be the best listeners in the room,” DeWitt said. “And that’s something that we all struggle with, myself included. Because coaching really is a partnership with your athletes, and I’ve found that the bus goes further when I’m not driving it. I need to be the navigator, but I don’t need to be the one turning the wheel and pressing the gas. It needs to be them.”

Smith, too, has made more of an effort to listen to his swimmers when things aren’t going well.

“I ask my kids to have open communication about it all,” he said. “Sometimes what we think are issues never faze them, and then the littlest things are the biggest issues to them. So as a coach, I think that communication’s the key to helping them.”

Switching lanes

DeLuna was a high-level swimmer through much of her childhood, an Age Group State qualifier from 10 years old on. But accompanying her talent and accomplishments was a desire and a pressure to keep achieving more, and that led to some serious anxiety during meets — even at a young age.

“I remember when I was, I think I was probably 12, at state going into finals,” DeLuna recalled. “Berit Berglund, who’s an amazing Carmel swimmer, we were right there next to each other for the 100 back, going for the state record, and I don’t think I’ve still ever been more stressed out than I was in between mornings and finals. And so that was my first instance I can remember of such bad meet anxiety, and then it just got more and more.”

Further complicating matters was a nerve injury that DeLuna suffered when she was in eighth grade. The injury required surgery and limited her ability to practice, and while she remained a state-level swimmer afterward, DeLuna’s confidence in the water was never quite the same.

As she got into high school, she started to channel more of her energy into show choir and theater and found that she had a real love for performing. As that love grew, her love for competing in the water began to fade away.

“When I was in middle school, I was super fulfilled with swimming, and that’s all that I wanted to do,” DeLuna said. “And then when I was in high school, I felt that way about performing, and then it kind of came down to, ‘Well, after college I can perform; after college … a lot of people just don’t swim anymore.’ So it just made more sense. I was more fulfilled, and I just felt like it was something that I should commit to, because it made me feel like how swimming was when I was younger.”

DeLuna balanced the rigors of both singing and swimming through the first half of high school and continued to have success. As a Trojan sophomore, she reached the consolation final of the 100 backstroke at the state meet, and she kept going into the long course season that summer with Center Grove Aquatic Club. Late in the summer season, though, DeLuna aggravated the nerve injury in her back and found out she wasn’t going to be able to swim at the Senior State or USA Swimming Futures championship meets.

Not really being upset by that news, she says, was her cue to step away for good.

“I almost felt relieved a little bit,” said DeLuna, who is now studying vocal performance at the Chicago College of Performing Arts. “Because I was so tired that I was like, ‘It will be nice to be able to actually go to my first day of school and not be in North Carolina or Wisconsin for a swim meet.’ It’s weird how not sad I was, because a lot of people, being told they wouldn’t be able to swim at those meets, that would be heartbreaking. It just wasn’t as upsetting, because … I was just so tired.”

She still loves swimming; DeLuna teaches lessons and enjoys going to open swim times and just being alone with her thoughts in the water. Grinding her way through practices and dealing with the overwhelming meet anxiety, though? Not so much.

“It just felt like, when I was at swim practice, the way that I felt, I didn’t know if I could do that for six more years,” she said. “Honestly, that was the biggest thing. I was so stressed all the time. I was overworking myself, and it just felt like realistically, I had to sit down and ask myself, ‘Can I do this?’ And I felt like the answer was no.”

Beneath the surface

While the big stresses that Smith mentioned — family issues, schoolwork, social relationships — are big contributors, those have always been around in some form. But more and more young athletes have been struggling mentally in recent years, or at least more likely to make those struggles known.

It helps that high-profile athletes such as peerless gymnast Simone Biles, tennis star Naomi Osaka and swimming legend Michael Phelps have openly spoken about their own issues; that has empowered more young athletes to speak out when they’re feeling that anxiety or depression themselves. Franklin’s swimmers have been wearing green ribbon decals during some meets this season — girls on their faces, boys on their chests — in support of mental health awareness. We’re no longer living in an age where such feelings are seen as signs of weakness and thus kept bottled up.

But the rise in mental health cases isn’t solely attributable to a rise in athletes coming forward. There’s also been an uptick in overall quantity. Other general societal changes are lurking as low-key contributors, especially since the onset of the pandemic more than three and a half years ago.

The shutdowns that ate up much of 2020 and spilled over in at least some capacity into 2021 definitely made an impact on teenagers’ overall well-being.

“These adolescents had everything taken from them,” the unnamed swim parent said. “Whether it’s band, choir, swimming, theater, it was gone, and so for a lot of these kids, there’s schoolwork and then there’s extracurriculars, and a lot of these kids depend on the extracurriculars to get them through their academic day.”

COVID, DeWitt says, also helped accelerate a trend away from interpersonal relationships that had already been building up steam as people have become more reliant on automation and social media.

“It’s so much bigger than just the school part,” he said. “When we were kids, we went in a gas station and paid for our gas and we had to talk to an attendant. If I wanted to go eat at a restaurant, I had to go up to somebody and order; I couldn’t just order online. … We were brought up in an era where we were forced to interact with people that we didn’t want to interact with, and I think for the most part what COVID did is it enabled an already increasing thing made possible by technology — which is to say that we don’t have to deal with one another anymore. …

“For kids, it’s made them more isolated than ever before.”

Talking it out

Those feelings of isolation can lead teenagers to believe that nobody understands what they’re going through, pushing them to keep their problems to themselves.

But that, Oliver says, isn’t the answer. He started talking with a therapist as early as his sophomore year of high school and remains a full-throated advocate for finding someone to talk to about your problems.

“Therapists are great people,” he said. “They deal with a lot, and they truly are just there to listen, and I think that’s what a lot of people need. A lot of kids, especially, may not have the best life at home or might not have necessarily the best friends, and so they just need someone to listen to them. Even if it’s just someone that they’re paying to listen to them, it’s someone that can not necessarily offer them the solution to their problem, but offer them an outlet for their problem.”

“Personally, I couldn’t encourage it more,” Smith agreed. “Going through our journey (with Chase’s cancer), all four of us in our family went through counseling and therapy. … The importance of that, to have a sounding board, I just think it’s so important to have that in place. And sometimes it may be a professional therapist or counselor, and sometimes it may be just that weekly visit with a friend type thing. We’ve got kids that see weekly therapy, and I treat that just as important as (if) they are going to the doctor because they’re sick. They need that to get better and to heal whatever is going on.”

More and more, mental health issues are indeed being viewed in the same way as physical injuries; most major Division I colleges employ sport psychologists to ensure the mental well-being of their athletes. Such resources aren’t yet readily available at most public high schools, but thanks to the increased spotlight on mental health, perhaps that isn’t too far off in the future.

“It’s not just swimming,” Oliver said. “It’s all other sports. You’ve got your days where you’re high, you’re feeling good and you’re on top of the world, and then the next day you come in and you’re at the lowest point of your life. It’s a constant up and down, and as high schoolers and as littler kids, you don’t really know how to handle it, so there’s a lot of learning how to cope with it through parents, through coaches, through whoever.

“I do think that coaches are definitely becoming more aware of how to handle it, but it’s a learning process for everyone. There’s a lot of learning how to cope with not just swimming bad or doing bad in a sport, but also coping with doing bad in school or doing good in school. Learning how to go around things, make things better, figuring out what to do.”

And understanding that no matter what your problem is, you’re not alone.