Local fire departments are taking part in an initiative to get rid of firefighting foam containing toxic chemicals.

Recent research shows that one of the tools firefighters used for extinguishing blazes for years is also a main source of cancer-causing chemicals. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, is a large group of toxic chemicals used in thousands of consumer products — including foams used to fight fires.

The Indiana Class B PFAS Foam Collection Initiative is looking to tackle this problem head-on. With a focus on protecting firefighter safety, state officials will remove and properly dispose of PFAS material from any agency that requests it, for free. The program is a collaboration between the Indiana Department of Homeland Security, or IDHS, and the Indiana Department of Environmental Management, or IDEM.

“The new collection and disposal program allows Indiana to protect Hoosier firefighters and the environment. Minimizing exposure to Class B firefighting foam will have a big impact on the health of firefighters across Indiana,” IDHS officials say.

The creation of the program follows the passage of House Enrolled Act 1189 in 2020, which prohibited the use of firefighting foam containing PFAS for training purposes. An exception does exist for testing facilities that have implemented “appropriate measures” to prevent releases to the environment, officials say.

Gov. Eric Holcomb also included PFAS foam disposal in his 2022 Next Level agenda, including $1.5 million in initial funding for the initiative, according to news reports.

Since the program was established earlier this year, officials have been able to collect nearly 19,000 gallons of firefighting foam containing PFAS chemicals from 133 fire departments. Another 39 departments have collections pending, eight have collections scheduled and another 10 have been contacted by officials, according to IDHS.

The state agency contacted fire departments to determine if they have PFAS-containing foam on hand. The four Johnson County fire departments that reported having the foam on hand — Edinburgh, Greenwood, Needham and White River Township — have already had their foam collected.

The Greenwood Fire Department had used a firefighting foam containing PFAS for the last 30 years for both active fires and training, said Brady Coy, assistant fire chief. The aqueous film forming foam, or AFFF, is used to put out oil fires such as those from cars or airplanes.

The department limited the use of the foam after the state adopted legislation restricting its use, and after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency classified some of its ingredients as dangerous and harmful due to PFAS, Coy said.

“We could still use it on active scenes, but we couldn’t train with it,” Coy said. “We kept it in service for extreme cases.”

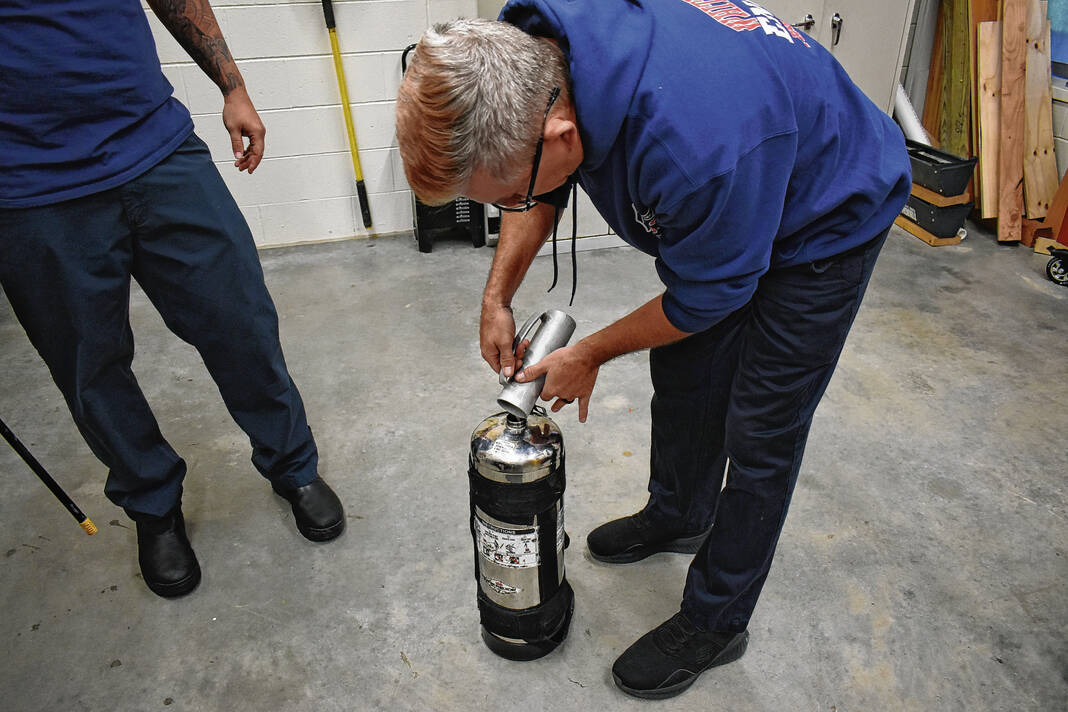

Greenwood Fire had 48, five gallons buckets of the PFAS firefighting foam that state officials picked up and disposed of in May as part of the program, Coy said.

White River Township Fire Department hasn’t used PFAS-containing foam in about 15 years, but had 50 gallons picked up as part of the state program in May, said Jeremy Pell, fire chief.

When firefighting foam containing the chemicals is used to put out a fire, the byproducts seep into the ground and stay there. It also can flow into drainage systems and eventually waterways, he said.

The White River Township firefighters steered away from the PFAS-containing foam after officials discovered Cold Fire, a foam product officials say is safe and better at extinguishing fires. That foam is more environmentally friendly and can be used for oil and gas fires, Pell said.

Chemicals linked to health problems

Most people in the U.S. have been exposed to PFAS and have the chemicals present in their blood, and the chemicals have been linked to a variety of health concerns, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Once they get in the environment and they get into our bodies, they don’t break down. That’s why they’re harmful,” Coy said.

Because they don’t break down, PFAS chemicals have been given the name “forever chemicals.”

Research has suggested that high levels of certain PFAS chemicals may lead to increased cholesterol levels, changes in liver enzymes, increased risk of high blood pressure or preeclampsia in pregnant women and increased risk of kidney or testicular cancer. Other possible health effects include changes in liver enzymes, small decreases in infant birth weights and decreased vaccine response in children, according to the CDC.

Hundreds of everyday products are made with highly toxic PFAS chemicals, including nonstick cookware, water-repellent clothing, stain-resistant carpets, furniture, food packages, personal care products and cleaning products. However, most exposure tends to be low for today’s consumer products, the CDC says.

There have also been numerous examples of the chemicals contaminating drinking water, waterways, soil and people across the country. In 2019, Kentucky officials found forever chemicals in the drinking water in the city of South Shore. The levels were at a higher concentration than anywhere else in Kentucky, according to news reports.

Indiana communities have also found PFAS in drinking water systems. IDEM released the final results of its first phase of water testing for the chemical in May. The agency found various PFAS chemicals in the raw water of 13 water systems and the treated water of 10 systems.

The chemicals were detected in the Edinburgh Water Utility’s raw water, but not in the treated water. The levels detected were not above the EPA’s health advisory levels to cause concern, according to IDEM.

Program offers benefits to firefighters, public

One of the top benefits of the program is how it improves the safety of both firefighters and citizens, Pell said. The initiative takes the chemical out of circulation to both the public and firefighters.

“It takes it out of circulation,” he said. “It’s one less chemical we are exposed to on the job.”

Another benefit of the initiative is that it’s free. White River Township Fire did not have to find money, people or resources to help get rid of the chemical — something that is more difficult than it sounds, Pell said.

“We’re in the business of handling 911 calls, not disposing of hazardous chemicals,” he said. “That should go to someone who has the expertise.”

Getting rid of the chemicals would have cost the departments a significant amount of money, local fire officials said.

“How do you take a large amount of the product and get rid of it? It costs a lot of money,” Coy said. “For the state to join with U.S. Ecology to help fire departments, that was the right way to go about doing that.”

Pell says the program is a model for how government should serve people. The government recognized the danger and recognized that local fire departments do not have the ability or resources to get rid of these chemicals on their own, so officials came up with a solution, he said.

“It’s the model way to identify a problem and create a real solution to help people,” Pell said.