A room in complete disrepair is seen during an inspection on Nov. 28 at the Red Carpet Inn and Fanta Suites in Greenwood. A Johnson County judge has ruled in the city of Greenwood's favor to forcibly vacate employees who were living in the hotel.

Photo provided by Johnson County Health Department

Employees who live at the Red Carpet Inn and Fanta Suites in Greenwood will have to vacate the property, a judge ruled Wednesday.

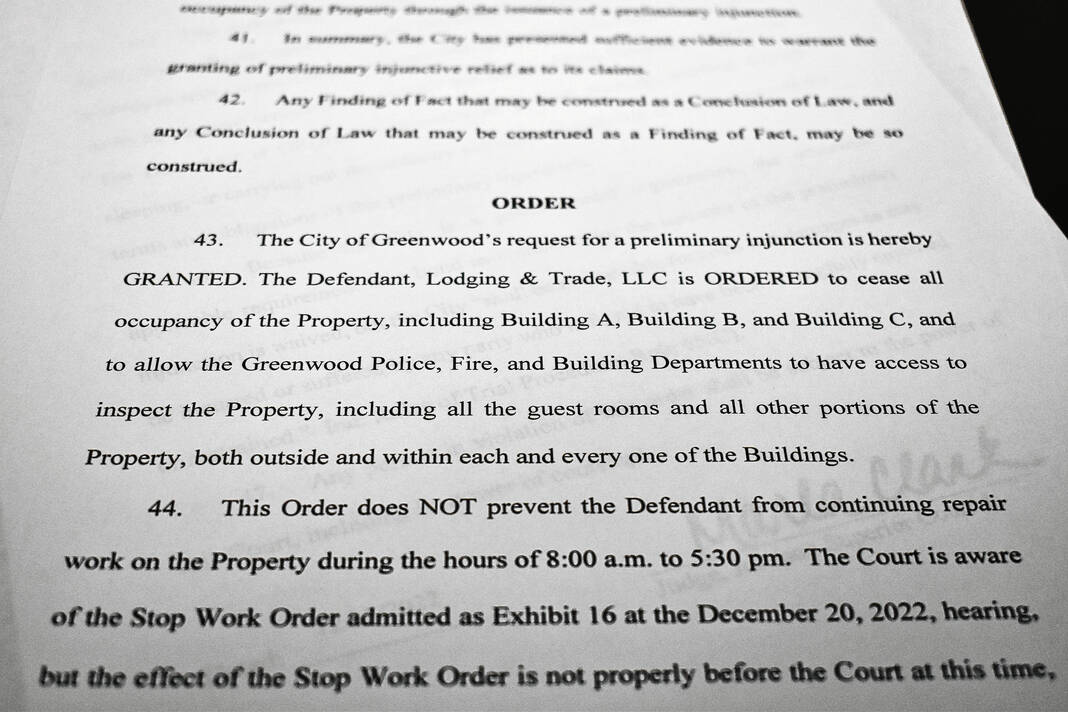

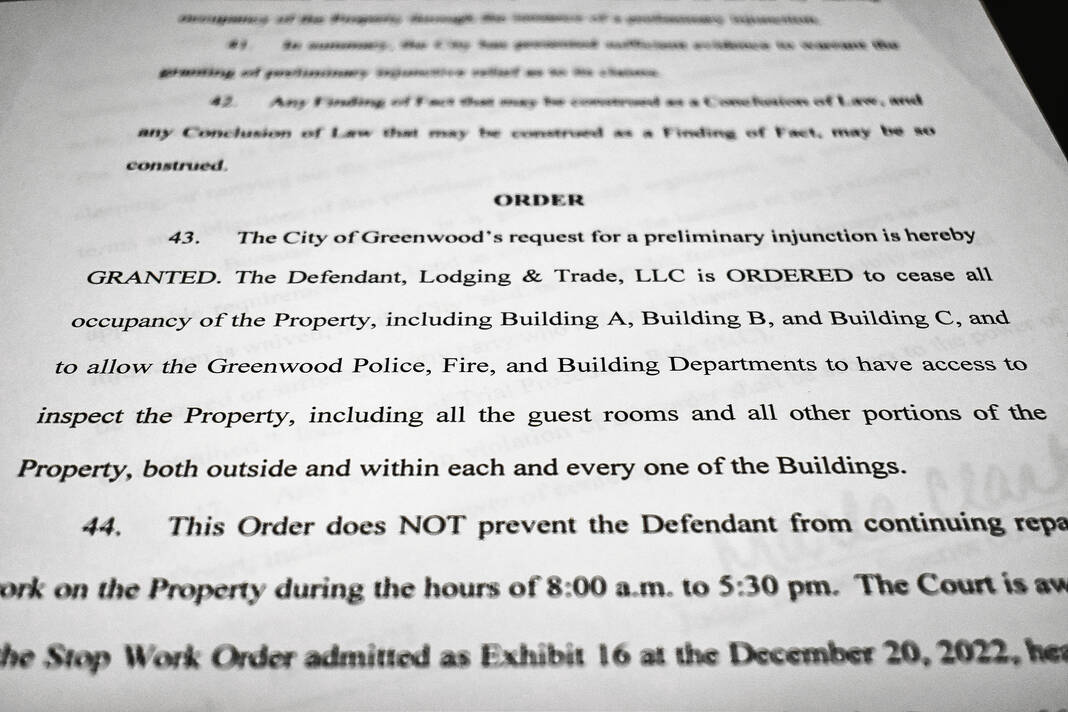

Johnson County Superior Court 4 Judge Marla Clark granted Greenwood officials’ request for a preliminary injunction to force employees who reside at the troubled hotel to vacate the property. Officials are suing the owners of the hotel, 1117 E. Main St., in civil court to force compliance with previous orders to vacate. Clark also ruled that the hotel’s owners allow city inspectors access to inspect the entire property, including both inside and outside the hotel’s three buildings.

The order does not prevent Ahmed Mubarak, the owner of the hotel, from continuing repair work on the property between the hours of 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday, as set in a previous agreement, the order says.

Any person in violation of the order is subject to the power of the court, including the possibility of contempt charges, the order shows. As of Thursday morning, city officials have not yet checked to see if the hotel is complying with the injunction, Building Commissioner Kenneth Seal said via email.

The order comes a little more than a week after city attorneys argued the hotel’s owner was violating a Greenwood Advisory Plan Commission order to vacate the property by allowing employees making repairs to the hotel to continue to occupy the hotel. The hotel’s attorneys argued Mubarak was justified in allowing the employees to continue to occupy the hotel as he need to have workers on the property who could make repairs.

Clark disagreed, saying this did not show evidence the hotel would be harmed by city officials’ moves to have the hotel forcibly vacated. The order says the city met all four criteria to grant the preliminary injunction.

During last week’s hearing, the hotel’s attorneys repeatedly argued that the city was making it “harder than necessary” for Mubarak and his employees to correct the conditions found in the hotel. A point of contention was the Oct. 24 agreement for the vacation of the property within 48 hours, which also limited the hours during which repairs could be made.

However, the limitation in hours was imposed by the plan commission, a city board, not the city itself. Additionally, Mubarak’s attorney at the time of the October agreement agreed to this limitation, Clark ruled in her order.

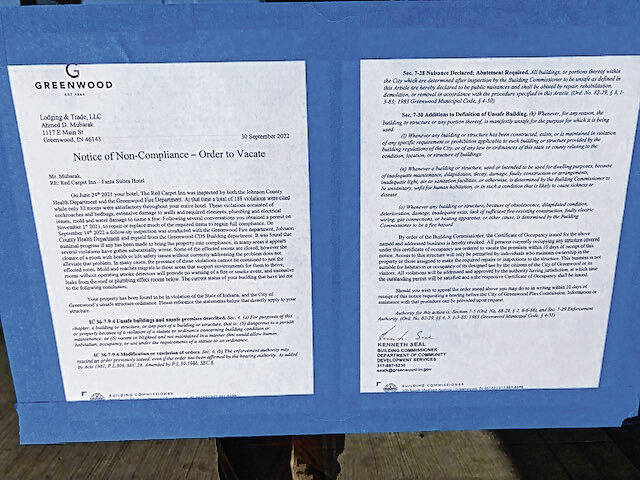

The commission later found the hotel was in “willful violation” of the September and October orders of noncompliance and notices to vacate.

The testimony and evidence the city presented conclusively show there was an explicit agreement that the hotel would be vacated by Oct. 26, according to the order. Testimony and evidence also showed people continued to live at the hotel in violation of the agreement.

“Further, these persons were not remediation workers as contemplated by the parties’ agreement, or if they were, they were residing as well as working on the property,” Clark concluded in her order.

Clark also ruled that the agreement does include inspection access to the hotel, and that Mubarak and the hotel refused “at least partial inspection access” on Nov. 28 and Dec. 20. In November, officials were granted access to only one of the hotel’s buildings, and a December inspection was refused by Mubarak, who told Seal to speak with his attorney.

The foundation of the city officials’ case was that the building was unsafe and that the health and safety of the public was paramount. Seal, Fire Marshal Tracy Rumble, Deputy Fire Marshal Ryan Angrick and Johnson County Health Department Director Betsy Swearingen all testified that the building was unsafe and shouldn’t be occupied.

“If occupancy itself is not only the breach, but also the unsafe danger, then the only remedy is a cessation of that occupancy,” Clark wrote in her order.

The evidence — which Clark notes is undisputed — shows that despite having 18 months to make repairs to remedy unsafe conditions, the hotel’s owners did not and allowed them to worsen. Given the totality of the circumstances, Clark found that the public interest would be served by barring occupancy through the injunction.

“The property presents serious health and safety issues in the city’s community,” Clark concluded.