Janet McDuffey, 81, is one of Booker T. Washington School’s last surviving alumni. McDuffey went to the all-Black school in Franklin from first to third grade around 1950.

ANDY BELL-BALTACI | DAILY JOURNAL

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series on Black history in Johnson County in celebration of Black History Month and the county’s bicentennial.

Her home on West Street is just a stone’s throw away from history.

Janet McDuffey, an 81-year-old Franklin resident, remembers attending the Booker T. Washington School around 1950. In her first, second and third grade years, it was the only Franklin school she was allowed to go to for one simple reason: she is Black.

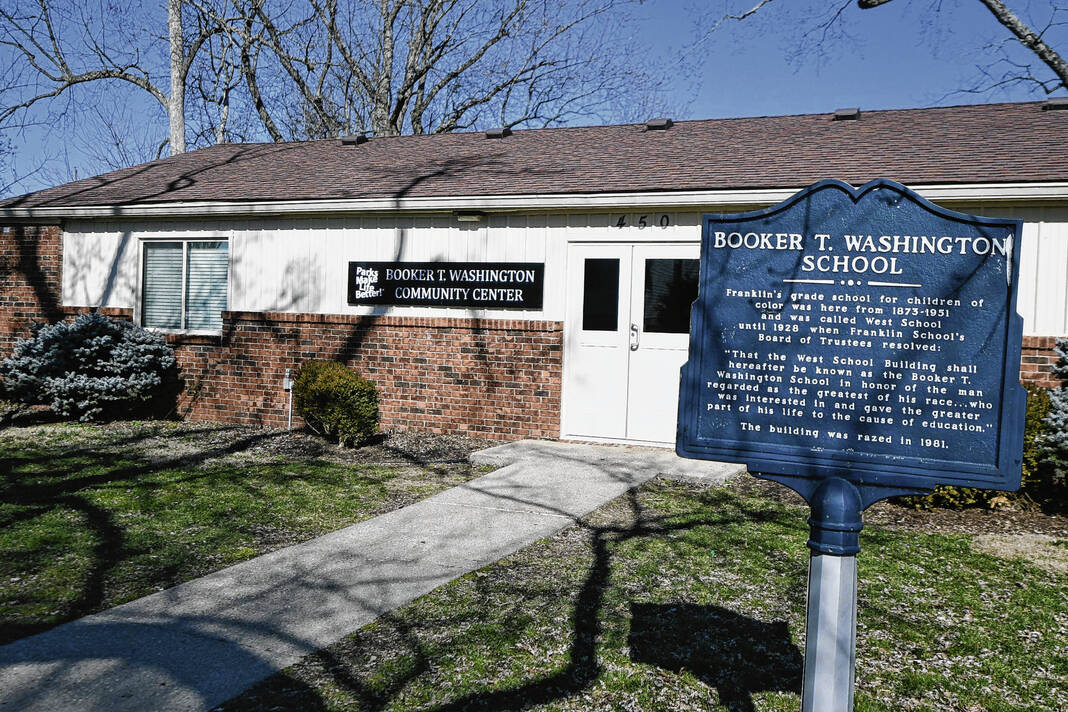

A community center named after the same man now stands in the footprint of the former Booker T. Washington School. The center and the school are named for an educator and activist who rose from slavery to become one of the most prominent Black leaders of the late 1800s and early 1900s. He is the founder of what is now called Tuskegee University in Alabama.

The school, located on Madison Street where Palmer Park is now, served students from 1873 to 1951 in what was a predominantly Black part of Franklin. McDuffey, however, lived closer to Franklin College growing up, and had to walk 30 minutes to school each day instead of attending the closer Payne Elementary School, which was limited to white students.

“We walked over here every morning. No one had cars except the school teacher and her car was not that big,” McDuffey said. “We didn’t pay that much attention to it because we were used to it.”

Unlike other places in Johnson County, Franklin had a large enough Black population to have a separate non-white school during segregation. Black students in other areas went to school with their white peers. Such was the case with Ray Crowe, who went to integrated schools in Whiteland and went on to coach the Crispus Attucks High School Boys’ Basketball team to the first state title for an all-Black school in U.S. history. Black Franklin students, however, attended school separately until high school, said David Pfeiffer, director of the Johnson County Museum of History.

The only other mention of an all-Black school in Johnson County historical records was the Colored School, which opened in Edinburgh in 1891 with a capacity of 50 students, according to “Follow the Drinking Gourd: History of African-Americans in Early Johnson County.” It is unclear when the school closed or how many students it served.

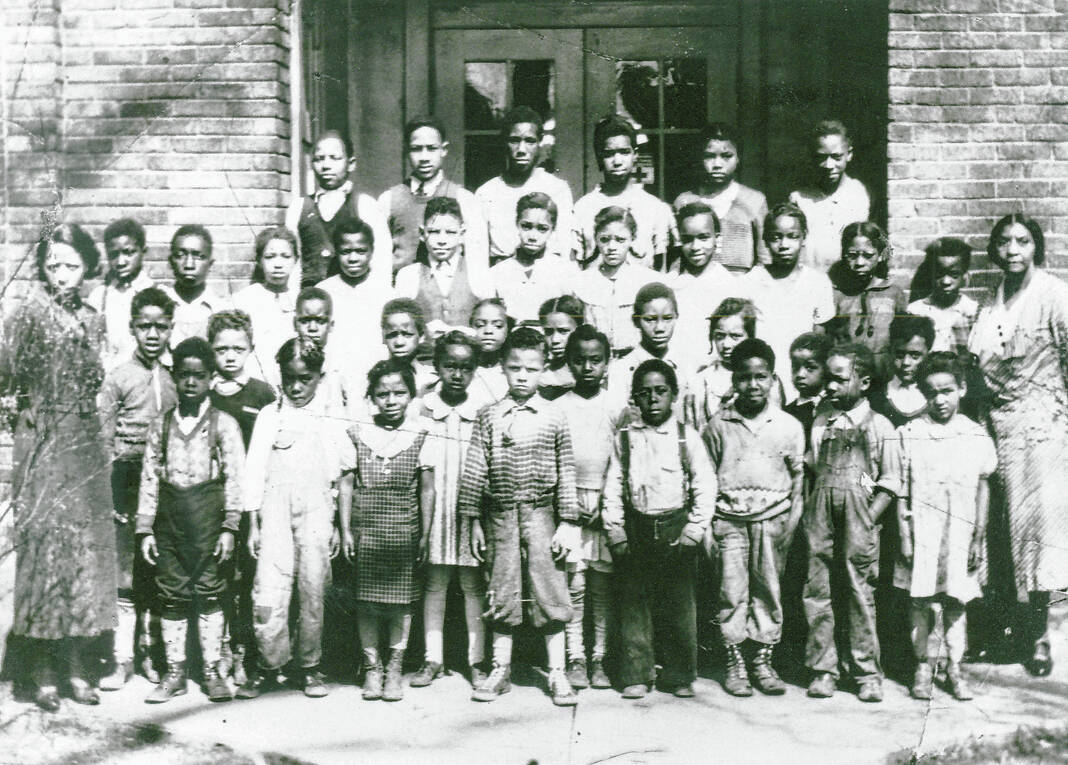

Booker T. Washington School, which served students in kindergarten through eighth grade, had two elementary school classrooms, one for music and art and one for core subjects. The school had about 40 students, and students from multiple grade levels would often be in the same classroom, separated by row based on grade. The school didn’t have a cafeteria and recess was outside, McDuffey said.

Pastor Douglas Gray, who preaches at the historically Black Second Baptist Church, looked into the school’s history because many of the families who attended his church had relatives who had gone to Booker T. Washington, which was known as the West School until 1928, Gray said.

“The school produced some great Americans to be honest with you,” he said. “The first African-American to graduate from Franklin College went there and was a member of Second Baptist, Dr. Arthur Henry Wilson.”

Wilson graduated from Franklin College in 1902 and found success as a physician. Other notable alumni include Ethel Harnett, a longtime teacher at the school who became its principal and Hattie Fossett-Caine, who served as Franklin’s first beautician, podiatrist and masseuse.

After McDuffey’s third grade year, Booker T. Washington School closed permanently and Franklin schools integrated. McDuffey went to Payne School, and despite racial tension during the Civil Rights Era, McDuffey said most of the discrimination she faced didn’t come from her classmates, but from policies in the city of Franklin itself.

“I didn’t have any issues at Payne School but within the city itself we weren’t allowed to go to the swimming pool. The (Artcraft) Theatre we could go to, but we had to sit upstairs,” McDuffey said. “There was a place that had deep water in it, and they would throw you in and you’d either sink or swim and that’s where most of us learned to swim.”

She also faced discrimination in high school, where a teacher called her a racial slur. Instead of the teacher facing discipline, however, administrators took McDuffey out of class, she said.

Although the high school was always integrated, it wasn’t rare for Black students to feel unwelcome there, especially during the first half of the 20th century, Gray said.

“I would assume they had some hardships, especially when the (Ku Klux) Klan was in its heyday in the 1910s and 1920s. They had a Klan gathering of over 2,000 people at the high school in the 1920s and I’m sure it bled off into other aspects of life,” he said.

As of 2022, Black students represented just 2.1% of the population at Franklin schools, according to data from the Indiana Department of Education. When Booker T. Washington School first opened 150 years ago, 5.3% of the school-age population was Black, Pfeiffer said.

Racial discrimination led to the exodus of what was once a significant Black population in Franklin, Gray said.

“As folks looked for opportunities elsewhere, it seemed there was a huge exodus,” Gray said. “They used to have Klan Day at the Johnson County Fair, and it caused some consternation. I think folks felt unsafe and just left.”

Economic disadvantages resulted in more of the Black population leaving Franklin even after the Klan lost prominence, McDuffey said.

“There were not many opportunities here because everything was so prejudiced. It was hard for them to buy a house,” she said. “The majority of them didn’t come back.”

But Booker T. Washington alumni, even if they may live far from Indiana, still want the school’s name to be preserved. Their efforts paid off in 2021, when the community center in Palmer Park where the school once stood was renamed the Booker T. Washington Community Center. The school itself was razed in 1981, but the building in its footprint will now forever carry the name of the prominent Black leader.

The park around it carries the name Palmer for Herriott Palmer, who left money in her will to fund a playground for children of color in Franklin. For McDuffey, who has lived just a block away from the site for the past 52 years, the name means more than just letters on a building.

“I’d like to see in continue to be preserved and keep the name. We’re just as important as everyone else,” McDuffey said. “That’s where all our relationships, friendships and our love for the community started—there in that school.”